18. Lecsyony Tseinyabchon: Tyop buny cagwi lo ra budy “Two people are looking at chickens”

Fot Teiby xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon. Tyop buny cagwi lo ra budy.

Ra Dizh

a [a] (word used before focused subjects in locational sentences; see section §18.4)

botei [bote’i] bottle

cwe [cwe’eh] beside, next to

dets [dehts] behind, in back of

guecy [gue’ehcy] / guëcy [guë’ëhcy] above; on top of, at the very top of

lany [làa’any] 1. in; 2. into

lo [loh] 1. on; 2. in front of; 3. to

ni [ni’ih] under

par [pahr] for

ran [ràann] looks after, takes care of (someone; a church or shrine) § perf. mna [mnàa], irr. gan [gàann]

ran lo [ràann loh] sees (something) > ran “sees”

ratga [ràa’tga’ah] lies down (in a location) (CB verb) § perf. guatga [gùa’tga’ah]; irr gatga; neut. natga

rbe permisy lo [rbee’eh permi’sy loh] asks permission from (someone) > rbe

rbeb [rbèe’b] gets (put) into a position (on a flat, elevated surface); is (habitually) in a position (on a flat, elevated surface) § neut. beb

rbecy lo [rbèe’cy loh] fights (a bull) > rbecy

rbeluzh [rbee’lùuzh] sticks out his tongue, e.g. for the doctor

rbeluzh lo [rbee’lùuzh loh] sticks out his tongue at (someone)

rcwa lo [rcwààa’ah loh] writes (something) to (someone); throws (something) to (someone) > rcwa

rcwatslo lo [rcwàa’tsloh loh] hides from (someone)

rgue lo [rguèe loh] insults, cusses at, cusses out (someone) > rgue “cusses”

rguiny lo [rguìi’iny loh] borrows (something) from (someone) > rguiny “borrows”

rgwi [rgwi’ih] looks around (in a location — used with a location phrase)

rgwi lo [rgwi’ih loh] looks at, watches, checks out

ria mach lo [rihah ma’ch loh] flirts with, courts (a young woman) (of a young man) > ria

rinda lo [rindàa loh] runs into, encounters (someone) § perf. gunda lo [gundàa loh]

rnab lo [rnààa’b loh] asks for (something) from (someone) > rnab

ru [ru’uh] is (located) inside (usually habitually); exists (in a location) (CB verb) § perf. gu; irr. chu; neut. nu; rzhuën [rzhu’-ëhnn] / ruën “we are located” (all “we” forms may use the normal base or the zhu [zhu’] base)

ru [ru’uh] on the edge of

rzeiby [rzèèi’by] hangs (in a location) § irr. seiby; neut. zeiby

rzi lo [rzìi’ loh] buys (something) from (someone) > rzi

rzu [rzuh] stands (in a location) § irr. su [suu]; neut. zu [zuu]

rzub [rzùu’b] gets placed, is (habitually) placed (on a flat, elevated surface) § irr. sub; neut. zub [zu’ùu’b]

rzub [rzùub] sits, sits down (in a location) § irr. sub; neut. zub

rzubga [rzubga’ah] sits, sits down (in a location) (CB verb) § irr. subga; neut. zubga

rzugwa [rzugwa’ah] stands (in a location) § irr. sugwa; neut. zugwa

tas [ta’s] cup

trasde [tráhsdeh] behind, in back of

zha [zh:àa’] 1. rear end; buttocks; 2. under

zhan [zh:ààa’n] under

Xiëru Zalo Ra Dizh

1. There are several pairs of words on the list of Ra Dizh that are spelled the same. The two ru’s are pronounced the same, but one is a verb and one isn’t, as you’ll learn later in the lesson (these two words are probably related, and connected with the noun ru “mouth”). A more confusing pair of verbs is rzub [rzùub] and rzub [rzùu’b], and the related locational verbs zub [zùub] “is sitting” and zub [zu’ùu’b] “has been placed”. Make sure you can hear the difference in pronunciation betweeen zub [zùub] and zub [zu’ùu’b]. The use of these verbs is described in sections §18.1.1 and §18.1.3. (And consider the comparative note at the end of this lesson, as well.)

2. The words zha [zh:àa’] and zhan [zh:ààa’n] both mean both “under” (as discussed in the lesson) and “buttocks” or “rear end”. In this sense these may be considered to be impolite words by many speakers, as discussed in Lecsyony Tsëda.

3. The perfective of ru, gu, uses the same special spelling rule as rgu “puts down” (Lecsyony Tseiny (15)). You need to add a hyphen before endings beginning with i or ë, as with gu-i “he (dist.) was inside”, gu-ëng “he (prox.) was inside”, and so on.

§18.1. Locational verbs

§18.1.1. Talking about the location of people and animals. Here are some examples of some sentences using locational verbs to talk about where people and animals are located:

|

Zubgoo ricy. |

“You are sitting there.” |

|

Zugwaa re. |

“I am standing here.” |

|

Zu cabai ren. |

“The horse is standing there.” |

|

Nurëng ricy. |

“They are in there.” |

|

Cali natga becw? |

“Where is the dog lying?” |

Locational sentences have three parts: a locational verb, a subject, and a .

| locational verb | subject | location phrase |

| Zubgo | -o | ricy. |

| Zugwa | -a | re. |

| Zu | cabai | ren. |

| Nu | -rëng | ricy. |

A location question like Cali natga becw? begins with cali “where” followed by a locational verb — in this question, cali is like a location phrase. (Cuan “where is” is not used with locational verbs.)

Below is a list of locational verbs. You’ll learn more about these verbs later in the lesson.

|

beb [bèe’b] |

“is located (on a flat, elevated surface)” |

|

natga [nàa’tga’ah] |

“is lying” |

|

nu [nu’uh] |

“is (located); is (located) inside” |

|

zeiby [zèèi’by] |

“is hanging” |

|

zu [zuu] |

“is standing” |

|

zub [zu’ùu’b] |

“is (has been placed) (on a flat, elevated surface)” |

|

zub [zùub] |

“is sitting” |

|

zubga [zubga’ah] |

“is sitting” |

|

zugwa [zugwa’ah] |

“is standing” |

Locational verbs are used to tell the location of something and, very often, to tell its position or orientation. Almost all of them can be translated simply as “is” or “is located” — thus, if someone announced where he was by saying Zugwaa re “I am here”, the fact that he was standing might be apparent to everyone, and you might not consider it to be an important part of the message communicated. (Zua re could be used similarly. Zugwa and zu have very similar meanings, and speakers have trouble explaining any difference between them.) As with habitual and progressive verbs, locational verbs don’t have to refer to the present, but can be used in some cases to refer to other times (though we will generally use present translations for them in this book).

Ricy, re [rèe’] “here”, and re [rèe] “there” are examples of location phrases — these express the location of a subject (or, as you’ll see later, of an action). You’ll learn more about these and other types of location phrases later in this lesson.

Although you would probably expect the “you (sg.)” form of zugwa to be <zugwoo>, the correct form is actually zugoo [zugòo’-òo’]. The w disappears when the final vowel a turns to o (following the regular rule you learned in Lecsyony Tseiny (13)).

Tarea Teiby xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. Are you standing there?

b. Juana is standing here. (Use a different word for “standing” from the one in sentence a.)

c. Where is the teacher sitting?

d. Why are the babies lying there?

e. Where are the pigs (lying)?

f. The doctor is sitting there with my father.

§18.1.2. Talking about the location of inanimate items with zu and natga. You may wonder which locational verb when talking about inanimate (non-living) items like boxes or books. While it is clear whether a man or a dog is lying down or standing, how do you know when a book is lying or standing?

If the inanimate item is tall and thin, like an upright bottle, then you should think of it as “standing” and use the verb zu to give its location. Talking about the bottles on the table in Fot Tyop below, you could say

|

Zu ra botei re. |

“The bottles are there.” |

Just as with people and animals, you don’t always have to express the reference to an item’s position in your English translation. Although the locational verb zu means “are standing” and the sentence could be translated “The bottles are standing there”, it’s fine to think of zu as the equivalent of English “are” in this sentence.

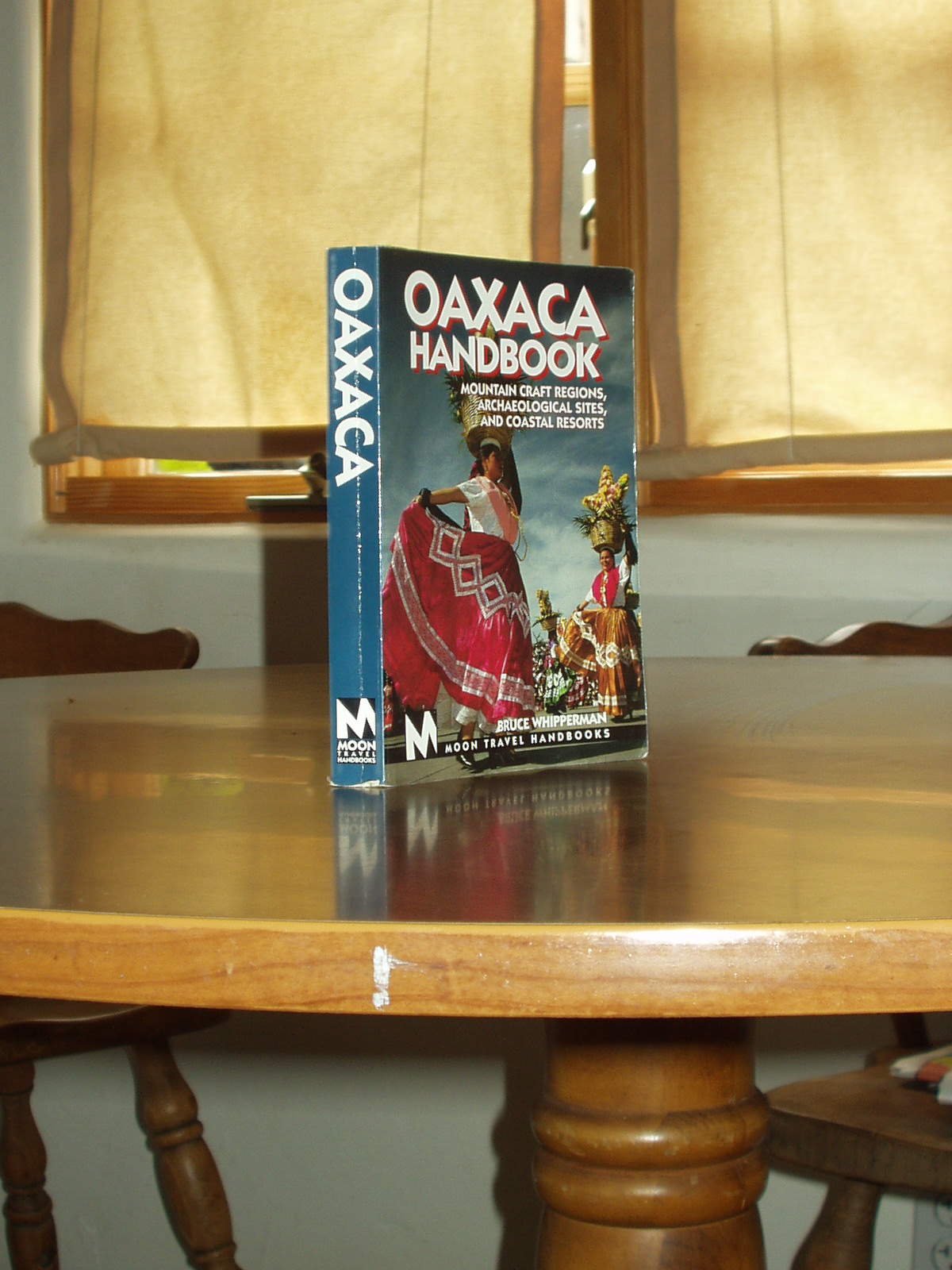

Fot Tyop xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon. A restaurant at the Zocalo in Oaxaca City.**

If the inanimate item is long and thin (like a stick on the ground) or flat (like a blanket), then you should think of it as “lying” and use the verb natga to give its location. You should also think of inanimate items that are compact and round (like a ball) or squarish (like a box) as “lying”, and use natga with them too. For example, we can use natga to talk about the limes in Fot Chon:

|

Natga ra limony ren. |

“The limes are here.” |

Fot Chon xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon. Limes for sale at the market in Tlacolula.

In English we’re not always too specific about specifying position, but this is usually more important in Zapotec. Here are two ways to say “The book is here”:

|

Zu liebr re. |

“The book is (standing) here.” |

|

Natga liebr re. |

“The book is (lying) here.” |

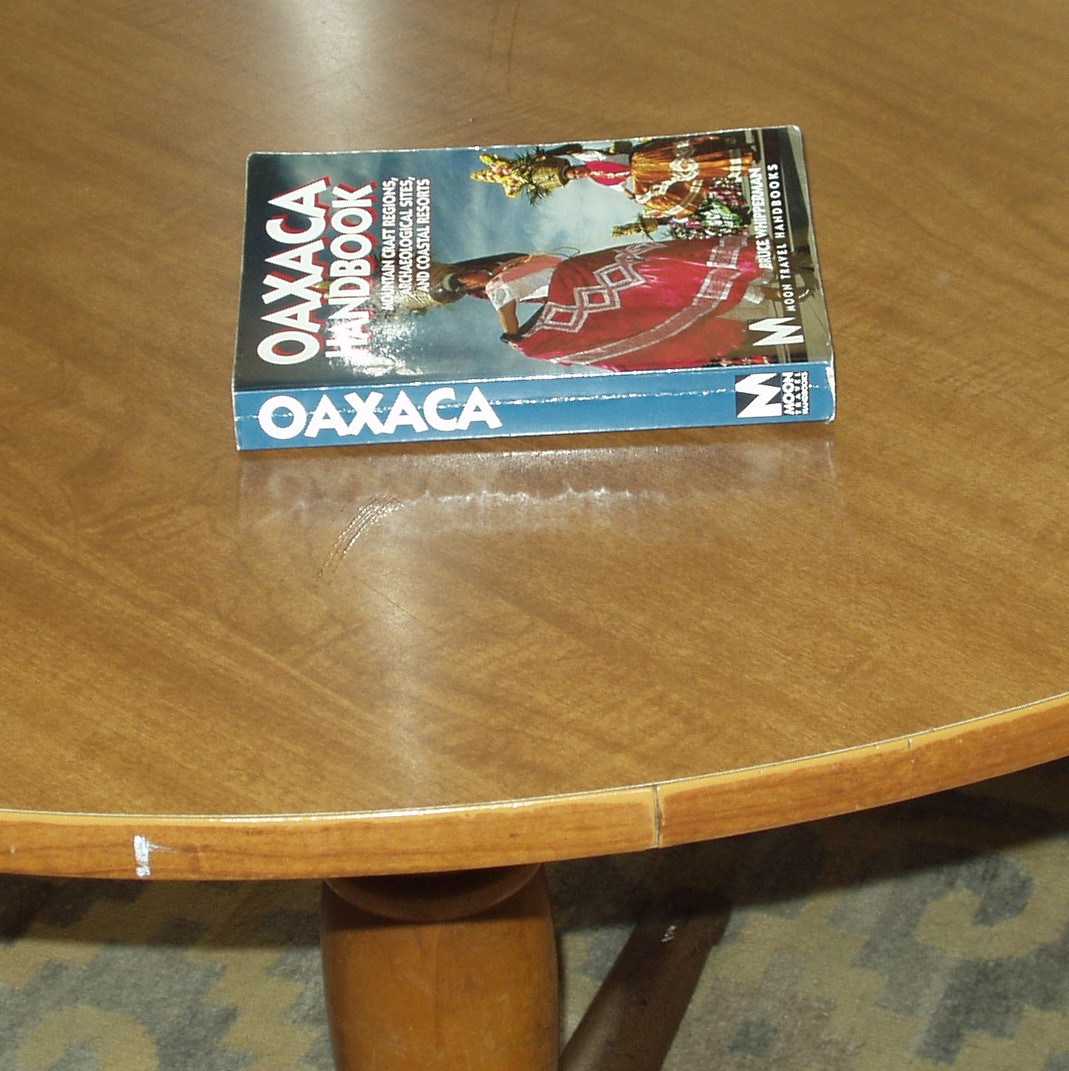

Fot Tap cuan Fot Gai xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon. A book in two positions.

The first sentence could be used to refer to Fot Tap above, where the book is standing upright. The second could be used to refer to Fot Gai in which the book is lying flat.

Listen to Zapotec speakers, and pay attention to what locational verbs they use! When you do this, you’ll learn some surprising things about how to express location. For one thing, the “sitting” verbs zub [zùub] and zubga are only used to talk about the position of people and animals, never to talk about the position of inanimate items (other than, perhaps, dolls or stuffed animals!). (The locational verb zub [zu’ùu’b] “is placed” can be used with inanimate subjects, as described in section §18.1.3.)

There are two ways, then, to ask about the location of something. You can use the special “where is” question word cuan, or you can use cali with a locational verb:

|

Cuan ra botei? |

“Where are the bottles?” |

|

Cali zu ra botei? |

“Where are the bottles?”, “Where are the bottles standing?” |

|

Cuan Lia Glory? |

“Where is Gloria?” |

|

Cali zubga Lia Glory? |

“Where is Gloria?”, “Where is Gloria sitting?” |

There is not a great difference between the two — but if you use cali, you have to make sure the locational verb you choose is appropriate. (See what your teacher thinks!)

Tarea Tyop xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa. Pay special attention to the choice of locational verb by thinking about the shape or orientation of the subject.

a. The pots are there.

b. Where are the bottles? (Use cali.)

c. Where is the glass? (Use cali.)

d. Those blankets are there.

e. Your books are here.

f. The building is there.

g. Ignacio said, “The basket is here.”

§18.1.3. Talking about the location of inanimate things with nu, beb, and zub. %%The Zapotec locational verbs nu, beb, and zub don’t necessarily tell you about the posture or orientation of their subjects. Here are some examples.

|

Nu liebr ren. |

“The book is in there.” |

|

Beb gues re. |

“The pot is there.” |

|

Zub botei ricy. |

“The bottle is (placed) there.” |

The verb nu “is (located) inside” doesn’t say anything about the shape or orientation of an item (unlike the verbs zu and natga); but it does say something about where the item is located: inside something else. If it’s possible to use nu, speakers often prefer to use this verb rather than a locational verb referring to position. Look at Fot Xop below. You may think that it would be appropriate to say <Natga guetxtily ren>, since the bread is round. However, since the bread is located inside the plastic bag, a better way to refer to its location is to say something like

|

Nu guetxtily ren. |

“The bread is in there.” |

Similarly, even though the flowers in Fot Gaz are positioned so that they are long and tall, it is not appropriate to say <Zu ra gyia re>. Since the flowers are located inside something else, it’s better to say something like

|

Nu ra gyia re. |

“The flowers are in here.” |

Ra Fot Xop cuan Gaz xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon. Bread in a bag and flowers in a bag.

The locational verb beb is used to refer to the location of an inanimate item on a raised, flat surface (such as a table, for example). Beb is only used with inanimate subjects that are not permanently in position (for example, it’s not used about houses) and that don’t have obvious ways of moving (like feet or wheels).

(Consider Fot Gai above. Can you think of another way to describe where the book is, now? Speakers may prefer to use beb over a locational verb referring to a specific position if both are possible.)

There are two different verbs written as zub, although these are pronounced differently. The first one is zub [zùub] “is sitting”, which, as we’ve seen, is only used about people and animals. The second, zub [zu’ùu’b] “is (placed on a flat, elevated surface)” can only be used about inanimate items. As you can see, only one of these two verbs (at most) could be appropriate in any given situation. (Make sure you can pronounce the difference between these two verbs!)

The difference between zub “is placed” and beb is that with zub “is placed” you know that the item has been put in its position by somebody. (With this in mind, can you think of a third way to describe Fot Gai?)

§18.1.4. Choosing a locational verb: a summary. Talking about where things are located in Zapotec is very different from in English! The chart below will help you choose the appropriate verb for doing Tarea Chon below.

Tarea Chon xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Practice deciding which locational verbs to use by choosing an appropriate locational verb for each item listed below and making up a Zapotec sentence about it, using ren, re, or ricy for your location phrase. When you are finished, translate your sentences into English.

a. bchily

b. da

c. bar

d. blal

e. becw

f. mna

g. tas

h. botei

| subject to be located | specifications | locational verb |

| If the person or thing is located inside of something else… | use nu. | |

| If the person or thing is hanging… | use zeiby. | |

| If it’s inanimate and located on an elevated surface… | and you want to say that it was placed there by someone… | use zub “is placed”. |

| and you don’t know or don’t want to say that it was placed there … | use beb — or continue below…. | |

| If it’s inanimate, and you don’t want to specify that it’s located on an elevated surface…. | and it’s tall (like a bottle) or positioned so that it is tall (like a book standing up)… | use zu or zugwa. |

| and it’s long and thin (like a stick on the ground), or flat (like a blanket), or compact (like a ball or box), or positioned flat (like a book lying down)… | use natga. | |

| If it’s a person or an animal… | and the person or animal is standing… | use zu or zugwa. |

| and the person or animal is sitting… | use zub “is sitting” or zubga. | |

| and the person or animal is lying down… | use natga. |

There are many other things you’ll learn about the use of locational verbs as you listen to speakers using Zapotec. In particular, listen to how speakers use the verb nu. You’ll probably find that speakers can use this verb in additional cases!

§18.2. Forms of locational verbs

Locational verbs are examples of a special type of Zapotec verb stem called the neutral (they are not the only neutral verbs — you already know the neutral verbs ca “has, is holding” and na “said”, and you’ll learn others in later lessons). Neutral verbs usually express a state of being, such as the fact that something is in a certain position in a location. (Na is an exception here, since it expresses an act of saying.)

Here are the habitual stems that correspond to the new locational verbs:

|

ratga [ràa’tga’ah] lies down (in a location) rbeb [rbèe’b] gets (put) into a position (on a surface); is (habitually) in a position (on a surface) ru [ru’uh] is (located) inside (usually habitually); exists (in a location) rzeiby [rzèèi’by] hangs (in a location) rzub [rzùu’b] gets placed, is (habitually) placed (in a location) rzub [rzùub] sits, sits down (in a location) rzubga [rzubga’ah] sits, sits down (in a location) rzu [rzuh] stands (in a location) rzugwa [rzugwa’ah] stands (in a location) |

Like other habitual stems, these verbs are used to describe events that happen habitually or customarily. They are used much less often than the corresponding neutral stems.

As you can see, the neutral verbs natga and nu are formed by dropping the r of the habitual stems ratga and ru and adding an n prefix — but the other verbs are formed by dropping the r- habitual prefix. (As you can see, many location verb bases start with z.)

Vowel-initial bases and a few others have an n- neutral prefix, but many neutral stems have no prefix. This means that for many verbs the neutral form is the same as the base of the verb, but sometimes there is a change in the vowel pattern (compare the difference between the KC vowel pattern of rzub “gets placed” with the CKC pattern of zub “is placed”, or the B pattern of rzu and the PP pattern of zu, for example). Make sure you can pronounce all of the new verbs in both the neutral and the habitual forms, and that you can identify these when your teacher says them.

The perfective stem of ru is gu [gu’uh], and the perfective stem of ratga is guatga [gùa’tga’ah]. The perfective stem of rbeb is wbeb [wbèe’b], following the regular rule for verbs whose bases start with b. The perfective stems of the new verbs whose bases (and neutral forms) start with z use the regular perfective prefix b.

The irrealis stem of ru is chu [chu’uh], the irrealis stem of ratga is gatga [gàa’tga’ah], and the irrealis stem of rbeb is cweb [cwèe’b].

The irrealis stems of the locational verbs that start with z are formed by changing the z at the beginning of these verbs to s:

|

seiby [sèèi’by] will hang (in a location) sub [sùub] will sit (in a location) sub [sùu’b] will be placed (in a location) subga [subga’ah] will sit (in a location) sugwa [sugwa’ah] will stand (in a location) su [suu] will stand (in a location) |

Most locational verbs do not have progressive stems. Here are two that do:

|

cayatga is lying down (in a location) cazubga is sitting down (in a location) |

Usually, however, progressive ideas are expressed with neutral forms of locational verbs.

You may have noticed that the new verb rbeb is the same as the verb you learned earlier meaning “rides”. In this meaning, rbeb is not a locational verb. The progressive stem for rbeb refers only to the “riding” meaning:

|

Cabebëng gwuan. |

“He’s riding the bull.” |

Tarea Tap xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Change each of the Zapotec sentences below so that it uses a habitual verb. Then translate your new sentence into English.

a. Seiby foc re.

b. Cweb gues re.

c. Blal sub ren.

d. Cali chu muly?

e. Cayatga becw ricy.

f. Mes bzubga re.

g. Ra botei zu ricy.

h. Jwany sundi ren.

§18.3. Prepositions

Look at the pairs of sentences below. The second sentence in each pair contains an added phrase that adds information to the first sentence.

|

Bzuatu e? Bzuatu cuan Bed e? |

“Did you play?” “Did you play with Pedro?” |

|

Bilya teiby liebr. Bilya teiby liebr par xnan Lia Glory. |

“I read a book.” “I read a book for Gloria’s mother.” |

|

Bzubga doctor. Bzubga doctor trasde gyag re. |

“The doctor sat down.” “The doctor sat down behind that tree.” |

These added phrases begin with . You’ve known the preposition cuan for some time, of course, though we have not used that label for this word up to now. Prepositions like cuan, par [pahr] and trasde [tráhsdeh] help us to understand how noun phrases and names like Bed, xnan Lia Glory, and gyag re are related to the event that the sentence is talking about. These noun phrases are neither the subject nor the object of the sentences that include them. Rather, they and the preposition tell us something more about the event — who else was involved, who something was done for, or where something took place, for example. (English has prepositions too, including with, for, behind, and many others, including some longer phrases such as on top of or in back of.)

Noun phrases or names form prepositional phrases with the prepositions that they follow:

|

cuan Bed |

“with Pedro” |

|

par xnan Lia Glory |

“for Gloria’s mother” |

|

trasde gyag re |

“behind that tree” |

A prepositional phrase consists of a preposition plus a following noun phrase, which is called the or the object of the preposition — thus, for example, Bed is a prepositional object in cuan Bed, and we could say that Bed was the object of cuan.

Zapotec has two types of prepositions. Most , including cuan, par, trasde, and a number of others, were borrowed from Spanish. Objects of Spanish prepositions can be expressed with free pronouns:

|

cuan naa |

“with me” |

|

par yuad |

“for you (form pl.)” |

|

trasde lai |

“behind it (dist.)” |

Here’s the pattern that these phrases use:

| Spanish preposition | free pronoun prepositional object |

|

cuan |

naa |

|

par |

yuad |

|

trasde |

`lai |

Tarea Gai xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa. Then practice reading each of your sentences out loud.

a. She washed the shirt for you.

b. They are walking around with her.

c. Are you standing behind them?

d. I warmed the coffee for you (form.).

e. I’ll carry the books for him.

Occasionally you’ll hear speakers use other meanings for these prepositions. Here’s an example from Blal xte Tiu Pamyël in which par expresses “to”:

|

Mnabën teiby abenton par Los Angl. |

“We thumbed a ride to Los Angeles.” |

Listen, and you’ll learn more expressions that use Spanish prepositions. You’ll also discover that there are few prepositions in this group that were not borrowed from Spanish — but we call them “Spanish prepositions” anyway, because they work differently from the second group of prepositions, which are described in the next section.

§18.4. Location phrases with prepositions

Native prepositions. Trasde gyag re is a location phrase in the sentence

|

Bzubga doctor trasde gyag re. |

“The doctor sat down behind that tree.” |

Trasde gyag re uses the Spanish preposition trasde. But most Zapotec location phrases use , not Spanish prepositions. Native prepositions are almost all original Zapotec words, not words borrowed from Spanish. One native preposition that you already know is xten. Most native prepositions are used in expressing location, as in the following examples:

|

Zubga becw dets mes. |

“The dog is (sitting) behind the table.” |

|

Zugwa becw lo mes. |

“The dog is (standing) on the table.” |

|

Natga becw ni mes. |

“The dog is (lying) under the table.” |

|

Zub gues ru mes. |

“The pot is (placed) on the edge of the table.” |

|

Zeiby foc guecy mes. |

“The light bulb is (hanging) above the table.” |

|

Nu muly lany zhimy. |

“The money is in the basket.” |

|

Zu doctor dets mna re. |

“The doctor is standing behind that woman.” |

|

Zu doctor lo mna re. |

“The doctor is standing in front of that woman.” |

These sentences use the native prepositions dets [dehts] “behind”, lo [loh] “on” and “in front of”, ni [ni’ih] “under”, ru [ru’uh] “on the edge of”, guecy [gue’ehcy] “above”, and lany [làa’any] “in”. (There are thus two words for “behind” or “in back of”, trasde and dets. Because dets is the native preposition, many people may consider it more correct. But most speakers use both of these words!)

Most of these words are familiar to you already. These native prepositions can also be used as nouns naming parts of the body: dets “back”, lo “face”, ni “foot”, ru “mouth”, guecy “head”, and lany “stomach”. Valley Zapotec speakers instinctively know whether one of these words is used to name a body part or as a preposition telling how the following prepositional object is related to the rest of the sentence. Probably it will also be very clear to you whether one of these words is used as a preposition or an e-possessed noun in any given sentence.

There are a few other native prepositions that you need to learn. Cwe [cwe’eh] means “beside” or “next to”. (This word is related to a word for “side” (of a body or something else) that some but not all speakers feel is correct; we will not use cwe to mean “side” in this book.) Two other words for “under” are zha [zh:àa’] and zhan [zh:ààa’n], both of which also mean “buttocks” or “rear end” (and, as noted in the Ra Dizh, are considered to be rather impolite words in this sense by many speakers).

The native prepositions often may be translated with several different English prepositions; for example, guecy may often mean “on” or “at the very top of” rather than “above”, ni can mean “at the foot (or base) of”, and lo means both “on” and “in front of”. Speakers also vary in how they use the prepositions: for example, some speakers use lany to mean “under” in certain situations, though in this book we will use only ni, zha, or zhan to mean “under”. Sometimes the preposition a Zapotec speaker chooses may make sense, though it might not be the one you would use in English, as in

|

Bed cuan na byon San Diegw lany autobuas. |

“Pedro and I went to San Diego on the bus.” |

In English, we say “on” here, but in fact, if you think about it, “in” makes more sense! (There is no preposition before San Diegw. You can use a place name destination with a form of ria “goes” without a word meaning “to”. You’ll learn more about using place names without prepositions sentences in Lecsyony Galy.)

Here are some examples with focused location phrases:

|

Dets zhyap zubga Bed. |

“Pedro is (sitting) behind the girl.” |

|

Ru mes zub gues. |

“The pot is (placed) on the edge of the table.” |

|

Lany zhimy nu muly. |

“The money is in the basket.” |

The most common position for location phrases is before the verb, especially when answering a “where?” question. This pattern doesn’t involve as much emphasis as an English sentence like Pedro is sitting behind the girl, so the prepositional phrase is not underlined in the translations. Notice that when you focus a location phrase you must include the preposition, and put the whole location phrase (for example, dets zhyap or lany muly) at the beginning of the sentence. (In English we can say things like The basket is what the money is in, with the preposition at the end of the sentence. This is not possible in Valley Zapotec. There is always a prepositional object next to a Valley Zapotec preposition, and a Valley Zapotec sentence can’t end with a preposition without something following it.)

Now, here’s another type of location sentence you may hear:

|

A becw zubga dets mes. |

“The dog is (sitting) behind the table.”, “There’s a dog (sitting) behind the table.” |

Putting a before a focused subject of a locational sentence can express two meanings. Often this type of sentence corresponds to ordinary focus, and might be used to answer a “where?” question. Sometimes, though, these a sentences are more like English “there” sentences. Listen to how Zapotec speakers use a in location sentences, and you’ll learn more about this.

Tarea Xop xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Now that you’ve learned about prepositions, look again at the following pictures from this lesson and, for each one, answer the question given in Zapotec. Your answer should use a locational verb and a location phrase containing the noun given in parentheses. Finally, translate your sentence into English, as in the example.

Example. Fot Tyop: Cuan ra botei? (mes). A ra botei lo mes / Ra botei zu lo mes. “The bottles are on the table.”

a. Fot Chon: Cuan ra limony? (gyets)

b. Fot Tap: Cuan liebr? (mes)

c. Fot Gai: Cuan liebr? (mes)

d. Fot Xop: Cuan guetxtily? (bols)

e. Fot Gaz: Cuan ra gyia? (bols)

f. Fot Teiby: Cuan nguiu? (mna)

Objects of native prepositions. The major difference between native and Spanish prepositions concerns how you express prepositional objects that are pronouns. With Spanish prepositions, as you’ve learned, a prepositional object can be a free pronoun. With native prepositions, however, you have to use a bound pronoun to express a prepositional object:

|

Detsa zubga Jwany. |

“Juan is (sitting) behind me.” |

|

Zugwa Lia Len loo. |

“Elena is (standing) in front of you.” |

|

Cweën natgaëng. |

“He is lying next to us.” |

|

Detsi zu ra botei. |

“The bottles are (standing) behind it.” |

|

Natga ra guet lanyëng. |

“The tortillas are (lying) in it.” |

|

Zu Nach cwia. |

“Ignacio is standing next to me.” |

Here’s the pattern:

| native preposition | bound pronoun prepositional object |

|

dets |

-a |

|

lo |

-o |

|

cwe |

-ën |

|

lany |

-ëng |

|

cwi |

-a |

These examples show that the bound Zapotec pronouns may have an additional English translation. We’ve seen them used as subjects (for example, -a means “I” and –ën means “we”) and as possessors (for example, –a means “my” and –ën means “our”). As prepositional objects, –a means “me” and –ën means “us”, and so on.

Adding bound pronouns to prepositions to indicate prepositional objects works just like adding bound pronouns to nouns to indicate possessors. You need to use the combination forms of the prepositions when you add bound pronouns, and the same types of changes that can occur with vowel final nouns also happen with vowel final prepositions. This means, for instance, that lo plus the bound pronoun –a is pronounced lua, and cwe plus the bound pronoun –a is pronounced cwia. (For a review of these changes, see Lecsyony Tseiny (13) and Tsëda.)

Locational phrases in sentences. Some verbs, like the locational verbs you learned earlier in this lesson, don’t make sense without a location phrase. Another example of a verb that needs a location phrase is rgwi “looks around”. You have to tell the location in which someone looks around — it doesn’t make sense to use this verb all by itself:

|

Ricy bgwiën. |

“We looked around there.” |

|

Chigwiad lany Ydo Santo Domyengw. |

“You can go and look around in the Santo Domingo Church.” |

(Note that rgwi doesn’t mean “looks around for” — that’s rguily, as you know.) Other verbs can be used either with or without added location phrases:

|

Cayualrëng. |

“They are singing.” |

|

Cayualrëng lany ydo. |

“They are singing in the church.” |

Tarea Gaz xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Part Teiby. Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. Modesta is sitting behind Catalina.

b. Modesta is sitting behind Catalina. (use a different word for “behind”!)

c. They are playing in back of the school.

d. We are standing in the store.

e. Who made the dress for Elena’s mother?

f. The boys looked around in front of the church.

g. The picture is hanging in the church.

h. Chico wrote the letter with that pen.

i. Who is sitting next to the teacher?

j. Why is Pedro standing next to those women?

k. I will look under the table.

l. Three trees are on the very top of the mountain.

Part Tyop. For each of your sentences in Part Teiby, change the prepositional object into a pronoun. Be careful to use the correct type of pronoun!

Part Chon. Now, translate the following sentences once more, assuming that they end as follows rather than as above.

a. … behind me.

b. … behind you.

e. … for you (form.)?

i. … beside us?

j. … in front of you guys?

§18.5. More about lo

Lo “on; in front of” is the most frequently used native preposition, and there are few extra things you need to learn about how it works with other types of objects and meanings.

§18.5.1. Talking about seeing with lo. Most Valley Zapotec expressions that refer to seeing or looking at something express the noun phrase telling who or what was seen as the object of the preposition lo rather than as a regular object. Here are two of these verbs:

|

ran lo [ràann loh] sees rgwi lo [rgwi’ih loh] looks at, watches, checks out |

The verb ran is quite irregular: its perfective is mna, and its irrealis is gan.

These new verb phrases can be used in sentences like the following:

|

Rana lo Bed. |

“I see Pedro.” |

|

Mna Lia Len lua. |

“Elena saw me.” |

|

Cagwiu lo telebisyony e? |

“Are you watching television?” |

|

Chigwi Jwany lo ra budy. |

“Juan is going to go and look at the chickens.” |

Here is the pattern used in these sentences:

| “see” verb | subject | lo | prepositional object | rest of sentence |

|

Ran |

-a |

lo |

Bed. |

|

|

Mna |

Lia Len |

lu |

-a. |

|

|

Cagwi |

-u |

lo |

telebisyony |

e? |

|

Chigwi |

Jwany |

lo |

ra budy. |

In these expressions, lo does not mean “on” or “in front of” (though you usually are facing whatever you are looking at!). It is best just to think of it as part of the “seeing” verb. What would be the object in the English sentence is expressed in Zapotec in a prepositional phrase, as the object of the preposition lo.

The pattern above is the basic pattern, starting with a verb. Of course, you can focus the subject or the prepositional object. Lo plus the following prepositional object form a prepositional phrase, so if you want to focus the item that is seen, you need to focus the whole lo phrase:

|

Lia Len mna lua. |

“Elena saw me.” |

|

Lo ra budy chigwi Jwany. |

“Juan is going to go and look at the chickens.” |

|

Lo telebisyony cagwiu e? |

“Are you watching television?” |

§18.5.2. More ways to use lo. Some complex verbs use lo:

|

rbecy lo [rbèe’cy loh] fights (a bull) rbeluzh lo [rbèe’lùuzh loh] sticks out his tongue at (someone) rcwatslo lo [rcwàa’tsloh loh] hides from (someone) rgue lo [rguèe loh] insults, cusses at, cusses out (someone) rinda lo [rindàa loh] runs into, encounters (someone) |

Here are some sentences that use these new verbs:

|

Jwany cwecy lo guan. |

“Juan will fight the bull.” |

|

Queity cweluzh lua! |

“Don’t stick out your tongue at me!” |

|

Cacwatslong loo. |

“He’s hiding from you.” |

|

Lo Raúl Alba bde Chiecw. |

“Chico cussed out Raul Alba.” |

These vocabulary entries work similarly to those you’ve seen for the “see” verbs in §18.4.1 or for verb phrases that include runy (Lecsyony Tsëbtyop). The first word in the entry is the verb (you’ve seen many of these verbs before, used on their own). Select the right stem of the verb according to the meaning of the sentence you’re expressing. (Irregular stems of verbs are listed in the Ra Dizh and the Rata Ra Dizh, and in the Valley Zapotec Verb Charts.) The subject (whether it is a noun phrase or a bound pronoun) follows the verb. The noun phrase corresponding to the object of the English sentence (taking the place of the item in parentheses in the entries above) follows lo.

As with the “see” expressions in §18.5.1, lo plus the following noun phrase forms a prepositional phrase. So if you want to focus that object, you need to focus the whole prepositional phrase, including lo, as in the last example.

Can you make up a sentence that uses rinda lo?

§18.5.3. More idioms with lo. The following expressions are a bit more complicated than those in the previous section:

|

rbe permisy lo [rbee’eh permi’sy loh] asks permission from (someone) ria mach lo [rihah ma’ch loh] flirts with (a young woman) (of a young man) rcwa lo [rcwààaah loh] writes (something) to (someone); throws (something) to (someone) rguiny lo [rguìi’iny loh] borrows (something) from (someone) rnab lo [rnààa’b loh] asks for (something) from (someone) rzi lo [rzììi’ih loh] buys (something) from (someone) |

These complex verb phrases are used with an extra object noun between the subject and the lo prepositional phrase. As with the expressions in §18.5.2, you already know most of the basic verbs involved.

In the first two, that object word (permisy or mach) is part of the expression — it goes after the subject, before lo.

|

Blia permisy lo xtada. |

“I asked permission from my father.” |

|

Gwe Rony mach lo zhyap. |

“Jeronimo flirted with the girl.” |

(Ria mach lo is used with a subject who’s a young man and an object who’s a young woman.)

With the other new verb phrases, you can add whatever extra object makes sense in the sentence:

|

Lia Len bcwa email lo Lia Glory. |

“Elena wrote an email to Gloria.” |

|

Quinyën muly lo xtad Jwany. |

“We are going to borrow money from Juan’s father.” |

|

Lo Raúl Alba si Rnest blal. |

“Ernesto is going to buy the blal from Raul Alba.“ |

Try making up a new sentence illustrating the use of rnab lo!

Once again, lo plus the following object forms a prepositional phrase. So if you want to focus that item, you need to focus the whole prepositional phrase, including lo, as in the last example above.

Tarea Xon xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Read each of the sentences below aloud. Chiru, bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Ingles.

a. Mnaën lo xnanën.

b. Tu su lo Bed?

c. Gundayu lorëng e?

d. Cagwi Rnest cuan Rony lo blal xte Tiu Pamyël.

e. Natgaa lo da.

f. Ysaguelyu ygwiyu lo xliebra.

g. Cwecyi lo teiby guan.

h. Mna lorëm!**

i. Mna doctor lo buny ni blan muly xte xtadu.

j. Bzub liebr re lo mes!

k. Mnaad lo ydo e?

l. Rata zhi rana loo.

m. Xi ni cacwatslo buny lo polisia?

n. Bcwa mes cart lua.

All of these expressions with lo are idioms, special combinations of words whose meaning is not exactly what you’d expect from their component parts. Many of them use verbs you are already familiar with, such as rbe “takes”, rbecy “puts on (pants)”, rgue “cusses”, rguiny “borrows”, ria “goes”, and rnab “asks for”. In the other cases, the verbs involved are new ones. (When the expression uses one of these familiar verbs, the verb works the same — uses the same stems and combines with pronouns in the same way — in the idiom as it does when used on its own. All the other verbs appear in the Valley Zapotec Verb Charts.)

In each of the new expressions in this section, the meaning of lo is not “on” or “in front of”. With several expressions (rcwa permisy lo, rcwatslo lo, rguiny lo, and rnab lo), lo means “from”. In the case of rcwa lo, lo means “to”. With ria mach lo, the best English translation of lo might be “with”. In some cases, lo does not seem to be easily translated with an English preposition. It’s best to learn these expressions as phrases and to practice using them until they become natural to say and hear.

Tarea Ga xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. Jeronimo asked permission from his (own) mother.

b. I bought three blankets from that woman.

c. Why are you trying to date that girl?

d. When did he fight the bull?

e. Write a letter to Petra!

f. Every day my brother sticks his tongue out at me.

g. When did Santiago borrow that book from her?

h. We will hide from them.

i. Who asked Elena for coffee?

j. Who ran into the doctor in front of this building?

§18.6. Question word questions with prepositions

Here are some questions using prepositions:

|

Xi cuan bcwa Jwany cart na? |

“What did Juan write the letter with?” |

|

Tu dets zubga Lia Len? |

“Who is Elena sitting behind?” |

|

Tu cwe zugwoo na? |

“Who are you standing next to?” |

|

Tu lo bcwatslo Chiecw? |

“Who did Chico hide from?” |

These questions begin with the question words xi and tu, just like the question word questions you learned to form in Lecsyony Tseinyabtyop, and like the corresponding English questions. But note that whereas the English questions end with prepositions, in Zapotec the prepositions come right after the question words, in the following pattern:

| question word | preposition | verb | subject | rest of sentence |

|

Xi |

cuan |

bcwa |

Jwany |

cart na? |

|

Tu |

dets |

zubga |

Lia Len? |

|

|

Tu |

cwe |

zugwo |

-o |

na? |

|

Tu |

lo |

bcwatslo |

Chiecw? |

In English, we normally use prepositions at the end of questions like those above. Another way to form these English questions is to put the preposition at the beginning of the sentence, followed by the question word (as in With what did Juan write the letter?), but this probably sounds quite stilted to you. In Zapotec, however, the question word always comes first.

For now, don’t try to question a “what” object of a native preposition. Instead of something like “What is Juan standing next to?”, then, just ask “Where is Juan?”! You’ll learn more about questions about prepositional objects in Lecsyony Galy.

Tarea Tsë xte Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. Who are Elena and Ignacio standing in front of?

b. Who are you writing that letter to?

c. What did he eat the soup with?

d. Who did Pedro see in the church?

e. Who is my dog lying next to?

f. Who are they looking at?

g. Who did you borrow those pots from?

h. Who did she buy that present for?

i. Who did you buy that blanket from?

j Who did Tomas hide from?

k Who did the doctor insult?

l. Who are you (form.) going to see?

Prefixes

n- [n] (neutral verb prefix, used on neutral verbs with vowel-initial bases)

Comparative note. While speakers of all varieties of Valley Zapotec languages use positional verbs and prepositions to specify locations, the specific verbs they use may vary somewhat, and how those verbs and prepositions are used with different items they are locating may also vary.

For example, speakers vary considerably in terms of how they use the locaational verb beb. In this book, we use beb to refer to the location of any inanimate item (not permanently in position, without feet or wheels) located on a raised, flat surface, but other speakers use it more restrictedly. Some use beb only to talk about the location of items that are long and thin (like a stick), flat (like a piece of paper or a blanket), or compact (like a ball or box) — things that these speakers would think of as “lying”.

Listen as you hear speakers talk about locations, and you’ll learn more about other ways to use locational verbs.

A PHRASE which expresses the location of a SUBJECT or an action within a SENTENCE.

A word used to tell the relationship of a NOUN PHRASE that is neither a SUBJECT nor an OBJECT to the rest of the SENTENCE; abbreviated as "prep.". There are two types of Zapotec prepositions: NATIVE PREPOSITIONS and SPANISH PREPOSITIONS.

The NOUN PHRASE, name, or PRONOUN that follows a PREPOSITION, which together with the preposition forms a PREPOSITIONAL PHRASE. The prepositional object is also called the OBJECT of the preposition.

A Zapotec PREPOSITION that works differently from a NATIVE PREPOSITION. Most Spanish prepositions were BORROWED from Spanish.

A PREPOSITION that works differently from a SPANISH PREPOSITION. Most native prepositions are native Zapotec words, not words that were BORROWED from Spanish.