Introduction to Inscribed Friendship

E·pí·gra·phy: the study and interpretation of ancient inscriptions; collectively, the inscriptions themselves

Chapter V moves us from the international to the interpersonal: the commemorations and statements of friendship by everyday people will be our focus. We will read touching remembrances of deceased friends and eternal vituperations of former friends. In the process we will encounter voices outside the world of elite male literary culture, reading descriptions of friends by women and men, free-born and freed, noble and nouveau rich, in Rome and the along the frontier.

First we will acquire a general sense of the ways that friendship appeared in Roman epigraphy. Then we will listen to stones that give voice to Roman woman and former slaves. Finally we will travel to Vindolanda, near the border of England and Scotland, where a bog has preserved thousands of artifacts that are normally lost to time, including incredible handwritten notes between local military leaders and their wives. Along the way we will learn how to read one of our most significant sources for information about Roman culture: the hundreds of thousands of inscriptions on stone, metal, and wood that comprise the world of Roman epigraphy.

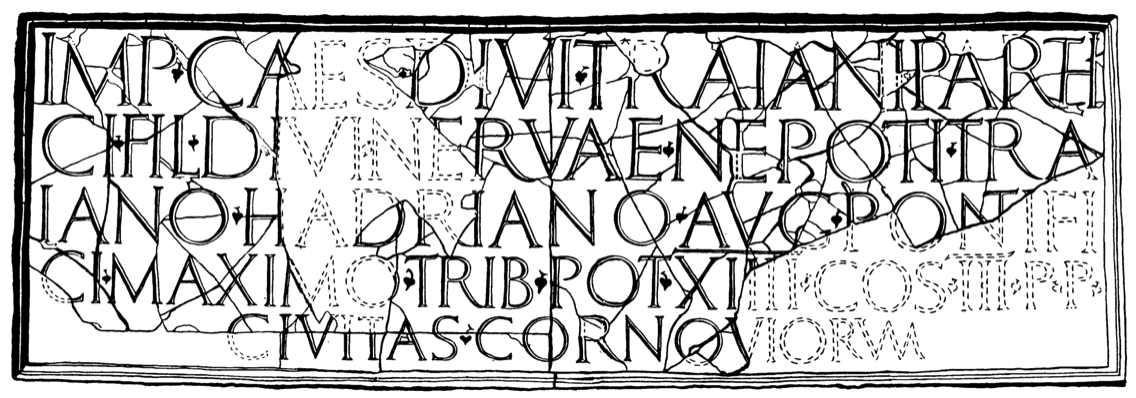

You will find that these inscriptions are presented in a variety of different ways. For some you will receive a transcription of the inscription. For others you will receive the text. For a few I have included a photograph or line-drawing of the inscription, and here the task of actually transcribing the inscription before creating a full text will be up to you. Some will have commentary; others questions. For others you will be on your own.

A Brief Introduction to Epigraphy

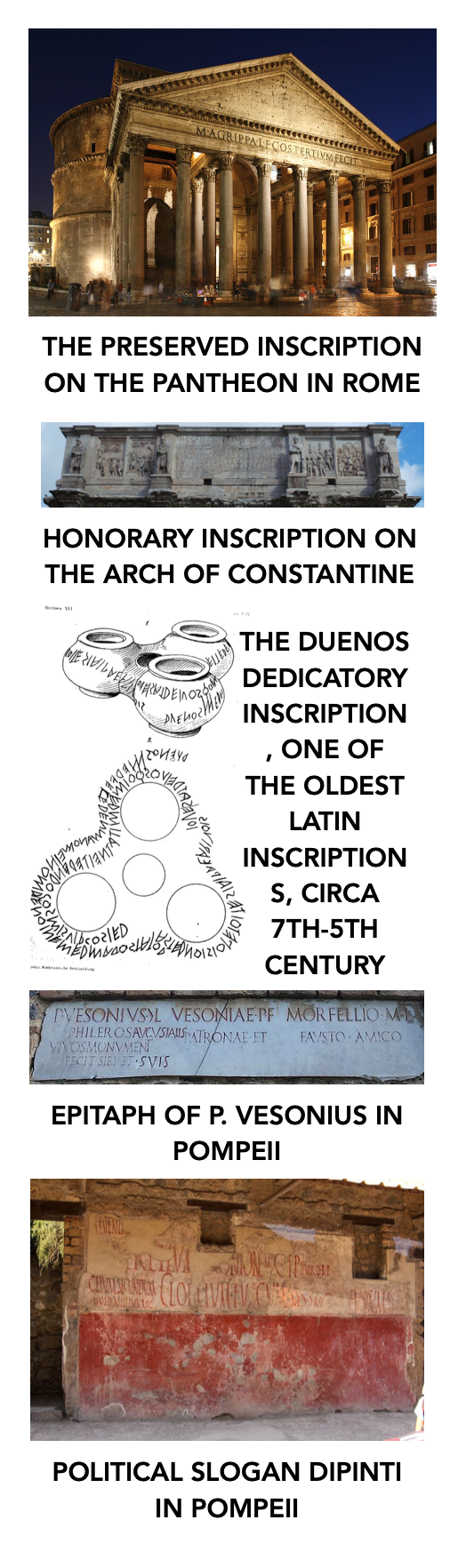

Epigraphy is the study of writing that has been inscribed (or in some cases, painted) on durable surfaces like stone, bronze, ceramic, wood, and other materials. Inscriptions from the ancient Roman world provide classicists with a wealth of information that we would not otherwise have about public and private life both in Rome itself, and in all the far-flung corners of the empire. Inscriptions are contemporary “witnesses” to people’s behaviors, beliefs, actions, and aspirations, and they generally fall into five main categories:

Building inscriptions record the construction (sometimes reconstruction) of temples, bridges, arches, and other public works. They usually record who was responsible for (or paid for) the work and to whom the building is dedicated.

Honorific inscriptions are usually found on statue bases or commemorative arches, and they honor the life and accomplishments of a particular individual. Also in this category one could include the inscriptions that bear town charters, treaties, and laws.

Dedicatory inscriptions occur on altars or other smaller objects that have been consecrated to the gods. Often they also contain information about the person making the dedication.

Epitaphs are the largest single category of inscriptions that we have from the Roman world. These can be found on tombstones, cinerary urns, or plaques on mausoleums for individuals or for families. These can simply have the name of the deceased and how long they lived, or they can record important life accomplishments or careers. Some even contain philosophical reflections on life and death (often in the form of short poems).

Graffiti and dipinti include all of the texts and pictures scratched (graffiti) or painted (dipinti) on walls or other surfaces. While the painted surfaces are closer to our notions of advertising or public announcements, the graffiti from the ancient world is very much in line with our own experience of graffiti—private musings on a variety of topics, often humorous and/or obscene.

Portable objects, like rings, necklaces, lamps, and jars also often contain simple inscriptions.

In this introductory module, most examples will be drawn from the honorific inscriptions and the epitaphs, since they are the most numerous and the ones most likely to be encountered “in the wild.”

Reading Inscriptions

Your first look at an inscription can be disheartening. The individual letters are often clear, but there is frequently no spacing between words and sentences, and it rarely seems like standard Latin prose. The language of the inscriptions is usually not very complicated grammatically—mostly simple declarative statements: “So-and-so made this [monument] for so-and-so.” Yet inscriptions can contain some forms and spellings that are either archaic or non-standard (meaning, not the spellings you have come to expect). Furthermore, the naming conventions and terms being used, especially some of the specialized political offices and occupations, may be unfamiliar to you.

To make things more complicated, since inscribing on hard surfaces, especially stone, is usually the work of a paid craftsman, and space is at a premium, inscriptions make frequent use of abbreviations (often only a single letter). Many of these will be easy to guess and reconstruct from context, since often they are the product of very regular formulas (like R.I.P— “Rest In Peace” or Requiescat In Pace — on a modern gravestone), but occasionally, some abbreviations are totally obscure, even to experienced epigraphers. You can find most abbreviations here. You will need to refer to these frequently at first.

You will also notice that most inscriptions are carved in “capital” letters. In fact, these letter-forms were generated especially for their use on hard surfaces, and so they tend to be more angular than the cursive letters you see regularly in print. One particular feature of Latin inscriptions to note is the use of the letter “V” for both the consonant “v” and the vowel “u.” You will quickly get used to this convention.

Since the middle of the 19th century, there has been an ongoing scholarly project to record all of the Latin inscriptions in one comprehensive collection. This is the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL), and it currently has over 300,000 inscriptions (and about 1,000 more are published each year)! You will see that almost all of our inscriptions carry an identifying CIL number, based on the part of the Roman world in which it was found and recorded. This makes consistent reference possible, and it simplifies the process of categorizing and cataloging new inscriptions as they are discovered.

Before we get to actual inscriptions, however, we need to become familiar with how the Romans named themselves because a large portion of any inscription is usually just the names of the people involved.

Transcription, text, and meaning

As I noted above, the basic grammar of most inscriptions is quite simple. Often, the inscription starts with a name in the dative case stating whom the inscription is “for.” Then there is usually another name in the nominative case stating who “made” (or caused to be made) the inscription. There can be additional elements identifying one or both figures, including their voting tribe, their place of origin, or their rank and/or occupation. Often the verb for making is understood, but sometime you will see it expressed—fecit, posuit, etc.). Remember, even though some obvious words are left out (or abbreviated), normal Latin grammar and syntax still control communication!

It is customary for epigraphers to reproduce in print, as precisely as possible, exactly what can be seen on the actual inscribed surface. This means using capital letters for the transcription (the actual letters of the inscription) with certain editing and punctuation marks deployed for clarity’s sake. Here are the most common:

(abc) Letters within parentheses were omitted by the stonecutter, but printed by the editors, often to fill out an abbreviation; e.g., F(ilius).

[abc] Letters within square brackets were inscribed but have been lost because of damage; the editor is certain that these missing letters can be restored; e.g., TREV[IR].

[ ] square brackets around a space show lost letters that cannot be restored; there may dots to show the number of missing letters.

< abc > Letters accidentally omitted on the stone; e.g., Augus < al > is.

[[abc]] Letters deliberately erased, as for example following damnatio memoriae: e.g., [[Domitianus]].

ạḅ Letters underdotted are doubtful because of damage or weathering; they cannot be restored with certainty.

For much more, see Keppie, Lawrence (2002). Understanding Roman Inscriptions.