1. Lecsyony Teiby: An Introduction to Zapotec

This course is designed to give you a working command of Valley Zapotec, an of Oaxaca, Mexico, spoken by many immigrants to California. The course presents a new simplified system for writing Valley Zapotec with a guide to pronunciation. In this first lesson (Lecsyony Teiby, or Lesson One) you’ll learn some background about the Zapotec people and their language.

In this book, new terms will be presented in CAPITALS. These are defined on the same page in which they are introduced, usually in the same paragraph. If you forget what any term means, however, you can check it in the glossary at the end of the book. Zapotec words used in the text are written in boldface. Your teacher will pronounce these words for you, and you’ll learn more about reading and pronouncing Zapotec beginning in the next lesson and continuing through this unida, or unit. Lessons and other sections in this unit do not include tarea (exercises) or specific ra dizh (vocabulary words) for you to learn, but these are included for all lessons beginning with Lecsyony Gai in Unida Tyop.

Section §1.1 presents an overview of Indigenous people of the Americas and their languages, section §1.2 an overview of the Zapotec language family, and section §1.3 an overview of Valley Zapotec. Section §1.4 describes the connections between Zapotec and Spanish, and section §1.5 explains the name Cali Chiu.

§1.1. Indigenous people and languages

The languages spoken by the inhabitants of North, Central, and South America before European contact and settlement are known as Indigenous languages of the Americas. In the United States, such languages are known as American Indian or Native American languages, but these names are not generally used for languages of other areas. In Canada, Indigenous languages are called First Nations languages. In Mexico and other parts of Latin America, they are generally referred to simply as Indigenous languages. The name “Indian” is not usually used to refer to Indigenous languages or people of Latin America, largely because of the highly negative connotations of the Spanish word indio, reflecting the prejudice against Indigenous people among some groups in Mexico and elsewhere.

At the time of first European contact, there were many hundreds of different languages spoken in the Americas. Many of these languages are no longer spoken, and virtually all of them are , meaning that they are losing speakers more rapidly than they are gaining them.

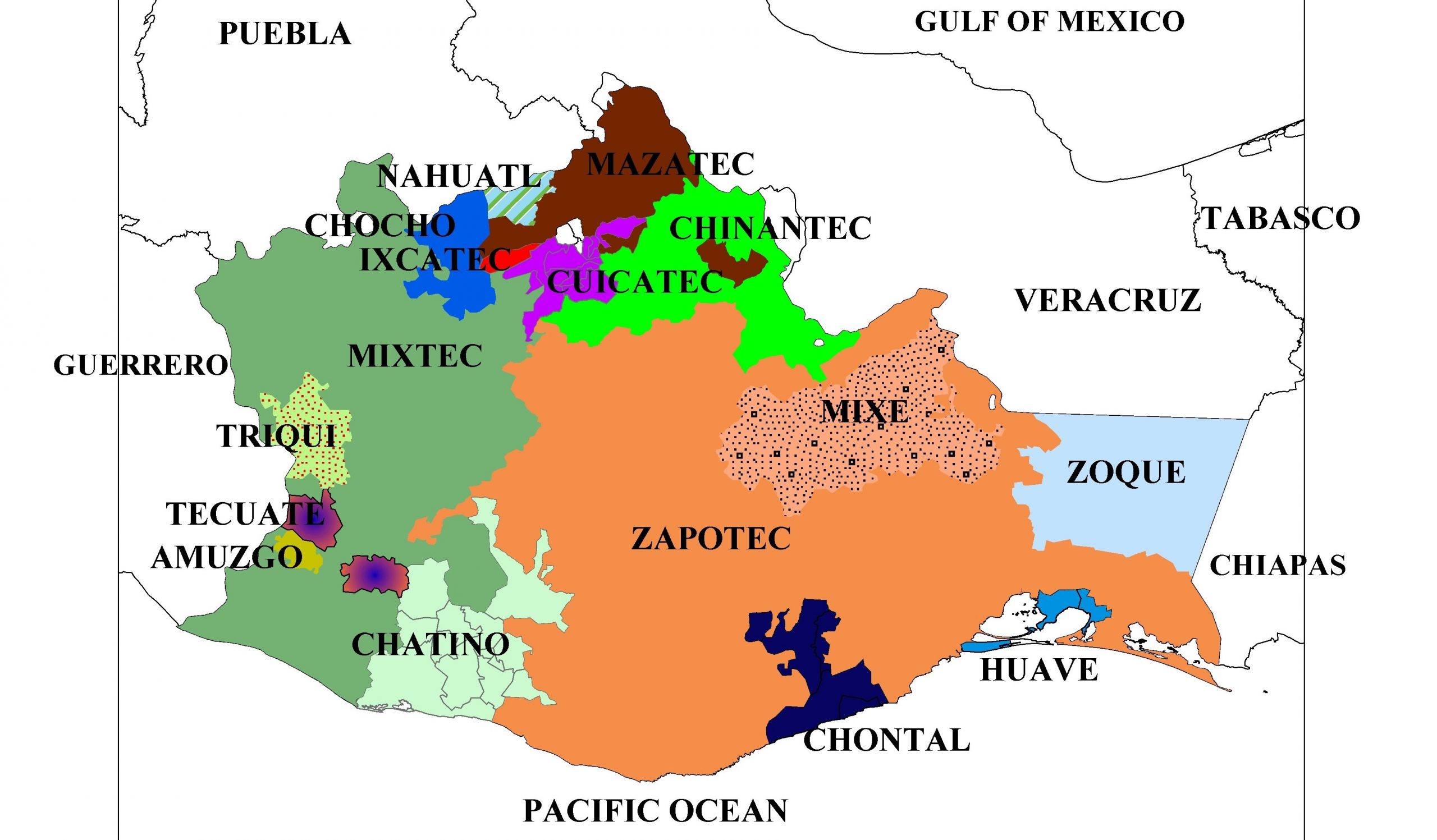

Mexico has more living Indigenous languages than the United States in a much smaller area. Today, the majority of Mexican Indigenous languages still in use are spoken in Oaxaca, a large southern Mexican state bordering the Pacific Ocean (see Map 1).

Lecsyony Teiby, Map 1. Mexico. The state of Oaxaca is in red.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Oaxaca_in_Mexico.svg

Oaxaca is one of the most linguistically diverse areas in the world. Almost all of the Oaxacan Indigenous language groups shown on Map 2 (on the next page) are not single languages but rather families, each containing from two or three to over 50 separate languages.

In the United States we usually think of ethnicity or race as genetically inherited, but in Mexico these concepts can be viewed more in terms of culture. A farmer from a small pueblo in Oaxaca who knows only a little Spanish probably would feel no hesitation in identifying himself as Indigenous — but how would his granddaughter who works in a Mexico City office and speaks only Spanish think of herself? Would she consider herself Indigenous? What about her parents, who may know some of an Indigenous language and choose not to use it? For some people in Mexico, Indigenous identity is closely related to knowledge of an Indigenous language, while for others it isn’t necessarily. This means that when an Indigenous language loses speakers, then, it is not only the language that is threatened, but also the cultural identity of that ethnic group.

By taking this course, you’re participating in preservation of an important aspect of the linguistic and cultural heritage of Mexico.

Lecsyony Teiby, Map 2. Indigenous language groups in Oaxaca.

Map by Felipe H. Lopez

§1.2. The Zapotec language family

Zapotec is a family of Indigenous languages of Mexico, most spoken in the state of Oaxaca, all of which can be called “Zapotec”. (This can be confusing! It means that two people may both say they speak Zapotec but not be able to understand each other at all.) There may be as many as 60 different languages in the family, though some scholars believe there are only a handful. The Zapotecs constitute one of the largest ethnic groups in Oaxaca.

Many people, including many speakers of Indigenous languages, use the word “dialect” (or the Spanish word dialecto) to refer to these and other Indigenous languages. This is a confusing term, since, technically speaking, are different varieties of the same language that speakers can differentiate, but which are still understandable — or — to each other. Thus, American English and British English are dialects of English, just as Mexican Spanish and Spanish as spoken in Spain are dialects of Spanish. (Actually, each of these four language varieties has a number of different identifiable sub-varieties, as you may be well aware.) But Valley Zapotec, the language spoken in the Tlacolula Valley of Oaxaca and the subject of this course, is a completely different language from any variety of Zapotec spoken in the Sierra of Oaxaca, in Southern Oaxaca, or in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, as well as from several other languages of central Oaxaca — these are not “dialects” of Zapotec at all, but totally different languages.

The table below shows some fairly closely related words in six Zapotec languages, Macuiltianguis Zapotec (SPMZ, from San Pablo Macuiltianguis in the Sierra Juárez region of Oaxaca), Zoogocho Zapotec (SBZZ, from San Bartolomé Zoogocho in the Villa Alta region of Oaxaca), Zaniza Zapotec (SMZZ, from Santa María Zaniza in the Sola de Vega region of Oaxaca), Dihidx Bilyáhab (SDAZ, from Santo Domingo Albarradas in the mountains of the Tlacolula district northeast of Tlacolula), Mitla Zapotec (MZ, from San Pablo Villa de Mitla, less than fifteen kilometers east of Tlacolula), and Valley Zapotec, the subject of this course (represented here by the variety spoken in San Lucas Quiaviní, SLQZ). (The Valley Zapotec words are given in the spelling system used in this book, with pronunciation guides — explained later in this unit — in brackets.) Mitla Zapotec and Dihidx Bilyáhab are the languages most similar to Valley Zapotec, but you can see that there are similarities and differences between any two of these languages — and these are only six of perhaps 50 different Zapotec languages!

| SPMZ | SBZZ | SMZZ | SDAZ | MZ | SLQZ | |

| mushroom | be’yá | bi’a | bé’y | be’ | be [be’eh] |

|

| meat | beelá’ | bela’ | bál | behél | bääl | bel [beèe’l] |

| snake | bèllà | bel | bíly | behel | bäl | bel [bèèe’ll] |

| fish | béllá | bel | bal | bejel | bäjl | bel [behll] |

| man’s brother | bettsi’ | bishe’ | bity | bíjch | bejtz | bets [behts] |

| foam | besiina’ | bzhina’ | bidxiny | bitzun | btseny [btsehnny] |

|

| nopal | beyàá | bia | biyá | bíyahá | biaa | bya [byàa] |

| man’s sister | dàànà | zan | zan | zan | bisiajn | bzyan [bzyaàa’n] |

| forehead | yhigáá | lhoxga | tiga | lukwaj | locuaj | locwa [lohcwah] |

| knee | yhííbi | xib | ij-tyíb | gya-a zhib | yecxhijb | zhiby [zhihihby] |

You may wonder why we cannot give a more precise figure for the number of Zapotec languages. The reason is that these languages are for the most part not well described — most of them have no dictionaries, no grammar books, and no standard written form. Deciding whether two groups of speakers speak one language or two is a tricky matter. For most linguists, the decision depends on mutual intelligibility, whether the two groups of speakers can understand each other when they talk. Measuring mutual intelligibility is difficult, however, and not everyone agrees on how it should be done, which explains the disagreement about the number of Zapotec languages.

The Zapotecan family of languages is included in a large group of related Indigenous languages called Otomanguean, which includes such groups as Chatino, Mixtec, Chinantec, and many others, most spoken in southern Mexico. The Otomanguean languages may be distantly related to other Indigenous languages of the Americas, but they are not connected with Spanish, English, or any other European language.

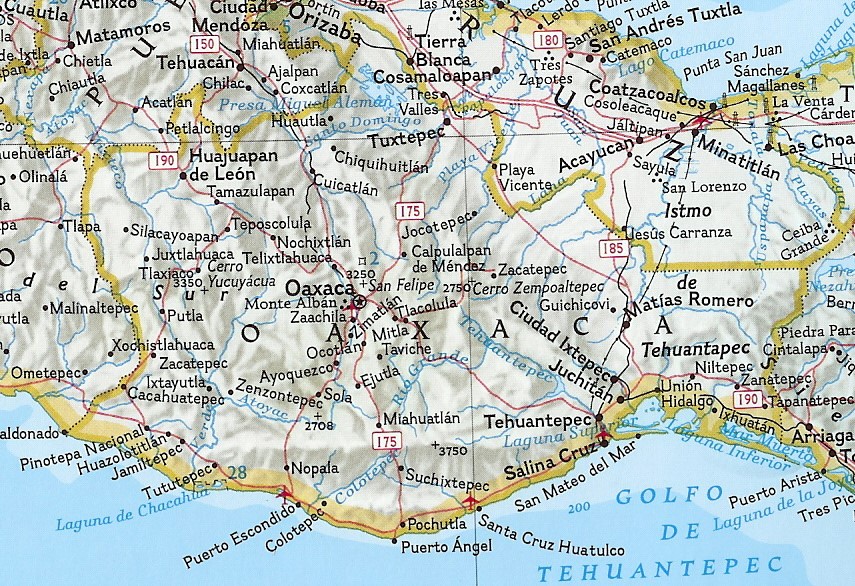

Lecsyony Teiby, Map 3. Oaxaca state. The city of Oaxaca de Juárez (known as Oaxaca City in English) is in the middle; Tlacolula de Matamoros is to its southeast.

National Geographic Society. 1999. Atlas of the World. Seventh Edition. National Geographic: Washington, D.C.

§1.3. Valley Zapotec

Valley Zapotec is the Zapotec language spoken around the town of Tlacolula de Matamoros (normally called just “Tlacolula”) southeast of Oaxaca City in the central part of Oaxaca state (Map 3), in the Tlacolula Valley, the northwestern part of the Tlacolula District (a political division of Oaxaca state analogous to an American county, of which Tlacolula is the cabecera or county seat). (Cabecera is a Spanish word. For more about the use of Spanish words in this book, see section §1.4 at the end of this lesson.) More precisely, this language might be called Tlacolula Valley Zapotec, or even Western Tlacolula Valley Zapotec, since other languages are spoken in the Valley of Oaxaca and the Tlacolula District, but we will use the name Valley Zapotec in this book.

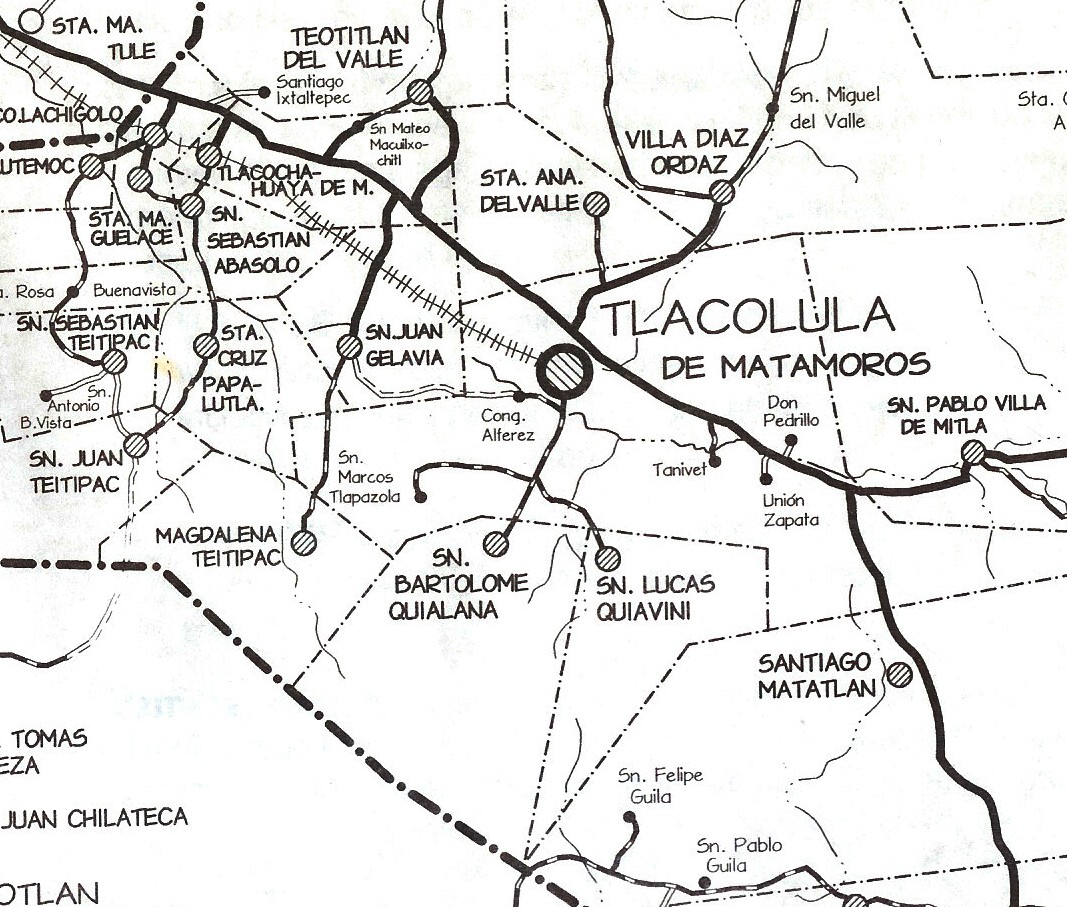

Valley Zapotec is spoken by people in at least 12 different pueblos (towns or villages) in the Tlacolula District, including San Miguel del Valle, Villa Diaz Ordaz, Santa Ana del Valle, Teotitlan del Valle, Tlacochahuaya, San Sebastián Abasolo, San Juan Teitipac, San Juan Guelavía, San Marcos Tlapazola, San Bartolomé Quialana, San Lucas Quiaviní, and Tlacolula itself. These pueblos are shown on Map 4, starting with San Miguel del Valle north of Tlacolula, and going counterclockwise. The heavy broken line near the bottom left corner of the map is the district boundary, while the lighter broken lines separate municipios or municipal political units.

Lecsyony Teiby, Map 4. Valley Zapotec pueblos around Tlacolula de Matamoros, northwest Tlacolula District, Oaxaca.

Map from Ángel García García, et al. n.d. [1998?]. Oaxaca: Distritos (Municipios, Localidades, y Habitantes). n.p. (Priv. de Rayon no. 104, Centro, Oaxaca, Oax.)

Additional Zapotec languages are spoken in other areas, including the pueblos of San Pablo Güilá, Santiago Matatlán, and San Pablo Villa de Mitla to the south and east of Tlacolula. The languages of these communities (and other Zapotec pueblos outside the area on the map) are largely mutually unintelligible with Valley Zapotec, though some speakers may well be able to understand each other to some degree.

Although all the Valley Zapotec pueblos speak Valley Zapotec, each pueblo has its own individual way of talking, and fluent speakers can easily tell the difference between different varieties of Valley Zapotec. In this course, we will focus on Valley Zapotec as it is spoken in San Lucas Quiaviní (which we’ll normally refer to as “San Lucas”) and Tlacolula.

Traditionally, the Valley Zapotec people have supported themselves through subsistence agriculture. Tlacolula, however, is a market town and has served as the commercial as well as political center of the region for centuries and has internet cafes, restaurants, and hotels, as well as the weekly Sunday market.

These differences are mirrored in the way the language is used. In Tlacolula de Matamoros, only a few dozen people over the age of 70 speak Zapotec, while in San Lucas the majority of people still speak the language, which is used in many aspects of daily life in the town (except in school, where instruction is in Spanish). The use of Zapotec in other Valley Zapotec pueblos varies between these two extremes.

People from the Tlacolula Valley have been coming to the United States to find work since the start of the Bracero Program in 1942: over half of the men of San Lucas, for example, have worked in the United States, and nearly everyone in the town has a relative working on the “other side” (north of the border). The money these people send back to Oaxaca makes a huge difference in the community. There are now many hundreds of speakers of Valley Zapotec in Los Angeles (and other parts of the United States).

§1.4 Zapotec and Spanish

The Valley Zapotec people first encountered Spanish soldiers and priests in the 1580s. Since the conquest of Mexico, Valley Zapotecs have been in constant contact with Spanish speakers to differing degrees throughout the region. (Probably there has always been more contact in the district center of Tlacolula than in remote villages like San Lucas Quiaviní.)

Because of this long contact, all varieties of Zapotec borrow many words and longer expressions from Spanish (and the local variety of Spanish has been influenced by Zapotec as well). Some of these borrowed words (particularly those borrowed more recently) have not changed much in the borrowing process, and you will recognize many of these if you know Spanish. Other words, however (especially those borrowed longer ago), have changed considerably in both pronunciation and meaning. Even people fluent in both languages sometimes have trouble recognizing their connection.

What’s important to realize, however, is that Zapotec and Spanish are completely different languages. While a knowledge of Spanish will help you understand some loanwords (borrowed words) in Zapotec, it can be confusing at other times (since some words change their meaning during the borrowing process). You do not need to know Spanish to study Zapotec. For this reason, we will give translations for Spanish words we use in the course, even though these will seem completely unnecessary to some readers.

Many of the Zapotec words you’ll learn in this course can be best defined with Spanish words, however, since they refer to concepts and especially cultural items for which there is no English word. Spanish words used in Zapotec sentences and readings will be written in italics.

§1.5. Why Cali Chiu?

Cali chiu? means “Where are you going?” in Valley Zapotec. This is not only a useful question to be familiar with, but is also an important greeting used between friends and acquaintances when they meet on the street. (S-4 presents more greetings that you should learn.)

Even some people from Tlacolula who don’t speak Zapotec are familiar with this phrase, because cali chiu was also used as a local name for the bicycle taxis that were used as transportation in Tlacolula and several other communities in Oaxaca (pictured on the title page of this book). Today motorcycle taxis (like the one shown in Picture 1 below) have now replaced them.

Lecsyony Teiby, Picture 1. A motorcycle taxi in Tlacolula.

A language spoken by the inhabitants of an area before any outside contact.

A language which is losing speakers more rapidly than it is gaining them.

A distinct variety of a language. Typically, speakers of one dialect can differentiate other varieties, but they are all still understandable – or MUTUALLY INTELLIGIBLE – with each other.

Understandable to each other (a characteristic of two speech varieties whose speakers can understand each other when they talk).