2. Lecsyony Tyop: Writing Valley Zapotec

This lesson presents written Valley Zapotec. It begins with a history of Zapotec writing (section §2.1), discusses how to learn a new writing system (section §2.2.), and introduces Valley Zapotec vowels and consonants (sections §2.3–2.4). Section §2.5 describes the vowel ë, and section §2.6 diphthongs. Section §2.7 adds a few more important ideas about writing and pronunciation, section §2.8 presents Zapotec alphabetical order, and section §2.9 is a reference chart.

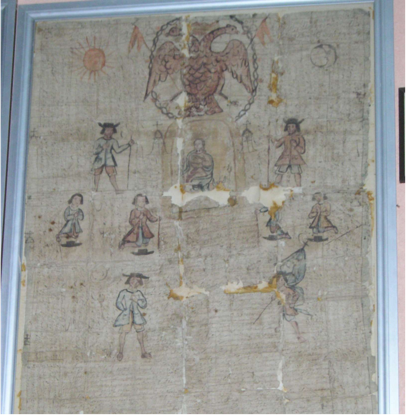

Lecsyony Tyop, Picture 1. A título (land title) from the Colonial period displayed in the municipio (city hall) of San Lucas Quiaviní. (Photograph by Felicia Lee.)

§2.1 A brief history of Zapotec writing

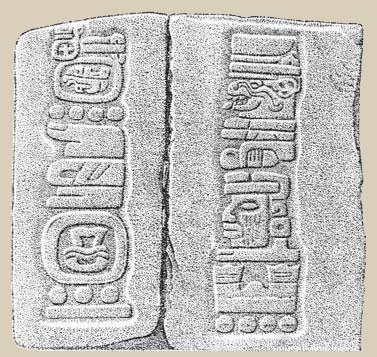

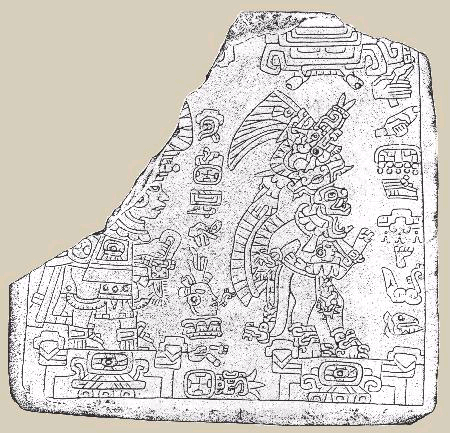

There is no traditional alphabetic writing system for any Zapotec language. Long before the Spanish colonization of Mexico in the 16th century, Zapotec people made some use of pictographic representations (Picture 2), which no one understands today. Early examples of documents written by Zapotecs include pictorial títulos (land titles) like that in Picture 1. Writing systems have been developed for many Zapotec languages both during the Colonial period and in recent years, but most speakers of Zapotec languages don’t write in their language. In this lesson, we’ll introduce the writing system for Valley Zapotec used in this book.

Lecsyony Tyop, Picture 2. Monte Albán, Stelae 12 and 13; Lápida de Bazán (approximately 500 B.C. – 250 A.D.) (www.ancientscripts.com).

Valley Zapotec is actually the variety of Zapotec with the longest (alphabetically) written history: the Spanish missionary priest Fray Juan de Córdova prepared a grammar (Arte) and dictionary of Valley Zapotec which were first published in 1578. The writing system we use here derives directly from Córdova’s system.

However, there have been changes in the Valley Zapotec language since the sixteenth century, so most words in Valley Zapotec look very different now. The table below presents some comparisons between Zapotec words recorded by Córdova and modern Valley Zapotec words. The words are given in three columns (with their translations into English). The first column gives the spelling used in Córdova’s dictionary for the word as used in sixteenth century Colonial Valley Zapotec. (Córdova often spelled the same word in more than one way in different places in the dictionary; these are just examples.) The second gives the modern Valley Zapotec form in the writing system we will use in this course. The third is a , showing how the written Valley Zapotec forms are pronounced. Your teacher will pronounce each modern word for you, and you can hear these words in the audio materials that accompany this book. (Pronunciation guides are explained beginning in the third lesson in this book, Lecsyony Chon.)

| Córdova (16th century) | Modern Valley Zapotec | pronunciation | English meaning |

| càa | ga | [gààa’] | “nine” |

| chij | tsë | [tsêë’] | “ten” |

| chij | zhi | [zh:ih] | “day” |

| máni | many | [ma’any] | “animal” |

| ñaa | na | [nnaàa’] | “hand” |

| nagàce | ngas | [nga’as] | “black” |

| naxiñàa | xnia | [xniaa] | “red” |

| pèco | becw | [bèe’cw] | “dog” |

| péo | beu | [be’èu] | “month” |

| pij | bi | [bihih] | “air” |

| pizàa | bzya | [bzyààa’] | “bean” |

| quie | gyia | [gyììa’] | “flower” |

| tícha | dizh | [dìi’zh] | “word” |

| xàna | zhan | [zh:ààa’n] | “under” |

| yòho | yu | [yu’uh] | “house” |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 1. (With Ana López Curiel.)

As you look at the examples, you’ll see that a major difference between the older Zapotec words and the modern ones is that many modern words have dropped vowel letters (a, e, i, o, u) that were present in the Colonial words (for example, compare Córdova’s ticha “word” with modern dizh, or nagàce “black” with ngas, which has dropped both its first and third vowels). There are other differences involving vowels too. For example, Córdova often wrote vowels double (for example, ñaa “hand”) or with marks (marks written over a vowel letter, as in pèco “dog” and máni “animal”). In our modern writing system, we do not write any vowels doubled or with accents (other than the two dots over the ë letter, used in words like tsë “ten”). No one knows exactly what the doubled and accented vowels meant for Córdova, since we do not have any audio recordings of sixteenth century Zapotec. However, most likely Córdova was trying to use these spellings to record the different types of vowels like those you will see indicated in the pronunciation guide.

There are also differences in the way Córdova writes consonant letters. For some reason, Córdova very seldom wrote the letters b, d, and g. Thus, you can see that c in càa “nine” corresponds to a modern g sound, while c in pèco “dog” corresponds to a modern c sound. Scholars who have studied Córdova’s spellings don’t fully understand what this means. Maybe sixteenth century Valley Zapotec had fewer b‘s, d‘s, and g‘s than the modern language, or maybe Córdova just didn’t hear things clearly. Whatever the answer, it’s clear that Valley Zapotec pronunciation has changed a lot in 400 years.

Since the time of Córdova, people have used a number of different ways of writing Valley Zapotec. The New Testament has been translated into the San Juan Guelavía variety of Valley Zapotec using one system. Another, more complicated way of writing Zapotec (similar to the pronunciation guides in this book) is used in the San Lucas Quiaviní Zapotec dictionary. Individual speakers have often written words down just as they heard them, as in the signs in Picture 3 below and Picture 2 of Lecsyony Chon. The system presented in this book is a new, simplified system.

Lecsyony Tyop, Picture 3. A cali chiu bicycle taxi in Tlacolula. The sign on the back says “Ecological Transport: Cali Cheu (Where Are You Going?)”. This sign was written in a different writing system than the one used in this book.

Photograph by Ted Jones.

§2.2 Learning a new writing system

Like all languages, Valley Zapotec has both vowel and consonant sounds. sounds are made with your mouth open, with a continuous stream of air coming out without any obstruction. sounds are made with the stream of air coming from the lungs interrupted at some point by contact or constriction between the tongue and some other part of the mouth, between the two lips, or between other speech organs. Most of the Valley Zapotec sounds are written with letters that are used just about the same as in English (or Spanish). Some sounds in Zapotec, though, are not found in either English or Spanish, and some letters are used in ways that you may find unexpected.

When learning to read and write a new language, it’s important to remember that the pronunciation rules that work for one language do not necessarily apply to another language. Most people in California know of English speakers who pronounce pollo (as in El Pollo Loco) to rhyme with the word solo, or of Spanish speakers who pronounce the English words beat and bit the same. These “mistakes” occur because the speakers assume that the spelling and pronunciation rules of one language work for the other language, which is not necessarily true. In learning to read Valley Zapotec, you will need to set aside some of the things you’ve learned about reading English, Spanish, or any other language you may know, because Valley Zapotec is a different language with its own sounds and pronunciation rules.

The major difference between the Valley Zapotec writing system and the spelling systems of English and Spanish is that our Valley Zapotec writing system is completely regular.

As you probably already know, English spelling is very irregular. English sounds — especially vowel sounds — are often written in more than one way (way, weigh, raid, and rate, for example, all contain the same vowel sound), and the same English spelling often represents more than one sound (for example, the ough in cough, through, rough, and though represents four different vowel sounds). English spelling needs to be memorized — it’s not always possible to know how to pronounce an unfamiliar word from its spelling, or to know how to spell an unfamiliar word from its pronunciation.

Spanish spelling is more regular than English, because a Spanish speaker can almost always tell how to pronounce a word from its spelling. However, Spanish speakers often have trouble spelling unfamiliar words because there are many letters and letter combinations that represent the same sound, and there is one letter, x, that can be pronounced in several ways. Thus, speakers of Mexican or North American Spanish pronounce ll and y alike, so they may be uncertain about how to spell some words pronounced with a y sound. There are similar possibilities for confusion between s, z, and c and between g and j, and speakers are often puzzled about where to use the letter h.

Once you learn the Valley Zapotec spelling rules, however, you’ll be able to write any new word you hear.

Learning to use the pronunciation guides is more tricky, but they are very regular too. Once you understand them, you will be able to pronounce any new word following its pronunciation guide. (For more about pronunciation guides, see Lecsyony Chon and Lecsyony Tap.)

In introducing the Zapotec sounds below, we will make comparisons with English and Spanish sounds, since Zapotec has some things in common with both languages. However, no two languages have exactly the same pronunciations even for sounds that are spelled alike: no Zapotec sound is exactly like any English or Spanish sound (just as no English or Spanish sound is exactly like any Zapotec sound). The comparisons are given only to help you understand what sounds are being discussed.

As each Zapotec sound is presented during this lesson, listen carefully to your teacher’s pronunciation and try to imitate the new sounds exactly the way your teacher pronounces them. Every speaker of a language pronounces words somewhat differently from every other speaker of that language. None of the different pronunciations different Zapotec speakers use is more “correct” than another. In this lesson, we will mention some ways that speakers differ in their pronunciation, but we will not discuss all of these. Your teacher may sometimes use a different pronunciation from the one given in a lesson. This does not mean that your teacher’s pronunciation is wrong, only that his or her usage is slightly different from that of the speakers who helped with these lessons.

§2.3. Valley Zapotec vowel sounds

Five of the basic Valley Zapotec vowel sounds are pronounced just about the same as the five vowel sounds of Spanish: a as in Spanish amor “love” (or roughly as in English father), e as in Spanish eso “that” (or roughly as in English bet), i as in Spanish iguana “iguana” (or roughly as in English police), o as in Spanish hola “hello” (or roughly as in English rodeo), and u as in Spanish uva “grape” (or roughly as in English hula). (There is also a sixth Valley Zapotec vowel sound, which is introduced in section §2.5.)

Here are Zapotec examples containing each of these vowel sounds. We write Zapotec words and sounds here in boldface with their translations in quotation marks. The pronunciation guide for each word is given in square brackets [ ], just like the pronunciation section of most standard dictionaries. Below the table is a video in which you can hear each of these words pronounced. (These examples use letters representing consonants that have about the same pronunciation as consonants of English and Spanish. For more about these consonant letters and sounds, see section §2.4.)

| vowel | Zapotec spelling | English translation | pronunciation |

| a | syuda | “city” | [syudaa] |

| e | cafe | “coffee” | [cafee] |

| i | wi | “guava” | [wii] |

| o | mon | “doll” | [moon] |

| u | zu | “is standing” | [zuu] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 2. Five of the basic vowel sounds. (With Ana López Curiel.)

The five examples above show several additional things about Zapotec. First, several of the examples are words that were borrowed into Zapotec from Spanish. There are many Spanish loanwords in Zapotec. The Zapotec words syuda, cafe, and mon are quite similar to the Spanish words ciudad, café, and mona, which speakers have borrowed. But many other loanwords were borrowed from Spanish so long ago that they have changed considerably in both pronunciation and meaning, and sometimes are not recognizable as borrowings. If you know Spanish, you may have fun trying to identify Spanish borrowings in Zapotec, but for the most part, we will not point these out specially. (Most Zapotec words, of course, are not borrowed. The examples above were chosen simply because of the sounds they contain.)

A is a rhythmic unit in a word. The English words a, is, in, and word have one syllable each, while English and rhythmic have two syllables, and syllable has three. (Try seeing if you can identify the number of syllables in a few more English words. As a word like more shows, the number of syllables is not necessarily the same as the number of vowels in the word.) The Zapotec words syuda and cafe each have two syllables, while wi, mon, and zu each have one syllable. There are two types of syllables in Zapotec words, syllables (whose spelling contains just one vowel, like all those in these words) and diphthong syllables (whose spelling contains more than one vowel — you’ll learn more about these in section §2.6).

Zapotec vowel pronunciation is complicated. Just as in English, there are sets of words that are written the same but pronounced differently. You will learn the correct pronunciation for many words simply by imitating your teacher, but the pronunciation guide will always be available to help you pronounce unfamiliar words.

If you look at the pronunciation guide column above, you’ll see that each word there is written with a double vowel in the last syllable (in all the words but mon, the double vowel is — it occurs at the end of the word). The pronunciation guide for a Zapotec syllable may contain from one to three vowels. Here’s an example: think about the length of time it takes to say the vowels of each syllable in the word cafe. The second vowel sounds longer, right? Now, look at the pronunciation guide for this word. The vowel in the second syllable is written with two e‘s, while the vowel in the first syllable is written with only one a. That’s because the second syllable is longer. You can check this out in the video below.

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 3. Different syllable lengths in cafe. (With Ana López Curiel.)

There are many different ways of pronouncing vowels in Zapotec, and we’ll explain these and their pronunciation guides more fully in Lecsyony Chon. To keep things simple, though, all the words used to introduce consonant sounds in the next section will have this same type of vowel pronunciation you’ve already seen in this lesson.

Another thing to learn about vowel pronunciation in Valley Zapotec is that some speakers pronounce certain words with different vowels. You should always try to pronounce words the way your teacher says them and to write them following your teacher’s pronunciation, even if that is different from the way the words are written in this book.

§2.4. Valley Zapotec consonant sounds

§2.4.1. Sounds that are like both English and Spanish. Many Zapotec consonant sounds are pronounced quite similarly to the corresponding sounds of both English and Spanish. Some of these sounds are ch, f, l, m, n, p, s, and t. Ch is a (a sequence of two letters) that represents a single sound. There are many such combinations in Zapotec, just as in both English and Spanish.

Below are some examples of words containing such similar sounds. You can hear them in the video that follows the list. (Feliciano and Cayetano are men’s names. Information on Zapotec names and how to use them is included in section S-2.)

| consonant | Zapotec spelling | English translation | pronunciation |

| ch | Chan | “Feliciano” | [Chaan] |

| f | cafe | “coffee” | [cafee] |

| l | lechu | “lettuce” | [lechuu] |

| m | mon | “doll” | [moon] |

| n | canel | “cinnamon” | [caneel] |

| p | plati | “cymbals” | [platii] |

| s | solisitu | “application” | [solisituu] |

| t | Tan | “Cayetano” | [Taan] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 4. (With Ana López Curiel.)

Another Zapotec sound that is pronounced like a Spanish and English sound is c. Zapotec c always has about the same sound as Spanish c in casa “house”, or any Spanish word where c comes before the vowels a, o, and u, which is about the same sound as English k (and many English c‘s, as in car). Here’s a Zapotec example, which you can listen to in the video that follows:

| c | capi | “shrine” | [capii] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 5. (With Ana López Curiel.)

Zapotec c is never pronounced like Spanish c in cine “movies” or like English c in cinema.

§2.4.2. Sounds that are more like Spanish. Most other Zapotec consonant sounds are pronounced about the same as some sound in Spanish or some sound in English. The Zapotec sounds b, d, and g, for example, are more like the b, d, and g sounds of Spanish than the corresponding English sounds. Here are some examples, which you can hear in the video that follows. Since it’s easiest to learn these pronunciations by imitation, try pronouncing them yourself.

| b | Bed | “Pedro” | [Beed] |

| d | dad | “dice” | [daad] |

| g | gan | “gain” | [gaan] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 6. (With Ana López Curiel.)

One Zapotec letter is pronounced almost exactly as in Spanish, but very differently from the way it is usually pronounced in English. This is j, as in Spanish jugo “juice”. Remember: Zapotec j is not pronounced like English j in joke. Here is an example, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| j | jug | “juice” | [juug] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 7. (With Ana López Curiel.)

Like Spanish, Zapotec has two r sounds, r and rr. These are pronounced just about the same in Zapotec and Spanish, as in Spanish pero “but” and perro “dog”. Neither Zapotec r or rr is pronounced like English r or rr in roar or mirror. The Zapotec r is pronounced very much like English t in a word like city! There is no English equivalent of Zapotec rr, which is a “rolled” or “trilled” r (listen to your teacher!). Here are some examples that will let you compare the r and rr sounds. Once again, you can listen to them in the video below:

| r | ri | “are around” | [rii] |

| r | ra | “all” | [raa] |

| rr | rran | “frog” | [rraan] |

| rr | rrelo | “watch” | [rreloo] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 8. (With Ana López Curiel.)

(It’s important to remember that the single Zapotec r in words like ri or ra always has a sound like that of Spanish r in pero. Even though Spanish words beginning with r, like rana (the source for Zapotec rran) are written with only a single r, they are pronounced with the rr sound by Spanish speakers. Zapotec words beginning with r rather than rr, like ri and ra, do not start with the rr sound of Spanish rana.)

You might think that rr is a letter combination representing a single sound, exactly like ch or zh, but that’s not completely true. Rr comes from a single Spanish sound in words borrowed from Spanish, like the examples above. When rr occurs in a Zapotec word that’s not borrowed from Spanish, however, it is actually a sequence of two sounds, one r followed by a second r (you’ll see some examples in Lecsyony Tap). Because it seems to represent a single sound in many words, we alphabetize it separately from the rr, but it’s often best to think of it as a very special case of two sounds.

(See section §2.4.4 for more about the pronunciation of Zapotec r before another consonant.)

2.4.3. Sounds that are more like English. The Zapotec sound z is pronounced about like an English z sound (as in zoo), but not like a Spanish z (as in zona “zone”). Here is an example, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| z | zu | “is standing” | [zuu] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 9. (With Ana López Curiel.)

The Zapotec letter combination zh represents a sound that is used in English, but not written in a consistent way. It is about the same as the sound of the s in English pleasure. Here is an example, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| zh | zhar | “vase” | [zhaar] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 10. (With Ana López Curiel.)

(Almost the same sound is used by some Latin American Spanish speakers when pronouncing the letters y and ll, as in yo “I” or llave “key”. Other Spanish speakers, however, never use the zh sound in such words.)

W is a letter that is not used much in Spanish. Zapotec w is pronounced about like English w (as in we). Here is an example, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| w | wi | “guava” | [wii] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 11. (With Ana López Curiel.)

(For more about the pronunciation of Zapotec w, see section §2.4.5.)

The Zapotec y sound is pronounced about like an English y (as in you). Many Spanish speakers use about the same sound in words like yo “I”. Here is an example, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| y | yug | “yoke (for oxen)” | [yuug] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 12. (With Ana López Curiel.)

(As mentioned earlier, some Spanish speakers pronounce the Spanish letter y with the sound of Zapotec zh, like the s of English pleasure. This pronunciation of y is not used in Valley Zapotec.)

Zapotec y is often used in combination with other consonants, either before a vowel or at the end of a word. Here are some examples, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| y | syuda | “city” | [syudaa] |

| y | rmudy | “medicine” | [rmuudy] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 13. (With Ana López Curiel.)

Zapotec final y in words like rmudy is pronounced differently from English final y in words like city. It is more like a softening of the final consonant sound that precedes it. (You can hear the sound of this y most clearly when you add something onto the end of a word ending in y, as you’ll see later in this lesson.) Sometimes, also, you will hear something like another y sound before the consonant that precedes the final y.

Almost any Zapotec consonant can be followed by y at the end of a word. Zapotec n plus y sounds a lot like the Spanish letter ñ as in baño “bathroom”, or like English ny in canyon. Here is an example, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| y | Jwany | “Juan” | [Jwaany] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 14. (With Ana López Curiel.)

The words syuda, rmudy, and Jwany illustrate a surprising thing about Zapotec — Zapotec words may start with sequences of consonants (and letters) that would never be used together at the beginning of an English or Spanish word! Listen carefully to your teacher’s pronunciation of such words.

The Zapotec letter x represents a sound about like that usually written with the letter combination sh in English (as in ship). (The Zapotec x sound is not the same as the sound of English x in exit.) Here is an example, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| x | xman | “week” | [xmaan] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 15. (With Ana López Curiel).

This sound is not used by most speakers of Spanish, although some speakers use this sound in words that originally were borrowed into Spanish from Nahuatl, such as the name Mexica, or borrowings from English written with sh, such as show. Zapotec x is never pronounced like Spanish x in México “Mexico” or éxito “hit”.

2.4.4. Two special spellings. The Zapotec g sound is written as the letter combination gu when it comes before e or i. Here is an example, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| gu | rgui | “gets sour” | [rguii] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 16. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

The Zapotec letter g is never written before e or i. (You may feel that the r at the beginning of rgui sounds different from the r at the beginning of rmudy, or that these r sounds sound different in from one repetition to the next. Before another consonant, a Valley Zapotec r may sound like a Zapotec rr or, occasionally, more like an English r, as in a word like writer.)

The Zapotec letter combination qu is used instead of c before the sounds e or i. Here is an example, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| qu | quizh | “will pay” | [quiizh] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 17. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

Qu represents exactly the same sound as c, but that letter is not used before e or i. (Zapotec qu is never pronounced like English qu in quick.)

These two special spellings in Valley Zapotec follow rules that are used regularly in Spanish, and occasionally in English. The spellings gu and qu are also used before the vowel letter ë, which you’ll learn about in section §2.5.

2.4.5 Two special pronunciations. Zapotec w and y are pronounced in an unexpected way when they appear at the beginning of a word before a consonant. In such words, w sounds a lot like a Zapotec u sound, and y sounds a lot like a Zapotec i. Here are two examples, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| w | wzhyar | “spoon” | [wzhyaar] |

| y | yzhi | “tomorrow” | [yzhii] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 18. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

2.4.6 Two more letter combinations. There are two additional Zapotec letter combinations that represent sound combinations that occur in both English and Spanish.

The letter combination ng can be pronounced in two ways in Zapotec. At the beginning of a word or in the middle of a word it is pronounced roughly like English ng in finger or like Spanish ng in mango “mango”. Here’s an example, which you can hear in the video below:

| ng | ngui | “sour” | [nguii] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 19. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

This is somewhat like an n sound followed by a g sound.

At the end of a word, ng may be pronounced the same as the beginning ng sound, or it may be pronounced without the g part of this sound — similar to the ng sound in English singer. (This second, end-of-the-word pronunciation of ng is not used by all speakers of Spanish, though some use it for some n sounds at the end of a word, as in the common Oaxacan Spanish pronunciation of jardín “garden”.) An example of ng at the end of a word will be presented in the next section.

The letter combination ts represents a sequence of the sound t followed by the sound s, roughly as in English cats. The same sound sequence is often spelled tz in Spanish, as in the name Maritza. The difference between English and Spanish, on the one hand, and Zapotec, on the other, however, is that Zapotec ts is a letter combination representing a single sound (somewhat like ch), while English t+s and Spanish t+z are two separate sounds. Examples of Zapotec words containing ts will be presented in the next lesson.

§2.5. The sixth Zapotec vowel sound — and the ending -ëng

All the examples so far have used only the five Zapotec vowels that are similar to the vowels of Spanish (with counterparts in English). However, there is another Zapotec vowel, ë (written as e with two dots, a special type of accent mark). This vowel, which is not used in either English or Spanish, is made somewhat like an u sound pronounced with the lips spread (as if you were saying i). The best way to learn to pronounce the Valley Zapotec ë sound, of course, is to listen to a native speaker and to practice!

Here’s an example of this vowel sound, which you can hear in the video that follows:

| ë | xdadëng | “his dice” | [x:daadëng] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 20. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

This word illustrates something interesting about Zapotec word structure. Earlier in this lesson you saw the word dad “dice” [daad]. In English, we need two words to say “his dice, her dice” (the dice he or she owns), but in Zapotec this can be expressed with one word. words (referring to things someone owns or has) begin with a x-. (A prefix is an element that is added to the front of a word to form a new kind of word. An English example is un-, as in unable. Prefixes are not words themselves and cannot be used on their own.) The (the person who owns or has the possessed item) goes after the word for that item. In xdadëng the possessor is expressed with an , -ëng. (An ending is an element that is added to the end of a word to form a new word, as with English -ed, as in kissed. Like a prefix, an ending is not a word itself and cannot be used on its own.)

Most likely the owner xtadëng is either nearby or is someone you know well. You’ll learn more about possessive expressions in Lecsyony Tsëda.

Here’s another example of the use of the ending -ëng, which you can hear in the video that follows:

|

Rmudyëng. |

“It is medicine.” |

[rmuudyëng] |

VLecsyony Tyop, Video 21. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

This example shows that a Valley Zapotec sentence can consist of a single word. This sentence is formed by adding the same ending -ëng that is used to mean “his” (or “hers” or, in fact, “its”) in the word xdadëng onto the word rmudy “medicine”. In the new example, -ëng means “it” (referring to something nearby). You’ll begin learning more about other ways to use the -ëng ending in Lecsyony Gaz.

Some Valley Zapotec speakers use the vowel ë in only a few words that don’t have endings like -ëng. For other speakers, however, this sixth Zapotec vowel is much more common. They use ë in place of e in many words, as you’ll learn in the next lesson.

§2.6. Diphthongs

In addition to simple vowels, Zapotec syllables can also contain diphthongs. A is a sequence of two different vowels (vowels written with different letters) in the same syllable.

There are six Valley Zapotec vowels — a, e, ë, i, o, and u — but not all possible combinations of these are used as diphthongs. The ten Valley Zapotec diphthongs are ai, au, ei, eu, ëi, ëa, ia, ie, ua, and ui. Not all speakers use all these diphthongs, and diphthongs are one of the areas where there is most variability in Valley Zapotec pronunciation. Your teacher may use different pronunciations from those that are written in this book, and you should follow your teacher’s pronunciation in deciding how to write diphthongs that you hear.

Here are some examples of words with diphthongs:

| ia | badia | “roadrunner” | [badiia] |

| ie | bied | “aunt” | [biied] |

| ua | bangual | “old person” | [bangual] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 22. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

You’ll learn more examples of diphthongs soon.

Only the diphthongs listed above are used in non-borrowed Valley Zapotec words. However, other diphthongs — such as ae, ea, eo, and oi — are used in words that originally came from Spanish. Here is an example:

| eo | Leony | “Leon” | [Leoony] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 23. (With Geraldina López Curiel.)

§2.7. More About Writing and Pronunciation

You’ve now learned everything you need to know about writing and spelling Zapotec with the system presented in this book! You will need to practice these skills, but you’ll find that writing Zapotec words that you hear will not be too hard, and that you’ll do even better with practice. In the next lesson, you’ll learn more about using pronunciation guides for reference if you need help remembering how to pronounce a word.

You haven’t yet heard all the different varieties of Zapotec sounds, however, especially the vowel sounds. Unlike English and Spanish vowels, Zapotec vowels may be produced in more than one way in terms of their — the way in which the air from the lungs is expelled through the glottis (the opening between the vocal cords at the top of the larynx) while the speaker makes the vowel. All English and Spanish vowels, as well as the Zapotec vowels we’ve discussed so far, are plain or “modal” vowels. Zapotec has three other types of vowels, however: breathy vowels, checked vowels, and creaky vowels, all of which are explained in Lecsyony Chon. The best way to learn to make these other types of vowels, and their various combinations, is to imitate your teacher’s pronunciation. If you forget how to pronounce a given word, you can always check the pronunciation guide for that word.

You’ll learn more about pronouncing Zapotec and using pronunciation guides in the next lesson, which will also give some more hints on how to use this writing guide.

§2.8. Zapotec alphabetical order

The alphabetical order we use in this book for Valley Zapotec (for instance, in the vocabulary at the end of this book) is like that you’re familiar with from English, except that letter combinations (such as ch and zh) are alphabetized separately. Here is the alphabetical order we’ll follow: a, b, c, ch, d, e, ë, f, g, i, j, l, m, n, o, p, qu, r, rr, s, t, ts, u, w, x, y, z, zh. Traditionally, Zapotec speakers don’t worry about spelling, so the letters we are using to write Zapotec don’t have Zapotec names. Therefore, when you are spelling Zapotec words, you can pronounce the names of the letters in English. (If you were using this book in Mexico, you’d probably want to pronounce the names of the letters in Spanish!)

§2.9. Reference Chart of Zapotec Spelling and Pronunciation

The chart below and on the next page gives the letters of the Zapotec alphabet with comparisons to pronunciations in English and Spanish, examples, meaning, and pronunciation, as introduced in this lesson (some sounds aren’t covered till Lecsyony Chon).

| comparison pronunciations | example | meaning | pronuciation | |

| a | roughly as in English father, Spanish amo | syuda | “city” | [syudaa] |

| b | roughly as in Spanish | Bed | “Pedro” | [Beed] |

| c | roughly as in English car, Spanish casa | capi | “shrine” | [capii] |

| ch | roughly as in English or Spanish | Chan | “Feliciano” | [Chaan] |

| d | roughly as in Spanish | dad | “dice” | [daad] |

| e | roughly as in English bet, Spanish peso | cafe | “coffee” | [cafee] |

| ë | doesn’t occur in English or Spanish (pronounced like the u of hula said with the lips spread) | xdadëng | “his dice” | [x:daadëng] |

| f | roughly as in English or Spanish | cafe | “coffee” | [cafee] |

| g | roughly as in Spanish | gan | “gain” | [gaan] |

| gu | used instead of g before e, i, or ë | rgui | “gets sour” | [rguii] |

| i | roughly as in English police, Spanish amigo | wi | “guava” | [wii] |

| j | roughly as in Spanish | jug | “juice” | [juug] |

| l | roughly as in English or Spanish | lechu | “lettuce” | [lechuu] |

| m | roughly as in English or Spanish | mon | “doll” | [moon] |

| n | roughly as in English or Spanish | canel | “cinnamon” | [caneel] |

| ng | roughly as in English finger, Spanish mango | ngui | “sour” | [nguii] |

| o | roughly as in English rodeo, Spanish hola | mon | “doll” | [moon] |

| p | roughly as in English or Spanish | plati | “cymbals” | [platii] |

| qu | used instead of c before e, i, or ë | quizh | “will pay” | [quiizh] |

| r | roughly as in Spanish (or like English t in city) | ri | “are around” | [rii] |

| rr | roughly as in Spanish | rran | “frog” | [rraan] |

| s | roughly as in English or Spanish | solisitu | “application” | [solisituu] |

| t | roughly as in English or Spanish | Tan | “Cayetano” | [Taan] |

| ts | roughly as in English | (discussed in Lecsyony Chon) | ||

| u | roughly as in English hula, Spanish luna | zu | “is standing” | [zuu] |

| w | roughly as in English | wi | “guava” | [wii] |

| x | roughly like English sh in ship | xman | “week” | [xmaan] |

| y | roughly as in English you | yug | “yoke (for oxen)” | [yuug] |

| z | roughly as in English | zu | “is standing” | [zuu] |

| zh | roughly like English s in pleasure | zhar | “vase” | [zhaar] |

Lecsyony Tyop, Video 24.

The form which shows how the Valley Zapotec word is pronounced. The pronunciation guide is always written in square brackets.

A mark written over a VOWEL letter, such as a GRAVE ACCENT [à], an ACUTE ACCENT [á], or a CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT [ê]. Normally, accents are used only in PRONUNCIATION GUIDEs. The two dots over the letter ë are a special type of accent mark; this letter, with its two dots, is used in ordinary Zapotec spelling.

A sound made with your mouth open and a continuous stream of air coming out without any obstruction.

A sound made with the stream of air coming from the lungs interrupted at some point by contact or constriction between the tongue and some other part of the mouth, between the two lips, or between other speech organs.

A rhythmic unit in a word. There are two types of syllables in Zapotec words: SIMPLE SYLLABLES and DIPHTHONG SYLLABLES. See also DIPHTHONG SYLLABLE, KEY SYLLABLE, SIMPLE SYLLABLE.

A SYLLABLE containing just one VOWEL.

At the end of the word.

A sequence of two letters that represents a single sound.

Belonging to someone.

An element that is added to the front of a word to form a new kind of word. An English example is un-, as in unable. Prefixes cannot be used on their own, but must be attached to another word.

The person (or thing) who owns or has an item.

An element that is added to the end of a word to form a new word, as with English ed, as in kissed. Like a PREFIX, an ending cannot be used on its own, but rather must be attached to another word.

A sequence of two different VOWELS (vowels written with different letters) in the same SYLLABLE.

The way in which the air from the lungs is expelled through the glottis (the opening between the vocal cords at the top of the larynx) while a speaker makes a VOWEL. Different phonations make the difference between Zapotec PLAIN, BREATHY, CREAKY, and CHECKED vowels.