7. Lecsyony Gaz: Queity rgwezacdyëng Ingles “He doesn’t speak English well”

This lesson begins with questions (section §7.1). Subject proximal and distal pronouns are introduced in section §7.2, and sections §7.3 and §7.4 covers combination forms of verbs (to which these pronouns are attached) and their pronunciation. Free pronouns and their use as objects and focused subjects are described in section §7.5, and section §7.6 explains the use of free pronouns with cuan. Section §7.7 is a summary about pronoun use. Section §7.8 presents negative sentences.

Ra Dizh

a [àaa’] yes

bag [baag] cow

bar [baar] stick; pole

bdo [bdòo’] baby

budy [bu’uhuhdy] chicken

budy gwuar [bu’uhdy gwu’uar] turkey

budy ngual [bu’uhdy ngu’ahll] male turkey

clarinet [clarine’t] clarinet

chirmia [chirmia] traditional flute

e [èee] (used at the end of a question that can be answered with a “yes” or yac “no”; see lesson)

grabador [grabadoor] tape recorder

lai [la’ài’] he, she, it; him, her, it (distal; see lesson)

laëng [la’a-ëng] he, she, it; him, her, it (proximate; see lesson)

Lia Glory [Lia Gloory] Gloria

Mazh [Ma’azh] Tomas, Thomas

queity [que’ity] / quëity [quë’ity] not

rban [rbàa’an] follows a medical diet

rcuzh [rcuhzh] plays (a wind instrument)

rcwez [rcwèez] turns off (an appliance)

rcwual [rcwùa’ll] turns on (a radio, stereo, etc.)

rchiby [rchìiby] scares (someone)

rguch [rguhch] bathes (someone or something)

rgwezac [rgwèe’za’c] speaks (a language) well

Rony [Ro’ony] Jeronimo

rsubiaz [rsubihahz] dries (something)

rtyepy [rtyèe’py] whistles

ryac [rya’ahc] heals, gets well, gets better

rzhiby [rzhihby] gets scared

rzhiez [rzhìez] laughs; smiles

rrady [rraady] radio

telebisyony [telebisyoony] television

tu [tu] who

wbwan [wbwààa’n] thief

xa rni buny ra dizh [x:a rnnììi’ bùunny ra dìi’zh] pronunciation guide

xi [xi] what

yac [yaa’c] no

zhieb [zhi’eb] goat

zhily [zhi’ìilly] sheep

Lecsyony 7, Video 1. (With Ana López Curiel.)

Xiëru Zalo Ra Dizh

Turkeys are very important in Zapotec culture. In a small town like San Lucas Quiaviní, some turkeys are allowed to run free in the streets — and they know their way home. Budy ngual refers to a male turkey, while budy gwuar is more general term.

Fot Teiby xte Lecsyony Gaz. Chickens and a turkey in San Lucas Quiaviní.

§7.1. Two Types of Questions

Question word questions. Here are some Zapotec questions, sentences used to ask for information or confirmation:

|

Tu rcaz cha guet? |

“Who wants a tortilla?” |

|

Tu caban? |

“Who is following a medical diet?” |

|

Xi rcaz bdo? |

“What does the baby want?” |

|

Xi rcuzh Lia Petr? |

“What does Petra play?” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 2. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

These questions start with the tu “who” and xi “what”. like these always start with a question word (Zapotec speakers don’t use questions corresponding to English Petra plays what? with the question word later in the sentence). There are other question words as well, which you’ll learn in later lessons.

A-yac questions. Zapotec (like other languages) actually has two types of questions. Here are some examples of the second type:

|

Rcaz bdo cha guet e? |

“Does the baby want a tortilla?” |

|

Caban mes e? |

“Is the teacher following a medical diet?” |

|

Wbany mniny e? |

“Did the child wake up?” |

|

Rgwezac Jwany Dizhsa e? |

“Does Juan speak Zapotec well?” |

|

Rcuzh Lia Petr clarinet rata zhi e? |

“Does Petra play the clarinet every day?” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 3. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

Both types of questions ask for information, but while the first type needs an answer that could be a noun or name (like Bdo or Cha guet) or a sentence (like Bdo rcaz cha guet or Cha guet rcaz bdo), the second type only requires an answer like a [àaa’] “yes” or yac [yaa’c] “no”. The first type is a question word question; we can call the second an (in English, these are sometimes called yes-no questions!). As you can see, the way to ask a Zapotec a-yac question is to put the e [èee] at the end of the sentence that is used in the question.

The question marker e is pronounced with a rising tone (in a KPP pattern), which means that your voice goes up at the end of an a-yac question in a similar way to what happens with an English yes-no question. The rhythm of these questions is not exactly the same in English and Zapotec, though, so you should listen carefully to your teacher and try to make your e sound like theirs. Question word questions have a different rhythm, and do not use the question marker e. Try repeating both types of questions after your teacher.

Part Teiby. Translate the following question word questions into Zapotec. Then, listen as your teacher reads the correct translations, and make sure you can imitate the question rhythm.

a. Who wants a book?

b. Who did the bee sting?

c. What does the teacher play?

d. Who turned off the radio?

e. What scared Elena?

f. What is boiling?

Part Tyop. Translate each of the following a-yac questions into Zapotec. Then, listen as your teacher reads the correct translations, and make sure you can imitate the question rhythm.

a. Did Gloria give a pencil to the teacher?

b. Is the cow running?

c. Does the girl remember Elena?

d. Did Pedro teach Juan Zapotec?

e. Is the bell ringing now?

f. Does Juan whistle every day?

Focus and question word questions. Look at the following question-word questions and answers:

|

Tu rcaz cha guet? — Bdo rcaz cha guet. |

“Who wants a tortilla?” — “The baby wants a tortilla.” |

|

Xi rcaz bdo? — Cha guet rcaz bdo. |

“What does the baby want?” — “The baby wants a tortilla.” |

|

Tu bcwual rrady? — Lia Len bcwual rrady. |

“Who turned on the radio?” — “Elena turned on the radio.” |

|

Xi bcwual Lia Len? — Rrady bcwual Lia Len. |

“What did Elena turn on?” — “Elena turned on the radio.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 4. (With Anda and Geraldina López Curiel.)

As these pairs show, if you use a complete sentence to answer a question word question, the new information is usually focused. (In Zapotec, complete sentence answers are probably more common than they are in English.) In other words, just as the question word comes at the beginning of the question, the information that replaces it (bdo replacing tu, cha guet replacing xi, and so on) is focused, in the same position. (If you read the English question and answer pairs above aloud, you’ll hear focus emphasis on the underlined words in the answers, just as discussed in Lecsyony Gai.)

Focus in a-yac questions. A-yac questions work differently. It is less common to focus words in Zapotec a-yac questions than in ordinary sentences, and when words are focused in questions they are strongly emphatic. However, you will hear sometimes speakers use questions like:

|

Jwany rgwezac Dizhsa e? |

“Does Juan speak Zapotec well?” |

|

Dizhsa rgwezac Jwany e? |

“Does Juan speak Zapotec well?” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 5. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

Answers to questions like these don’t always involve focus. So the following could be a “yes” answer to both of the focus questions.

|

A, rgwezac Jwany Dizhsa. |

“Yes, Juan speaks Zapotec well.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 6. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

Adverbs like na, nai, and rata zhi (an adverb phrase) can also be focused in a-yac questions:

|

Na rcyetlaz mniny e? |

“Is the child happy now?” |

|

Rata zhi rcuzh Lia Petr clarinet e? |

“Does Petra play the clarinet every day?” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 7. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

Because this is a very common sentence position for adverbs, adverbs at the beginning of a sentence are not necessarily strongly emphasized.

Part Teiby. Write full sentence answers to each of the question word questions in Tarea Teiby, Part Teiby. Then work with another student to practice these mini-dialogues.

Part Tyop. Write full sentence a “yes” answers each of the a-yac questions in Tarea Teiby, Part Tyop. (You’ll learn later in this lesson how you could have answered these questions with negative sentences.) Then work with another student to practice these mini-dialogues.

Part Chon. Rewrite the questions in Tarea Teiby, Part Tyop with the nouns, names, or adverbs given below focused, as in the example. Then work with another student to practice mini-dialogues with these questions and the “yes” answers from Part Tyop above.

Example. a. “a pencil”

Answer. Teiby lapy bdeidy Lia Glory mes e? — Bdeidy Lia Glory lapy mes.

b. “the cow”

c. “Elena”

d. “Zapotec”

e. “now”

f. “Juan”

§7.2. Verbs with proximate and distal pronoun subjects

Words like English I, me, you, he, him, she, her, and it are — they serve the same function as noun phrases (nouns, names, or longer phrases) in sentences (as subjects or objects), but either refer to participants in the conversation (I and me refer to the speaker, you to the hearer) or are used to refer to other people or items that can be identified by those participants.

In Zapotec, pronoun subjects are not separate words (as in English), but are attached as endings added to the verb stem. Here are some examples:

|

Cazhunyëng. |

“He (this one) is running.”, “She (this one) is running.” |

|

Cazhunyi. |

“He (that one) is running.”, “She (that one) is running.” |

|

Mnazëng budy gwuar. |

“He (this one) grabbed the turkey.”, “She (this one) grabbed the turkey.”, |

|

Mnazi budy gwuar. |

“He (that one) grabbed the turkey.” “She (that one) grabbed the turkey.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 8. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

-Ëng ([ëng]) is a (“prox.”) pronoun and -i ([ih]) a (“dist.”) pronoun. Choose the proximate if you are referring to someone or something close by and easily visible. Use the distal if you are referring to someone or something farther away or out of sight. These pronouns are , because they must always be attached to something, such as the verbs in these examples. (Noun phrases containing re also make reference to the location of something relative to the speaker. However, unlike re phrases, the -ëng and -i pronouns are not emphatic or even strongly contrastive.)

As you can see from the examples, these Zapotec pronouns may be used to refer to both males and females, primarily people who are contemporaries or equals of the speaker. They can be translated with either English “he” or “she”. These Zapotec pronouns are (able to refer to any gender), and some people might translate them using “they (sg.)”, as in the following example. (While we won’t translate singular pronouns with “they (sg.)” in this book, you should feel free to do so in your homework.)

|

Rnyityi. |

“They (sg.) are missing.” “He is missing.” “She is missing.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 9. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

The proximate and distal pronouns may also be used to refer to people you don’t know at all or who are not important to you. They can also refer to certain (non-living) items, as in

|

Rnyityi. |

“It (that one) is missing.”, “It is lost.” |

|

Rnyityëng. |

“It (this one) is missing.”, “It is lost.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 10. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

The “it” in these examples could be a book, a pen, or money, for example.

When you listen to your teacher, other speakers, or the people on the recordings, you’ll probably notice that when -i is added to words that end in y (like cazhuny in the examples) the y is not easy to hear. The combination of yi at the end of a Zapotec word often sounds pretty much like just i.

When you add -i or -ëng pronoun onto a verb that ends in the letter c, there is a spelling change:

|

Byaqui. |

“He (that one) got better.” |

|

Ryaquëng. |

“She (this one) gets better.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 11. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

The habitual stem of “gets better” is ryac, and the normal perfective stem is byac. However, c always is written as qu before i and ë (as explained in Lecsyony Tyop), so when you use an -i or -ëng subject for any form of this verb (or any other verb ending in c), the verb must be spelled with a qu. There’s no pronunciation change here — both c and qu are pronounced just the same in Zapotec. (The same spelling change happens with any pronoun or other verb ending beginning with i, ë, or e.)

The pronouns -i and -ëng are pronouns — they are only used to refer to one individual. You’ll learn pronouns (used to refer to more than one individual) later. Zapotec pronoun usage is complicated. You’ll be learning more about this over the course of the next few lessons. Do not use proximate and distal pronouns to refer to highly respected people. These pronouns can be used to refer to children and animals, though there is another pronoun that can be used here as well. Most speakers also would not use proximate and distal pronouns to refer to water or tortillas, so you should not do this either. You’ll learn about how to use pronouns to refer to all of these people and items later.

Remember, all the Zapotec subject pronouns that you’ll learn must be attached to the verb of their sentence. They are not separate words, and they cannot appear in other positions in the sentence the way nouns can.

Part Teiby. Translate the following sentences and questions into Zapotec. Practice saying each one out loud.

a. He (that one) turned off the radio and the television.

b. She (this one) turned on the tape recorder.

c. Did she (that one) laugh?

d. It (this one) is scaring the male turkey.

e. He (that one) speaks Spanish well.

f. She (this one) rode a horse.

g. It (that one) is really ringing.

h. He (this one) is missing money.

i. She (that one) hit this cat.

j. He (this one) left a book and a C.D. behind.

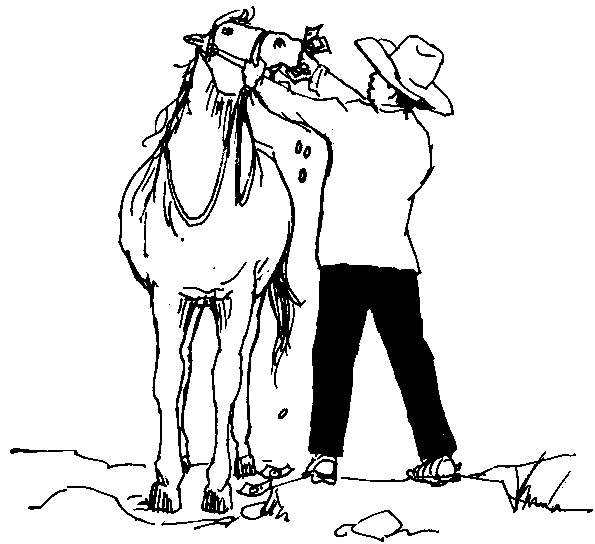

Part Tyop. Create a Zapotec sentence for each of the pictures below using either a proximate or distal pronoun. Then translate your sentence into English.

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

§7.3. Combination forms of verbs

If you compare any of the verbs with -ëng or -i pronoun subjects in section §7.1 with the normal habitual, perfective, or progressive forms of those verbs that you learned in Lecsyony Gai and Lecsyony Xop, you should not hear any difference between the verb used on its own (in its form) and the verb with the added pronoun subject. Verb bases with CB, KC, KCP, and KP (the pattern of vowels in their key syllable, the last syllable of the independent form), for example, don’t change their pronunciation when pronoun subjects are attached. (If you’ve forgotten how to interpret a xa rni buny ra dizh “pronunciation guide” or what abbreviations like CB and KKC mean, you should review these concepts in Unida Teiby.)

We can refer to the form of a verb base that is used before a pronoun or other ending as that base’s form. The combination form of the verbs in the examples in section §7.1 is the same as their independent form, but the pronunciation of other verbs changes in the combination form. Whether there’s a change depends on the vowel pattern of the verb base. Listen as your teacher pronounces these examples of verbs that change in the combination form:

|

Ryulaz buny mna. |

“The man likes the woman.” |

|

Ryulazëng mna. |

“He (this one) likes the woman.” |

|

Ryulazi mna. |

“He (that one) likes the woman.” |

|

|

|

|

Bseidy Jwany Dizhsa. |

“Juan learned Zapotec.” |

|

Bseidyëng Dizhsa. |

“He (this one) learned Zapotec.” |

|

Bseidyi Dizhsa. |

“He (that one) learned Zapotec.” |

|

|

|

|

Casudieby mna nyis. |

“The woman is boiling water.” |

|

Casudiebyëng nyis. |

“She (this one) is boiling water.” |

|

Casudiebyi nyis. |

“She (that one) is boiling water.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 12. (With Ana López Curiel.)

If you listen, you’ll hear that these verbs sound different when the pronoun subjects -ëng and -i are added. The verbs here have KKC vowel patterns ([ryu’lààa’z], [bsèèi’dy], and [casudììe’by]) in their independent form. (Recall that the vowel pattern is what you hear in the last syllable of the verb base.) Verbs like these whose base has a KKC vowel pattern change their vowel pattern to KC ([ryu’làa’z], [bsèi’dy], and [casudìe’by]) in the combination form.

Here is how it works. In the KKC verb base yulaz [yu’lààa’z], all the vowels of the pronunciation guide for the last syllable are the same, so it’s easy to change this to a KC pattern [yu’làa’z]. The KKC verb bases seidy and sudieby, however, have diphthongs in their last syllable ([sèèi’dy] and [sudììe’by]). In the combination form of a verb base containing a diphthong, the first element of the diphthong is represented by the first part of the combination form, and the second element by the second part. The diphthong in the verb base “learn” is ei, so the e must be a K vowel and the i must be a C vowel; in “boil”, the diphthong is ie, so the i must be a K vowel and the e must be a C vowel: the combination forms of these verbs are pronounced [sèi’dy] and [sudìe’by].

Rsubiaz “dries” is another example of a verb whose combination form is different from its independent form. The independent form of this verb has a BB vowel pattern ([subihahz]); in the combination form, this becomes a PB pattern ([subiahz]).

Part Teiby. Rewrite each of the following sentences by replacing the noun subjects with pronoun subjects. Then translate your new sentences into English. Most of the sentences with pronoun subjects could have additional different translations. Can you see what these would be?

a. Rtyepy mna e?

b. Caguch buny bdo.

c. Zhyap bchiby wbwan.

d. Mnaz mes guet.

e. Candieby nyis e?

f. Dizhsa bseidy mes mniny.

Part Tyop. Compare the verbs of the original sentences in Part Teiby and the sentences you wrote with pronoun subjects, which use combination forms. Practice saying each sentence both in the original form and with the pronoun subject. The pronunciation of some verbs will change in the combination form when the pronoun subject is added. Make sure your teacher feels you can pronounce all the verbs correctly.

Below is a chart of independent and combination forms for the verb types you’ve worked with so far in these lessons. These are all verb bases that end in one or more consonants. The chart shows the vowel type for both the independent and the combination forms. Verbs above the shaded row in the chart do not change their pronunciation in the combination form. Verbs below the shaded row do change their pronunciation in the combination form. Each verb is given with a “He…” example using -i. (Sentences that need an object to be complete end in “…” in the chart.)

| Independent and Combination Forms of Valley Zapotec Verb Bases Ending in Consonants | ||||

| Independent Form | Combination Form | Example with -i | ||

| Vowel Pattern | Habitual (independent) | Vowel Pattern | Habitual (combination) | |

| KC | rzhuny [rzh:ùu’nny] | KC | rzhuny [rzh:ùu’nny] | Rzhunyi. “He (that one) runs.” |

| KCP | rnaz [rnàa’az] | KCP | rnaz [rnàa’az] | Rnazi… “He (that one) grabs…” |

| KP | rguad [rgùad] | KP | rguad [rgùad] | Rguadi… “He (that one) pokes…” |

| CB | rduax [rdu’ahx] | CB | rduax [rdu’ahx] | Rduaxi. “He (that one) barks.” |

| B | rbany [rbahnny] | B | rbany [rbahnny] | Rbahnnyi. “He (that one) wakes up.” |

| CP | rxyeily [rxye’illy] | CP | rxyeily [rxye’illy] | Rxyeilyi… “He (that one) opens….” |

| KKC | rseidy [rsèèi’dy] | KC | rseidy [rsèi’dy] | Rseidyi… “He (that one) teaches…” |

| BB | rsubiaz [rsubihahz] | PB | rsubiaz [rsubiahz] | Rsubiazi… “He (that one) dries…” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 13. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

§7.4 More about pronunciation of verbs with pronoun subjects

In addition to combination form changes, some verbs have other pronunciation changes that vary according to what element is attached. Compare the verbs of the following three sentences:

|

Wbany Rony. |

“Jeronimo woke up.” |

|

Wbanyi |

“He (that one) woke up.” |

|

Wbanyëng |

“He (this one) woke up.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 14. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

Listen carefully as your teacher says each sentence, paying special attention to the bany base of each verb. Wbany [wbahnny] and wbanyi [wbahnnyih] have similar vowel patterns (each verb’s key syllable contains a B breathy vowel, with a low tone), since the combination form of a verb with a B vowel pattern in its independent form is unchanged. On the other hand, the base of wbanyëng [wbàa’nyëng] has a different vowel pattern (a KC combination, with a falling tone).

The distal pronoun -i can be added to the combination form of any verb whose base ends in a consonant with no other pronunciation change. Some verbs, however, change their pronunciations when -ëng is added. Rbany is one verb of this type.

You’ll learn more about combination forms and other changes in verbs with pronoun subjects in later lessons.

Part Teiby. Translate the following sentences into Zapotec. Read each of your Zapotec sentences out loud.

a. He (this one) woke up a cat.

b. Did it (that one) boil?

c. She (that one) gave the teacher a book and a pencil.

d. She (this one) really got scared.

e. Does he (that one) like the dog?

f. He (this one) plays the clarinet and the flute.

Part Tyop. Rewrite each sentence from Tarea Gai, Part Teiby, with a subject noun phrase (not a pronoun). Translate your new Zapotec sentence into English. Practice reading your new sentences aloud, paying attention to whether the verb base is pronounced the same in the new sentence, or whether a combination form is used.

From now on, we will not always specify “this one” and “that one” in translations for the proximate and distal pronouns. For instance, we could translate the last two sentences above as

|

Wbanyi. |

“He woke up.” |

|

Wbanyëng. |

“She woke up.” |

or as

|

Wbanyi. |

“She woke up.” |

|

Wbanyëng. |

“He woke up.” |

There is no association between either the proximate pronoun or the distal pronoun and a particular choice of “he” or “she”. Remember to choose the pronoun that is appropriate in a given context, according to the distance and visibility of the person or item referred to.

Complete the chart below, filling in the missing items in the first three columns as in the example. Then, make up an appropriate example sentence with a pronoun subject to illustrate each habitual and perfective verb. Give a translation for each sentence. Finally, read all your example sentences out loud, making sure to pronounce the verbs in their combination form.

| Habitual Stem | English meaning | Perfective Stem | Habitual example (with pronoun subject) | Perfective example (with pronoun subject |

| Ex. rseidy | teaches | bseidy | Rseidyi mniny Dizhsa. | Bseidyëng Lia Len Ingles. |

| a. rchiby | ||||

| b. | remembers | |||

| c. rcwez | ||||

| d. | mnab | |||

| e. | wakes up | |||

| f. rcwual | ||||

| g. | bcuzh | |||

| h. | whistles | |||

| i. | bzhiby | |||

| j. | jumps | |||

| k. rzhiez | ||||

| l. | opens (something) | |||

| m. ryac | ||||

| n. rguch |

§7.5. Free pronouns

As you’ve seen, “he”, “she” and “it” proximate and distal subjects must be attached to a verb. Here are some examples of sentences with “him”, “her”, and “it” objects:

|

Bguad mniny bar lai. |

“The boy poked a stick at him.” |

|

Cacwanyi laëng. |

“He is waking her up.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 15. (With Ana López Curiel.)

The pronouns lai ([la’ài’]) and laëng ([la’a-ëng]) are the distal and proximate FREE pronouns. Unlike bound pronouns, free pronouns do not have to be attached to another word. Free pronouns can be used as objects, as in the above sentences, in the normal position for objects, following the subject of the sentence (either a noun phrase or a bound pronoun). (Laëng has a hyphen in its pronunciation guide, indicating that this word has two syllables, as explained in §4.2. Listen carefully as your teacher says it. It may sound like one syllable to you (the ë is hard to hear!), but if you contrast it with other words with the CP pattern, you’ll hear the difference.)

Another way to use free pronouns is when you want to focus a pronoun subject, as in the following examples:

|

Laëng bguadëng bar mes. |

“She poked a stick at the teacher.” |

|

Lai cacwanyi zhyap.** |

“He is waking up the girl.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 16. (With Ana López Curiel.)

These sentences are different from the focus sentences you’ve seen up to now. When a pronoun subject is focused, the sentence must contain not only the focused free pronoun at the beginning of the sentence, but also the bound pronoun subject attached to the verb. You can never begin a sentence with a focused free pronoun subject without including a bound subject pronoun attached to the verb.

A good way to think of how this works is to remember that any verb with a pronoun subject must have a bound pronoun attached to it. Free pronouns are never used after verbs to indicate subjects. The bound pronoun attached to the verb is what tells you what the subject is. Adding a focused version of the pronoun at the beginning of the sentence is extra. A free pronoun can never be the only indicator of the subject of a sentence that contains a verb.

As the examples here show, free pronouns may be translated as either subjects or objects — “he”, “him”, “she”, “her”, and “it” are all good translations for these pronouns.

Free pronoun objects cannot be focused. When the object of a sentence is a pronoun, it must come after the subject (or after the verb, if the subject is focused).

Fot Tyop xte Lecsyony Gaz. Goats in San Miguel del Valle.

Complete the following sentences so that each includes at least one pronoun (bound or free; some sentences already include pronouns). Then translate your sentences into English.

a. Bcuzhi teiby .

b. Lai catyis .

c. Uas rchiby zhieb .

d. Teiby mnabëng.

e. Caguch .

f. Ryulaz mes.

g. Btyepy .

h. Teiby cabai wbeb .

i. Cataz zhily.

j. Lia Glory bcwual .

§7.6. Using pronouns with cuan

Free pronouns are also used following cuan “with, and”. Here are some examples:

|

Catyis mniny cuan laëng. |

“The boy is jumping with her.” |

|

Bdeidy zhyap liebr lai cuan mes. |

“The girl gave him the book with the teacher” |

|

Zhyap re cuan lai bdeidy liebr mes. |

“This girl and he (he and this girl) gave the teacher the book.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 17. (With Ana López Curiel.)

(Just as in English, these sentences may sound a little strange out of context — people hearing this want to know who the “her”, “him”, and “he” are that you are referring to!)

In sentences like these, the pronoun used after cuan is a free pronoun. (Some people might refer to the noun or pronoun following cuan as the object of cuan.)

Translate the following sentences into Zapotec. Practice saying each one out loud.

a. The teacher and she really speak English and Zapotec well.

b. That boy and that girl got scared.

c. Pedro scared the goat with her.

d. The teacher and he boiled the water.

e. The boy and she are asking for a tortilla.

§7.7. Summary: Types of pronouns

In this lesson, you’ve learned two types of pronouns, bound pronouns (always attached as endings on the word that comes before them in the sentence) and free pronouns (separate words).

Bound pronouns can be used as subjects of verbs and in other ways you’ll learn about later. You might wonder why we don’t call them subject pronouns, but in fact they do have other uses, and there is one bound pronoun you’ll learn about later that can’t be used as a subject. In this lesson, you’ve seen bound pronouns only attached to the verb of the sentence. Bound pronouns must be attached to some other word; they can’t be pronounced on their own.

Free pronouns, which are separate words that speakers can say on their own, can be used in a number of ways: as objects, as focused subjects, with cuan, and in other ways you’ll learn about later. The main thing to remember is that in sentences with a verb a free pronoun can never be the main subject — it may be a focused subject, but in that case there must always be a bound pronoun subject following the verb as well.

§7.8. Negative sentences

The negative sentence pattern. The Zapotec word queity [que’ity] “not” is used to mean “not” in sentences like

|

Queity bzhyunydi mniny. |

“The boy didn’t run.” |

|

Queity caduaxdi becw. |

“The dog isn’t barking.” |

|

Queity rgyandi Bed budy. |

“Pedro doesn’t feed the chicken.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 18. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

A Valley Zapotec sentence starts with queity (some speakers say quëity [quë’ity]). Next comes the verb. After the verb, before the subject, comes a special ending -di [di’], which is used to complete certain types of negative sentences. -Di is a , a special type of ending that is not a pronoun. Particles are endings that come after a verb stem, but before a pronoun, if there is one.

When there is a pronoun subject ending, that ending comes after the negative particle -di on the verb. Before a pronoun that begins with a vowel, -di becomes -dy [dy].

|

Queity bdeidydyi liebr mes. |

“He didn’t give the book to the teacher.” |

|

Queity rgwezacdyëng Dizhtily. |

“He doesn’t speak Spanish well.” |

|

Queity catyisdyëng. |

“She isn’t jumping.” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 19. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

(Both subject pronouns that you’ve learned in this lesson, -ëng and -i, start with vowels, so you will always use -dy before these pronoun subjects. However, some other pronouns start with consonants, as you will see later.) If you listen to the pronunciation of verbs like bdeidy that change in the combination form before -di, you’ll hear that the combination form is used before -di, as before any ending. Here’s the new pattern:

| queity | verb (comb. form) |

-di | subject | (rest of sentence) |

| Queity | bzhyuny | -di | mniny. | |

| Queity | caduax | -di | becw. | |

| Queity | rgyan | -di | Bed | zhyet. |

| Queity | rdeidy | -dy | -i | liebr mes. |

| Queity | rgwezac | -dy | -ëng | Dizhtily. |

| Queity | catyis |

-dy | -ëng. |

In the diagram, hyphens appear between verbs and -di and also between -di and bound subject pronouns, just so that the columns will line up.

Negative questions. Questions usually use a different negative sentence pattern, as you can see in the following examples:

|

Queity rgyan Rony budy e? |

“Doesn’t Jeronimo feed the chicken?” |

|

Queity catyisëng e? |

“Isn’t she jumping?” |

Lecsyony 7, Video 20. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

As these examples show, the -di ending is usually not used on the verbs in questions. The pattern is

| queity | verb (comb. form) |

subject | (rest of sentence) |

| Queity | rgyan | Rony | budy e? |

| Queity | catyis | -ëng | e? |

(You may hear some speakers using -di somewhat differently in certain types of sentences. Listen carefully, and notice what your teacher says!)

Translate each of the following sentences into Zapotec. Practice saying each sentence out loud, paying special attention to the combination form of the verb.

a. The bell isn’t ringing now.

b. Isn’t she getting better?

c. He doesn’t smile.

d. She doesn’t remember the teacher.

e. Didn’t the cat wake Tomas up?

Negative sentences with a copied subject. You cannot focus a noun phrase or pronoun in a negative sentence using the normal focus patterns you’ve learned in this unit. However, sometimes speakers will begin a negative sentence with a copy of the subject noun phrase or pronoun, as follows:

|

Mniny queity bzhunydi mniny. |

|

Becw re queity catyisdi becw re. |

|

Laëng queity catyisëng e? |

Lecsyony 7, Video 21. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

As the second example shows, this works even if the subject noun phrase includes re. Another way to do the same thing is to use a noun phrase at the beginning of the sentence, but a pronoun (referring to the same individual) for the subject after the verb, as in

|

Bed queity rgwezacdyëng Ingles. |

|

Mes re queity caseidydyi Dizhsa. |

Lecsyony 7, Video 22. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

These sentences are something like English sentences like “The boy, he didn’t run”, “As for him, is he jumping?”, “That teacher, he’s not teaching Zapotec”, or “Pedro, he doesn’t speak English well” — but not exactly.

This kind of sentence is more common in Zapotec than in English, so it’s useful to practice using it.

Rewrite each sentence you came up with in Tarea Ga so that it begins with a copy of the subject. Read the new sentences aloud.

Prefixes, Endings, and Particles

-ëng [ëng] he, she, it (proximate singular bound pronoun)

-i [ih] he, she, it (distal singular bound pronoun)

-di [di’] (negative particle)

-dy [dy] (form of -di used before bound pronouns beginning with vowels

Abbreviations

dist. distal

prox. proximate

Comparative note. The area where there may be most grammatical variation among the Valley Zapotec languages is in pronoun usage. Speakers notice and comment on these differences, but they do not seriously impede communication in most cases. Not all languages have proximate and distal pronouns, and other languages have different pronouns that we will not introduce in this course. At the end of this book is a comparative table of the different pronouns used in several Valley Zapotec languages. If you know speakers of other varieties of Valley Zapotec, you will learn other pronoun systems.

A word that comes at the beginning of a question that asks for specific information, such as "who", "what", "when", or "why".

A question that begins with a QUESTION WORD, and asks for specific information, not just a "yes" or "no" answer.

A question that can be answered with a or yac.

A word that comes at the end of a question to show that the SENTENCE is a question.

A word that serves the same function as a NOUN or NOUN PHRASE in a SENTENCE (as a SUBJECT or OBJECT), but that refers either to participants in the conversation (I and me refer to the speaker, you to the hearer) or to other people or items that can be identified by those participants without their names being mentioned. Examples of pronouns in English are I, me, you, he, him, she, her, and it. All Zapotec pronouns have both BOUND and FREE forms. See also A-PRONOUN, ANIMAL PRONOUN, DISTAL PRONOUN, FAMILIAR PRONOUN, PROXIMATE PRONOUN, RESPECTFUL PRONOUN, REVERENTIAL PRONOUN.

A PRONOUN used to refer to someone or something close by and easily visible; abbreviated as "prox.".

A PRONOUN used to refer to someone or something relatively far away or out of sight; abbreviated as "dist.".

Attached. An element that is bound must always be attached to some other word. Bound PRONOUNS are different from FREE pronouns, which do not have to be attached.

Able to refer to any gender. Unlike English singular

PRONOUNS, which are specified as masculine (for instance, "he"),

feminine ("she"), or inanimate ("it"), Valley Zapotec pronouns are

gender neutral.

Non-living (referring to an item that is not an animal or human being).

Referring to just one item or person.

Referring to more than one item or person.

The simplest form of a word, without any added ENDINGS. It refers to the way the word is pronounced on its own, without any of the changes you might hear if it was used in a SENTENCE. The words listed in the Rata Ra Dizh are in the independent form. When endings are added to a word, they must be added to its COMBINATION FORM.

The pattern of VOWEL types in the KEY SYLLABLE of a word. Vowel patterns are written as a sequence of the abbreviations for the VOWEL types in the word, using P for PLAIN VOWELS, C for CHECKED VOWELS, K for CREAKY VOWELS, and B for BREATHY VOWELS.

The form of a word that is used before a PRONOUN or other ENDING. It is often shorter than a word's INDEPENDENT FORM.

Referring to a SENTENCE that is used to deny the truth of the corresponding non-negative sentence.

A special type of ENDING that is not a PRONOUN. Particles are endings that come after a VERB (or other) STEM, but before a pronoun, if there is one.