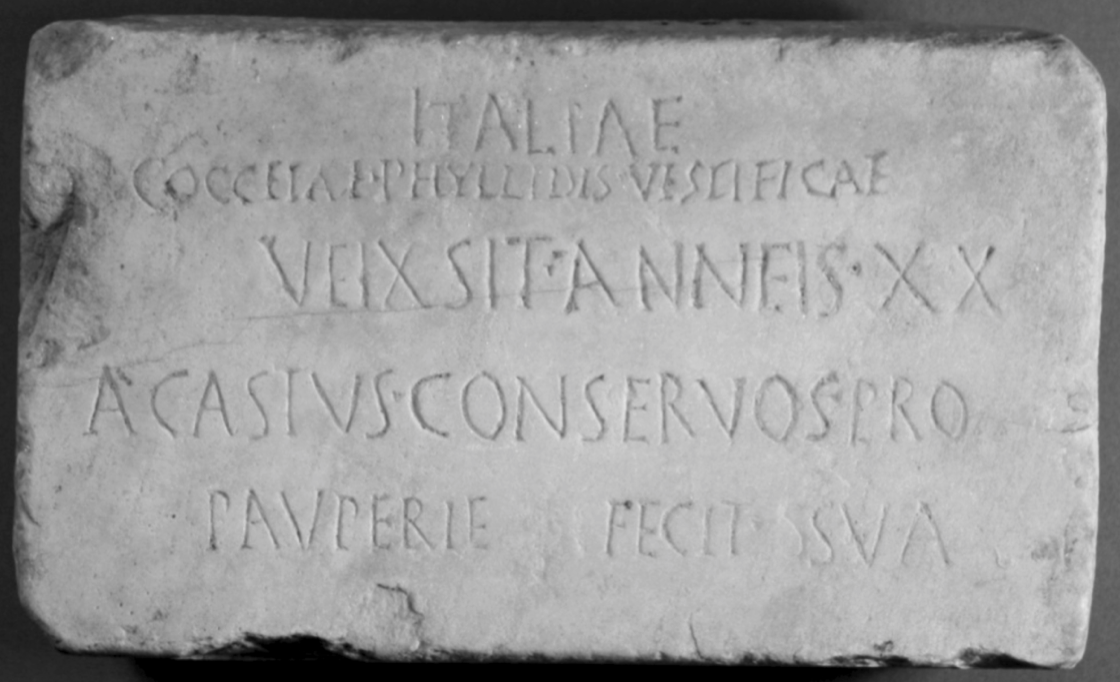

32 CIL 6.9980: Tombstone, Rome 2nd century CE

For your first foray into the world of epigraphy, I have included a short and simple example from a tombstone in Rome from the 2nd century CE (CIL 6.9980) as a “practice” sample to work through together.

First we transcribe exactly what we see and then create a full text of the inscription. In this case, these two will be identical (except for the capitals in the transcription) as there are no abbreviations in the practice inscription (although you will find some unorthodox spellings that we might regularize).

ITALIAE

COCCEIAE · PHYLLIDIS · VESTIFICAE

VEIXSIT · ANNEIS · XX

ACASIVS · CONSERVOS · PRO

PAVPERIE FECIT SVA

In the first line we read the inscription’s dedicatee, Italia, expressed in the dative since the inscription was dedicated to her.

The next line has a word that could be dative (Cocceiae) but the next word (Phyllidis) reveals that this word-group is genitive—and so likely refers to the owner of Italia. The final word of the second line (vestificae or “dressmaker”) offers some information about… Cocceia Phyllis? Italia? In a short inscription like this it is a safe bet that the first several lines will refer to the dedicatee. So vestificae is in the dative and agrees with Italiae: Italia was the dressmaker of Cocceia Phyllis, whose name suggests that she was a freedwoman of the emperor Nerva (who died in 98 ce).

In the third line we learn a piece of information common in funeral inscriptions, especially if the deceased passed away at a young age: Italia lived (veixsit = v{e}ixit = vīxit) for 20 (XX) years (anneis = ann{e}is = annīs in the ablative). In a more formal or elaborate inscription, this line might have included a relative pronoun (quae) but we can understand the sequence of thought well enough.

In line 4 we at last encounter a nominative: Acastus. Acastus was a fellow-slave (conservos = conservus) of Italia.

The end of line 4 and the final line reveal the reason that Acastus undertook the duty of burying Italia: he made the tomb (fecit) because of Italia’s poverty (pro I pauperie… sua).

So, if we were to write this inscription out as “normal”, edited Latin prose, we would see something like this: Italiae, Cocceiae Phyllidis vestificae, [quae] vixit annis XX, Acastus conservus pro pauperie fecit sua. Once you have had some practice reading more of these inscriptions, you will begin to get a feeling for what is being left out, and what is generally expected in the public and formal language of dedications. In the CIL (and in most publications) you will notice that all of the inscriptions are followed by an “official” text like this one, in which all of the abbreviations are spelled out in full.

As a general rule, inscriptions leave out what a native speaker could easily infer and supply. So, inscriptions will be a good test of your developing Latin intuition. But even if you cannot fully understand what each inscription actually “means,” create as much of the full text as possible as a foundation for tackling the inscription in class.