21. Lecsyony Galyabteiby: Rida Liaza! “Come to My House!”

Section §21.1 gives the verb ried “comes”, and sections §21.2 and §21.3 two related topics, bringing and taking verbs, and venitive “comes and” verbs. Sections §21.4 explains references to locations around the house. The incompletive forms of ria “goes” and ried “comes” are introduced in section §21.5. Section §21.6 describes new ways to use numbers, and section §21.7 presents reverential pronouns.

Ra Dizh

angle [a’nngle’eh] angel

antes de [á’nntehs deh] before (in time)

beu [be’èu] moon

blidguiny [bli’dguìiny] mosquito

bzicy ni rnudizh … cuan Dizhsa! [bzi’ihcy nih rnudìi’zh … cuahnn Dìi’zhsah!] return (tell) what …. asks in Zapotec!, answer the questions in … in Zapotec! (as in bzicy ni rnudizh Part Teiby cuan Dizhsa! “answer the questions in Part Teiby in Zapotec!”)

ca [càa’ah] has, is holding § neut. of rca; coo [coo’-òo’] “you have”

cweyu [cwe’yu’uh] beside the house

Dadbied [Dadbied] holy, blessed (title used before the name of a male saint or holy person)

detsyu [dehtsyu’uh] behind the house

duzh [dùu’zh] some, a few, a little

guecyu [gue’ehcyu’uh] 1. roof of a house; 2. on the top of the house, on the roof of the house

lainy [làa’-ihny] he, she, it, him, her (rev.)

lanyu [làa’nyu’uh] in the house

lariny [làa’rihny] they, them (rev.)

loyu [lohyu’uh] in the area in front of the house, but not directly in front of the door, and very likely farther away than ruyu

Luny [Luuny] Monday

nai [nài’] yesterday

Nambied [Nnambied] holy, blessed (title used before the name of a female saint or holy person)

nax [nnahx] chocolate; hot chocolate

niebagli [ni’ebaglii] / niebagui [ni’ebaguii] that’s why

Nort [No’rt] the North; the United States

raisy [ra’ihsy] sleeps § perf. btaisy; irr. gaisy [ga’isy]

rbez [rbèez] 1. sits; 2. lives; 3. is at home (form. verb) (same as rbez “waits”)

rca [rcaa’ah] 1. gets; takes; 2. (used to express a recipient object; see lesson) (CB verb) § irr. yca; perf. cwa; neut. ca “has, is holding”; coo [coo’-òo’] “you took” (perf.), “you have” (neut.)

rcuya [rcu’yàa’ah] / rlaya [rla’yàa’ah] pushes

rcwats [rcwàa’ts] buries; hides (something)

rdiby [rdi’ìi’by] ties (something) onto (something) § prog. candiby [candìi’by], caldiby [caldìi’by]

rdyeny [rdyehnny] 1. rises (of the sun); 2. sprouts, comes up (of a plant) § irr. ndyeny [ndyehnny], indyeny [indyehnny]

rga [rga’ah] pours § prog. prog. canda [canda’ah] / calda [calda’ah]

rguty [rguhty] kills

rgya [rgyàa’ah] dances

rgwi cuan [rgwi’ih cu’an] visits > rgwi

ri [rii] 1. are around, are there, are located in (a location) (plural living subject); 2. is around, is there, is located in, is spread around in (a location) (mass non-living subject) (neut.; no hab.) § perf. bri [brih] / wri [wrih]; irr. cwi [cwii]; no prog.;”we” subj. forms use base zhu [zhu’]: neut. zhuën [zhu’-ëhnn], perf. bzhuën; irr. yzhuën

ried [rìe’d] comes § perf. bied; irr. gyied; “I” subject base –yal [yàa’ll]; “we” subject base –yop [yoo’p] (see lesson); imp. rida [ridàa’]

riedgwi cuan [rìe’dgwi’ih cu’an] comes and visits (ven. of rgwi cuan)

riedne [rìe’dnèe] / ridne [ri’dnèe] brings (see lesson) § perf. biedne; irr. gyiedne (see lesson) > ried, –ne

rine [rinèe] takes (see lesson) § perf. gune; irr. chine > -ne

rla [rlàa] bumps into, hits against; attacks (of a turkey)

rlaya [rla’yàa’ah] pushes (see rcuya)

rtyug [rtyùu’g] cuts; slices

ruxna [ru’x:nnaàa’] gets married; marries (someone) § perf. buxna; irr. guxna > na “hand”

ruyu [ru’yu’uh] 1. doorway of a house; 2. in front of the house, in the doorway of the house

rragueli [rraguèe’llih] it is the next day

rreizh [rree’ihzh] calls § irr. cuzh [cuuzh]; prog. cabuzh [cabu’uhuhzh]

San Luc [Sann Lu’uc] Saint Luke, San Lucas

wbizh [wbi’ihzh] / wbwizh [wbwi’ihzh] / wwizh [wwi’ihzh] sun

Xandan [Xanndaan] 1. Saint Anne, Santa Ana; 2. Santa Ana del Valle

xtadmam [x:ta’adma’mm] grandfather (e-poss. only)

xnanmam [x:nna’anma’mm] grandmother (e-poss. only)

ydapta [yda’pta’] the four of

ygyonta [ygyòonnta’] / gyonta [gyòonnta’] the three of

yropta [yro’pta’] / ropta [ro’pta’] the two of, both of

ze [zèe] was going (inc. of ria “goes” — see lesson)

zied [ziìe’d] was coming (inc. of ried — see lesson)

Xiëru Zalo Ra Dizh

1. You already know that rbez means “waits”. But the new meanings of rbez work like the other formal verbs you learned in Lecsyony Tseinyabteby. With these meanings, rbez can only be used with formal subjects or subjects you’d address with a formal “you”. The only subject pronouns that can be used with rbez are formal pronouns, respectful pronouns, or the new reverential pronouns you’ll learn in this lesson.

2. Ruxna “marries” includes the word na “hand”. When you use a bound pronoun as the subject of this verb, the combination is pronounced just like “hand” with a bound pronoun possessor. (Zapotec has many verbs like this that include “incorporated” body parts.)

3. Riedgwi cuan “comes and visits” is a complex venitive verb based on rgwi “looks” (see section §21.3). Its object is marked with a bound pronoun following cuan (the word for “where is”).

4. Rragueli means “it is the next day”. This time expression is commonly used in past time expressions like chi bragueli “(when it was) the next day”.

5. Luny “Monday” is one of the new time words you’ll learn more about in the supplement on telling time, section S–25.

6. Ri is used with two different types of subjects. A subject of ri referring to a living creature must be plural. But ri is also used with MASS NOUN subjects. A mass noun is a non-living item that can’t be counted, usually a substance like “water” or “sand” or “money”. Here are examples of these two uses of ri:

|

Ra buny ri ricy. |

“The people are there.” |

|

Nyis ri re. |

“The water is here.”, “There is water here.” |

Ri is an unusual verb. Although it starts with r, it is a neutral verb rather than a habitual one (there is no separate habitual, though). “We” subjects of ri use the base zhu [zhu’]: thus, “we are” is zhuën [zhu’-ëhnn]. Although the normal irrealis and perfective stems of ri are irregular, “we” forms use regular prefixes: “we will be” is yzhuën, and “we were” is bzhuën.

7. Both rap and ca mean “has”. The difference between these is that rap is used more generally and can be appropriate any time a subject has something in his or her possession, while ca usually means that the subject is actually holding the item.

§21.1. Ried “comes”

Using ried “comes”. The verb ried [rìe’d] “comes” is a useful — but very irregular! — Zapotec verb. Here are some simple sentences containing ried:

|

Ried ra mna antes de ra nguiu. |

“The women come before the men.” |

|

Riedrazh na. |

“They are coming now.” |

|

Chi ried xtada liazën, riedneëb serbes. |

“When my father comes to our house, he brings beer.” |

Like ria “goes” (Lecsyony Tseinyabtyop), ried does not have a regular progressive form starting with ca-, so its habitual can sometimes express a progressive -ing meaning, as in the second sentence above. Note also that (again like ria) you don’t need to use “to” to specify the location someone comes to.

The perfective stem of ried is bied, and the irrealis is gyied.

|

Gyiedu e? |

“Are you going to come?” |

|

Bied xtadmama Nort lo 1978. |

“My grandfather came to the United States in 1978.” |

|

Rcaz Jwany gyied Ndua. |

“Juan wants to come to Oaxaca.” |

The last example is a plural command, using the irrealis form, as you’d expect. However, ried has an irregular imperative, rida [ridàa’]. The perfective bied is not used in imperatives.

|

Rida re! |

“Come here!” |

Surprisingly, the imperative form rida is also used in plural and formal commands. (As you know, this isn’t possible with ordinary perfective imperatives.)

|

Ual rida re! |

“Come here (you all)!” |

|

Ridala re! |

“Come here [form.]!” |

“Comes” with “I” and “we” subjects. The most irregular thing about ried is the way it works with “I” and “we” subjects. Unlike all other Zapotec verbs, ried changes its base in every stem for “I” and “we” subjects!

**The “I” base for “come” is yal [yàa’ll]. Here are some examples:

|

Ryala rata zhi. |

“I come every day.” |

|

Byala Nort lo 2002. |

“I came to the United States in 2002.” |

|

Rcaza gyala liazu. |

“I want to come to your house.” |

Although the base is different, in other ways these “I” forms of “comes” work just like ried, except that the base yal is always used with the bound pronoun -a “I”. The perfective stem for an “I” subject is byal, and the irrealis base for an “I” subject is gyal.

The “we” base for “come” is yop [yoo’p]. Again, otherwise this base works just like ried, except that the base yop is always used with the bound pronoun -ën “we”:

|

Ryopën re rata zhi. |

“We come here every day.” |

|

Byopën re Luny. |

“We came here on Monday.” |

|

Gyopën ydo. |

“We are going to come to church.” |

Although the base is different, in other ways these “we” forms of “comes” work just like ried, except that the base yop is always used with the bound pronoun -ën “we”. The perfective stem for a “we” subject is byop, and the irrealis base for a “we” subject is gyop.

Fot Teiby xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby. The church in Tlacolula.

Fot Teiby xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby. The church in Tlacolula.

Using the “come” bases with particles. Here are some negative “comes” sentences:

|

Queity rieddi Jwany liaza rata ra zhi. |

“Juan doesn’t come to my house every day.” |

|

Queity byaldya liazu. |

“I didn’t come to your house.” |

|

Queity byopdyën ydo. |

“We didn’t come to the church.” |

In each case, the negative particle -di comes after the verb base, before the subject, just as you’d expect.

The same thing happens with the -zhyi “must” particle:

|

Riedzhyëng re rata zhi. |

“He must come here every day.” |

|

Queity byaldizhya liazu. |

“I must not have come to your house.” |

|

Queity byopdizhyën ydo. |

“We must not have come to the church.” |

Tarea Teiby xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

Part Teiby. Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. Did he come to your house?

b. Will they come to church?

c. Do you think you will come to Oaxaca?

d. Who came to the United States in 1999?

e. Who came to San Lucas yesterday?

f. Who will come to Santa Ana tomorrow?

g. Will they come here?

h. When did he come to Los Angeles?

i. Are you all coming here now?

j. Will you (form.) come tomorrow?

Part Tyop. Bzicy ni rnudizh Part Teiby cuan Dizhsa! (This means, “Return (tell) what Part Teiby asks in Zapotec!” or “Answer the questions in Part Teiby in Zapotec!”.)

Part Chon. Now, make up some new Zapotec sentences using the verb ried following the directions below. Add additional words (such as place names) to complete your sentences. Then translate your new sentences into English.

| subject | verb form | additional directions | |

| a. | “we” | habitual | |

| b. | “I” | perfective | use the particle –zhyi |

| c. | “Juana” | irrealis | make this a question |

| d. | “Ignacio” | habitual | make this sentence negative |

| e. | “we” | perfective | |

| f. | “my friend” | irrealis | make this sentence negative |

| g. | “the teachers” | habitual | |

| h. | perfective | make this an imperative | |

| i. | “I” | irrealis | use -zhyi |

| j. | “they” | habitual | make this a negative question |

§21.2. Bringing and taking

The Zapotec verbs for “takes” and “brings” are formed by adding the –ne “with” extender onto the verbs “goes” and “comes”. (In other words, when you go along with something, you take it, and when you come along with something, you bring it!)

“Takes” is rine [rinèe], with the short form of “goes” used in andative verbs. This verb combines with bound pronouns just the same way every other –ne verb does. The following forms have irregular pronunciations (as with any other –ne verb):

|

rinia [riniìa’] “I take” rineu [rinèu’] “you take” rineëng [rinèe’-ëng] “he (prox.) takes” rinei [rine’èi’] “he (dist.) takes” |

All the other forms of rine are regular combinations of the stem plus the appropriate pronouns. The perfective of rine is gune, and the irrealis is chine, as you would expect with andative verbs.

Most speakers use special andative prefixes on “we” subject forms of “takes”:

|

ryoneën [ryoo’nèe-ëhnn] “we take” byoneën [byoo’nèe-ëhnn] “we took” choneën [choo’nèe-ëhnn] “we will take” |

“Brings” riedne [rìe’dnèe] also includes –ne. But there’s a catch with this one, just as there is with the verb ried. Here are the forms of “brings” that are irregular in spelling or pronunciation:

|

riednia [rìe’dniìa’] / ryalnia [ryàa’llniìa’] “I bring” riedneu [rìe’dnèu’] “you bring” riedneëng [rìe’dnèe’-ëng] “he (prox.) brings” riednei [rìe’dne’èi’] “he (dist.) brings” ryopneën [ryòo’pnèe-ëhnn] “we bring” |

As you can see, some of these forms use the regular “comes” base ied with the –ne extender, but some, just as with the verb “comes”, have special bases. With an “I” subject, most speakers use the regular base, but some use the special “I come” base yal plus –ne. With a “we” subject, you’ll generally hear only the special “we come” base yop plus –ne. (It’s likely that some speakers may use the regular form riedne for “we” subjects too, but we will not use that in this book.) All the other forms of riedne are regular.

In the perfective, “brought” is biedne. “I brought” can be either biednia or byalnia, and “we brought” is byopneën. In the irrealis, “will bring” is gyiedne. “I will bring” can be either gyiednia or gyalnia; “we will bring” is gyopneën.

Here are some sentences using riedne and rine:

|

Gune Lia Tyen liebr scwel. |

“Cristina took the book to school.” |

|

Gyiedne doctor rmudy liazën. |

“The doctor will bring the medicine to our house.” |

|

Riednia guet re rata zhi. |

“I bring tortillas here every day.” |

As these examples show, you can add a location following the object in a “brings” or “takes” sentence. Just as in a “goes” or “comes” sentence, you don’t need a word for “to” with these sorts of locations.

Tarea Tyop xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

Part Teiby. Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. Will you take these blankets to your aunt’s house?

b. What did he bring to the church?

c. Who brought these apples?

d. When should I bring the money to the church?

e. Did you (form.) bring meat to my mother’s house?

f. Did you all bring your books?

g. Why did he take a chair to the field?

h. Do you want to take my pots to the market?

i. Who will take the flowers to church?

j. Does Juana take her brother to school every day?

k. Soledad will take the baskets to the market.

l. Take these tortillas to the restaurant now!

m. Gloria brought a cat to my house.

n. Ignacio didn’t bring a pen to school.

o. Bring the baby here!

Part Tyop. Bzicy ni rnudizh Part Teiby (a) – (j) cuan Dizhsa.

But what if you want to say something like Cristina took the book to the teacher? The “to” in this sentence is expressed quite differently in Zapotec than in English. Here are some examples:

|

Gune Lia Tyen liebr cwa mes. |

“Cristina took the book to the teacher.” |

|

Gyiedne doctor rmudy ycaën. |

“The doctor will bring the medicine to us.” |

|

Riednia guet rcaëb rata zhi. |

“I bring tortillas to him every day.” |

These sentences start with the “brings” or “takes” verb plus its subject and object. Following that, there is a form of the verb rca “gets”. The subject of rca expresses the recipient, the person (or, sometimes, thing) that gets the object that is brought or taken, the noun phrase, name, or pronoun we use after to in the English sentence. (Thus, these sentences mean something like “Cristina took the book, the teacher got (it)” — but notice that there is no word for “it”, so this is not exactly what these sentences say.) The form of the verb rca must match that of rine or riedne. In the first example, both verbs are perfective; in the second, both are irrealis, and in the third, both are habitual. Here’s the pattern:

| form of rine/riedne | subject | object | form of rca subject | |

| recipient object |

||||

| Gune | Lia Tyen | liebr | cwa | mes |

| Gyiedne | doctor | rmudy | yca | -ën |

| Riedni | -a | ra guet | rca | -ëb |

If you listen to Zapotec speakers, you’ll find that they use the rca recipient object pattern with other verbs in addition to rine and riedne.

English speakers often use bring and take in different ways than Zapotec speakers use riedne and rine. In particular, English speakers often use bring in ways that Zapotec speakers feel is inappropriate for riedne — you may feel that Cristina brought the book to school means about the same as Cristina took the book to school, but Zapotec speakers probably won’t agree. You may be corrected if you try to translate directly from English. Listen to speakers, and you’ll develop a better feeling for how to use these verbs.

Tarea Chon xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

Part Teiby. Change each of the following Zapotec sentences by adding the recipient objects in parentheses to the sentence, as in the example. Then translate your new sentences into English.

Example. Gune doctor rmudy. (Bied Lia Petr)

Answer. Gune doctor rmudy cwa Bied Lia Petr. “The doctor took the medicine to Señora Petra.”

a. Chineu libr re e? (estudian)

b. Gunia ra becw (her (prox.))

c. Xi gunei? (bxuaz)

d. Biedneu caj re e? (him (an.))

e. Gunei fruat. (them (dist.))

f. Biedne meser nax. (me)

g. Ryoneën gyia. (ra mes)

h. Rine betsa rregal. (Cristina)

i. Riednia guet rata zhi. (xnana)

j. Gyiednerëng ra budy ngual. (mardom)

k. Byopneën muly. (pristen)

l. Chine xbiedu ra guet e? (xnanmamu)

Part Tyop. Now create your own Zapotec sentences about “bringing” and “taking” the items pictured below. Use recipient objects in the sentences.

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

g.

h.

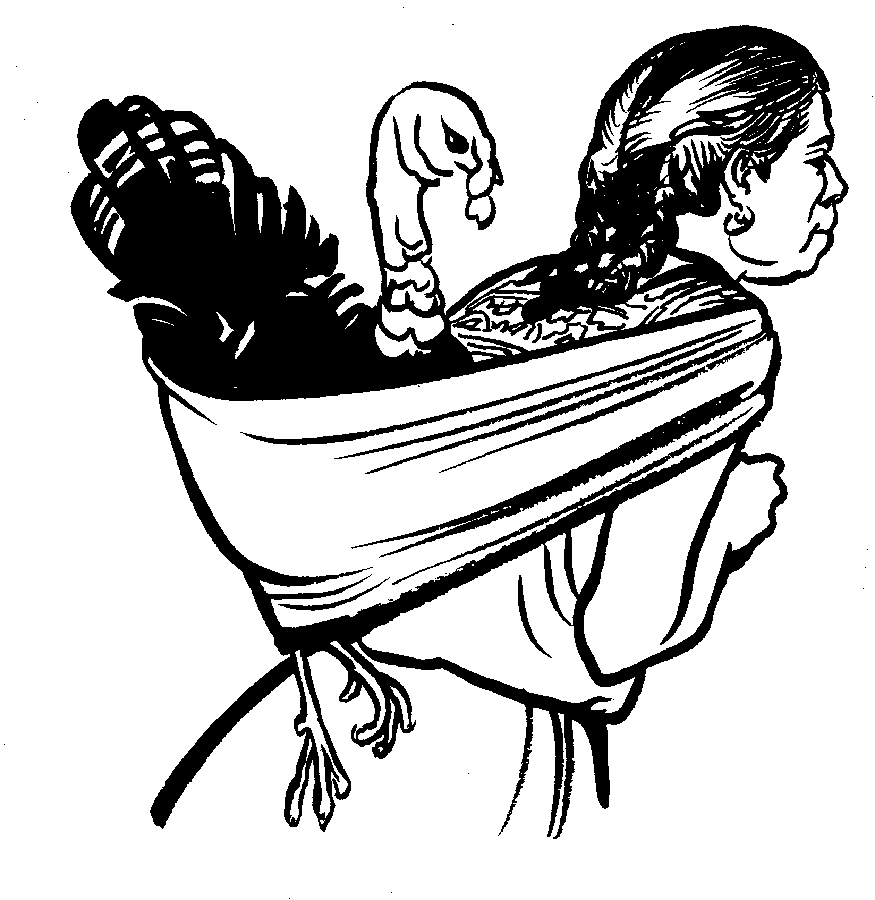

Part Chon. Consider the picture below and write a short story using the verbs “bring” and “take”. Think about where the woman might be going and why.

§21.3 Venitive “comes and” verbs

Venitive verbs. “Brings” looks like a group of “comes and” or VENITIVE verbs, which are similar to the andative verbs you learned about in Lecsyony Tseinyabtyop. Here are some examples:

|

Tu riedcwany bzyan Lia Len? |

“Who comes and wakes up Elena’s brother?” |

|

Rata zhi riedcwualëng rrady. |

“Every day he comes and turns on the radio.” |

|

Rata zhi riedtyug Lia Petr ra guia. |

“Petra comes and cuts flowers every day.” |

|

Riedcwats becw zuat. |

“The dog comes and buries the bone.” |

|

Riedcuyaëng naa rata zhi. |

“He comes and pushes me every day.” |

Habitual venitive verbs include ried- [rìe’d] or its short form rid- [ri’d] added at the front of a verb base. The bases are underlined in the ordinary and venitive examples below:

|

rtyug “cuts” |

riedtyug “comes and cuts” |

|

rreizh “calls” |

riedreizh “comes and calls” |

|

rcwats “buries” |

riedcwats “comes and buries” |

|

rcuya “pushes” |

riedcuya “comes and pushes” |

Most speakers alternate between using ried- or rid- on venitive verbs. In this book, we will write venitive verbs with ried-, but you will hear these verbs pronounced both ways. Follow your teacher’s usage (and you can write these verbs with rid- if you like).

Irrealis venitive verbs start with gyied- (short form gid-), and perfective venitive verbs start with bied- (short form bid-).

|

Gyiedtyug Lia Petr ra gyia. |

“Petra will come and cut flowers.” |

|

Biedtyug Lia Petr ra gia. |

“Petra came and cut flowers.” |

|

Gyiedgyaad. |

“You guys will come and dance.” |

|

Biedgyaad. |

“You guys came and danced.” |

Like the verb ried, venitive verbs have no regular progressive form starting with ca- (you’ll learn more about expressing progressives with these verbs in section §21.4).

Venitive verbs are used to say that someone comes and performs an action. They can be translated either with English “comes and” or, often, with “comes to”. While the “comes to” translation may sound better to you in some cases, there’s an important difference between English comes to (or will come to or came to) sentences and Zapotec venitive verbs. An English sentence like Petra came to cut the flowers does not necessarily mean that Petra actually cut the flowers (just that she came with the intention of doing so). However, the Zapotec sentence Biedtyug Lia Petr ra gyia means that Petra not only came, she also cut the flowers (as with English Petra came and cut the flowers). Another way to think of this is that the English sentence Petra came to cut the flowers primarily tells us about Petra’s coming. However, the Zapotec sentence Biedtyug Lia Petr ra gyia tells us about both coming and cutting.

Special venitive prefixes. Just as with ried, “I” and “we” subject forms of venitive verbs have special forms. While some speakers may use the ordinary venitive prefixes ried-, bied-, and gyied- with “I” subjects, others will use the special “I” venitive prefixes ryal-, byal-, and gyal-. With “we” subjects, speakers generally use the special “we” venitive prefixes ryop-, byop-, and gyop-. (Some speakers may use the ordinary venitive prefixes with “we” subjects, but we will not do so in this book.)

|

Riedtyuga ra gyia., Ryaltyuga ra gyia. |

“I come and cut flowers.” |

|

Ryoptyugën ra gyia. |

“We come and cut flowers.” |

|

Biedgyaa., Byalgyaa. |

“I came and danced.” |

|

Byopgyaën. |

“We came and danced.” |

Just as with andative verbs, some speakers use a different base for some venitive verbs with a “we” subject. Sometimes these special “we” forms look more like the regular non-venitive than like the venitive:

|

Ryopdacwën cotony., Ryoptacwën cotony. |

“We come and put on a shirt.” (venitive riedtacw) |

|

Ryopdilyën. |

“We come and fight.” (venitive riedtily) |

Special venitive “we” forms are listed in the verb charts at the end of this book. (Or will be at some point…)

Tarea Tap xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

Part Teiby. Change each of the sentences below so that it is a venitive (“comes–and”) sentence. Translate both your original and new sentences into English.

a. Rbeluzh betsa lua.

b. Bculo Lia Sily bdo.

c. Ycwa mes cwen e?

d. Cabuzhën ra mniny. (warning: this one is sneaky in several ways!)

e. Byual becw.

f. Btyuri fruat.

g. Ytyugën gyag.

h. Rcwany zhyet mniny.

Part Tyop. Now, make up four new venitive sentences with the following bound pronoun subjects. Try to use different verbs from the ones in Part Teiby. Then, work with a partner and read your new sentences to each other. Make sure you can understand what the other person is saying!

a. “I”

b. “you all”

c. “we”

d. “he (prox.)”

Irregular venitive verbs. All verbs use the same base in the venitive as in the andative. Verbs that have irregular andatives have irregular venitive forms as well — they use the same base with the venitive prefixes that they use with andative ones, but this is different from the regular habitual base. (The verb charts at the end of the book list irregular venitive (“ven.”) verbs, and these irregular venitives also appear in the Rata Ra Dizh.) This section includes a review of the irregular bases that you learned for andative verbs in Lecsyony Tseinyabtyop.

For some verbs, the venitive base is the same as the irrealis stem:

| ria “drinks” | gyia “will drink” | riedgyia “comes and drinks” |

| rgyet “plays” | cyet “will play” | riedcyet “comes and plays” |

For d-base verbs whose perfective base starts with d, the venitive base starts with t:

| rau “eats” | bdau “ate” | riedtau “comes and eats” |

| rany “sits down on” | bdany “sat down on” | riedtany “comes and sits down on” |

Many other base-changing verbs with perfective bases starting with d work the same way:

| rgue “cusses” | bde “cussed” | riedte “comes and cusses” |

| rgap “slaps” | bdap “slapped” | riedtap “comes and slaps” |

| rguieb “sews” | bdieb “sewed” | riedtieb “comes and sews” |

Similarly, raisy has a perfective that starts with t, and its venitive base starts with t as well:

| raisy “sleeps” | btaisy “slept” | riedtaisy “comes and sleeps” |

On the other hand, other base-changing verbs and some verbs whose bases start with d have venitive bases starting with nd or ld (both are correct). Usually, these are verbs whose progressive forms also include nd / ld.

| rbez “waits for; sits (form.)” | riedndez/riedldez “comes and waits for; comes and sits (form.) |

| rdats “spies on” | riedndats/riedldats “comes and spies on” |

| rbe “chooses” | riednde/riedlde “comes and chooses” |

| rgu “puts down” | riedndu/riedldu “comes and puts down” |

| rdiby “ties onto” | riedndiby/riedldiby “comes and ties onto” |

You don’t see many words in Zapotec that have three consonants in a row, like dnd or dld! These are pronounced with the first syllable ending in d and the next starting with nd or ld. (You might even feel you hear a ë vowel after the d of the venitive prefix as <riedëndez> or <riedëldez>.)

Usually the vowel pattern of an venitive verb is the same as that of the verb it is formed from, but not always:

| racw “puts on (a shirt)” [ra’ahcw] | bdacw “put on (a shirt)” [bda’ahcw] | riedtacw “comes and puts on (a shirt)” [rìe’dtaa’cw] |

| reipy “tells” [re’ihpy] | gueipy “will tell” [gue’ipy] | riedgueipy “comes and tells” [rìe’dgue’ihpy] |

And some venitive verbs (and their andative counterparts) are just plain irregular!

| ruxna “gets married” [ru’x:nnaàa’] | riedguexna [rìe’dgue’x:nnaàa’] “comes and gets married”, riguexna [rigue’x:nnaàa’] “goes and gets married” |

| rreizh “calls” [rree’ihzh] | riedteizh [rìe’dtee’ihzh] “comes and calls”, riteizh [ritee’ihzh] “goes and calls” |

In other ways, venitive verbs with irregular bases work just like venitive verbs with regular bases. They also use the prefixes gyied- and bied- and the special “we” subject prefixes ryop-, gyop-, and byop-, and they may use the special “I” subject prefixes ryal-, gyal-, and byal-. Remember that the venitive base is always the same as the andative base.

Tarea Gai xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

Part Teiby. Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. Tomas came and put on a shirt.

b. They will come and get married.

c. Don’t come and spy on me!

d. The tailor came and sewed the skirt.

e. The child came and played with him.

f. We will come and dance.

Part Tyop. The sentences in Part Teiby are all venitive sentences. Change each of the sentences above so that it is not a venitive sentence, as in the example. Translate your new sentences into English.

Example. Ryoptyugën ra gyia. “We come and cut flowers.”

Answer. Rtyugën ra gyia. “We cut flowers.”

Fot Tyop xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby. Riguexnarëng Bac. Some brides have two wedding dresses, a city-style white one like this, and a traditional Zapotec one.

Fot Tyop xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby. Riguexnarëng Bac. Some brides have two wedding dresses, a city-style white one like this, and a traditional Zapotec one.

§21.4. Locations around the house

Compare the following two sentences:

|

Lanyu ri duzh muly. |

“There is some money in the house.” |

|

Liaza ri duzh muly. |

“There is some money in my house.” |

Both of these sentences work a bit differently from what you learned about locational phrases in Lecsyony Tseinyabchon and Lecsyony Galy.

The first sentence begins with the word lanyu [làa’nyu’uh] “in the house”. This is a compound of lany plus yu, pronounced as one word. There are several of these compound preposition-plus-“house” words:

|

lanyu [làa’nyu’uh] “in the house” guecyu [gue’ehcyu’uh] “on the top of the house”, “on the roof of the house” detsyu [dehtsyu’uh] “behind the house” cweyu [cwe’yu’uh] “beside the house” ruyu “in front of the house” , “in the doorway of the house” |

In addition, guecyu means “roof” and ruyu means “doorway”.

Some speakers also use loyu [lohyu’uh] as well as ruyu to mean “in front of the house”. For these speakers, ruyu means in the area right in front of the door, and loyu means in the area in front of the house, but not directly in front of the door, and very likely farther away.

Fot Chon xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby. A room in a house in San Lucas.

Fot Chon xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby. A room in a house in San Lucas.

Here are some more examples of how to use these words:

|

Zugwaa guecyu. |

“I’m standing on the house.” |

|

Bzuat ra mniny detsyu. |

“The boys played behind the house.” |

|

Lanyu cabezrëb. |

“They (resp.) are sitting in the house.” |

(The last sentence contains an example of the formal use of rbez. When it means “sits”, “lives”, or “is at home”, this verb can only be used with a subject who you’d address with formal “you” – perhaps the people in the house in the last example are teachers, priests, or your grandparents!)

The second sentence, Liaz rapa duzh muly, is unexpected because it does not include a preposition. Like the “large locations” you learned about in Lecsyony Galy, the possessed form of “house”, liaz, does not need a preposition to express “in”.

Other prepositions can’t be used directly with liaz either. If you want to express other locations with liaz, you need to use one of the new compound “house” prepositions before liaz, as in

|

Zugwaa guecyu liaza. |

“I’m standing on my house.” |

|

Bzuat ra mniny detsyu liaz mes. |

“The boys played behind the teacher’s house.” |

|

Zu zhyap ruyu liaz xnanmamni. |

“The girl is standing in the doorway of her grandmother’s house.” |

In phrases like guecyu liaza, detsyu liaz mes, and ruyu liaz xnanmamni, the compound “house” preposition comes first, followed by liaz and the possessor.

Tarea Xop xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

Create new Zapotec sentence that include the locations below. Use different verbs! Then translate your Zapotec sentences into English.

a. in front of my house

b. behind the house

c. beside the house

d. on top of the doctor’s house

e. in her house

f. behind his house

g. in front of the house

h. beside your house

i. in the house

j. on the roof of the house

§21.5. The incompletive

Ria “goes”, ried “comes”, andative verbs, and venitive verbs do not have regular progressive forms beginning with ca-. However, there is another form of these verbs beginning with a z- prefix, the INCOMPLETIVE (abbreviated as “inc.”) which can be used to express a progressive meaning. Here are some examples:

|

Zaa scwel chi mnaa loëng. |

“I was going to school when I saw him.” |

|

Zyoën Bac. |

“We are going (are on our way) to Tlacolula.” |

|

Ziedu liaza e? |

“Were you coming to my house?” |

|

Zetauwi guet. |

“He was going to eat.” |

|

Zyopgwiën cuanu. |

“We were coming to visit you.” |

(The last example uses the complex verb riedgwi cuan. Note that the object of “comes and visits” (in the translation here, “comes to visit” probably sounds better to you in English) is a bound pronoun following cuan.)

The incompletive is a verb form like the ones you’ve already learned — habitual, perfective, progressive, and irrealis — but it is different from these because it’s only used with a few verbs. Most Zapotec verb forms can be made from any verb (although, as you know, some verbs are not used in certain forms — for example, some verbs that have habitual forms do not have progressive forms). Only three verbs, however, have incompletive forms.

The incompletive can express the idea of ongoing motion, an idea which often comes out more clearly in the past, so it often is used to express a progressive meaning. With ria “goes”, a good translation of the incompletive is often “is on the way to” (or “is on his way to”, “is on her way to”, “am on my way to”, etc.).

Progressive forms of motion verbs in English usually are used to refer not to ongoing motion, but to the future. (I am going to sing usually doesn’t mean I am on my way to sing, but rather I will sing, right?) Thus, the fourth sentence above means “He was on his way to eat”, not “He was planning to eat”. When you want to refer to the future, you should use an irrealis form, not an incompletive.

The “goes” and “comes” incompletives are ze [zèe] “was going” and zied [ziìe’d] “was coming”. As these examples show, we will use past progressive translations here for these incompletive forms, but present (and other) translations are often also possible. The pronunciation of some incompletive forms is irregular. Here are the incompletive forms used with bound pronouns starting with vowels:

|

zaa [za’-a’] “I was going” zeu [ze’-ùu’] “you were going” zeëng [zeèe’-ëng] “he (prox.) was going” zei [ze’èi’] “he (dist.) was going” zeëb [zee-ëhb] “he (resp.) was going” zeëm [ze’-ëhmm] “he (an.) was going” zeazh [zee-ahzh:] “he (fam.) was going” zoën [zoo’-ëhnn] “we were going” zead [zee-ahd] “you guys were going”

zyala [zyàa’lla’] “I was coming” ziedu [zi’ìe’dùu’] “you were coming” ziedëng [zi’ìe’dëng] “he (prox.) was coming” ziedi [zi’ìe’dih] “he (dist.) was coming” ziedëb [zi’ìe’dëhb] “he (resp.) was coming” ziedëm [zi’ìe’dëhmm] “he (an.) was coming” ziedazh [zi’ìe’dahzh:] “he (fam.) was coming” zyopën [zyoo’pëhnn] “we were coming” ziedad [zi’ìe’dahd] “you guys were coming” |

The incompletive andative prefix is ze- [zee] “was going to”, and the incompletive venitive prefix is zied- [zi’ìe’d] “was coming to”. These prefixes are used with the normal andative and venitive bases that you already know, as in

|

zetau “was going to eat” ziedtau “was coming to eat”

zegya “was going to dance” ziedgya “was coming to dance”

zeguexna “was going to get married” ziedguexna “was coming to get married” |

With a “we” subject, the incompletive andative prefix is zo- [zoo’] and the incompletive venitive prefix is zyop- [zyoo’p], as in

|

zodauwën “we were going to eat” zyopdauwën “we were coming to eat”

zoguexnaën “we were going to get married” zyopguexnaën “we were coming to get married” |

(As you learned in Lecsyony Galy, a different base is often used for andative and ventive expressions with a “we” subject.)

Once again, it’s important to remember that an incompletive Zapotec sentence with a translation like “We were going to get married” does not mean “We were planning to get married” or “We were supposed to get married”, but rather more like “We were on our way to get married”. The incompletive always expresses actual motion (not just a future meaning — for those, you should use the irrealis or another verb form you will learn about in Lecsyony Galyabtyop, the definite).

The incompletive can be used in a number of different ways, which you’ll learn more about as you study more Zapotec. The most common meaning is the one already presented, progressive motion. Progressive motion is incomplete because the motion is in progress; the goal has not been reached.

Another idea that is often expressed with the incompletive is one-way motion. Compare the use of the incompletive and the perfective in the following sentences:

|

Zeëng Meijy. |

“He went to Mexico City (and he’s still there).” |

|

Gweëng Meijy. |

“He went to Mexico City (and he’s back).” |

In the first example (with the incompletive), the motion (or the trip) is incomplete: the subject has not returned. In the second (with the perfective), the trip has been completed, so the motion is not incomplete.

In telling stories, Zapotec speakers often use the incompletive to refer to ideas we’d express with a past verb in English. Here are some examples:

|

Chi bragueli zeëng Nort. |

“When the next day came he went to the United States.”, “The next day he went to the United States.” |

|

Niebagli zyopën Nort. |

“That’s why we came to the United States.” |

|

Cuan laëng zyala. |

“I came with him.” |

One way to think of how this works is that the incompletive is used because at the time the speaker relates this part of the story, the story is not yet complete.

Listen to Zapotec speakers, and you’ll learn more ways to use the incompletive.

Tarea Gaz xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

Part Teiby. Read each of the Zapotec sentences below out loud, then translate them into English.

a. Zaa liaza.

b. Ziedad lo gyia e?

c. Los Angl ziedi chi zaa Ndua.

d. Zeu ydo e?

e. Cali zeazh?

f. Tu zied?

g. Cali ziedu?

h. Lo nya zeëm.

i. Zerëng scwel.

j. Zyopën Bac.

Part Tyop. Practice using incompletive andative and venitive forms by translating the following into Zapotec. Then read your Zapotec sentences out loud.

a. I was going to ask permission from my father.

b. Was he coming to steal the money?

c. We were going to feed the dogs.

d. She was coming to wake up the baby.

e. Were you going to kill the turkey?

f. I was coming to give this book to her.

g. We were note coming to fight with you all.

h. Were you all going to listen to Juana?

i. They were coming to pay the cook.

j. The teacher was going to put the bag down.

§21.6. More about numbers

Number phrases. As you know, you can form a noun phrase with a number plus a noun:

|

tyop buny |

“two people” |

|

gaz liebr |

“seven books” |

You can also form a phrase with a number plus a bound pronoun:

|

tyopën |

“two of us” |

|

gazrëb |

“seven of them“ |

These number phrases are used in sentences like the following, either as subjects or as objects or objects of prepositions:

|

Tyopën choën. |

“Two of us are going.” |

|

Gazrëb bgyarëb. |

“Seven of them danced.” |

|

Xonad bseidyad lai. |

“Eight of you guys taught him.” |

|

Bseidy mes tsërëng. |

“The teacher taught ten of them.” |

|

Bdilya tapad. |

“I found four of you guys.” |

|

Mnayu lo chonri e? |

“Did you (form.) see three of them?” |

Look again at the first two sentences. They’re unusual in two ways. First, it is very common for subject number phrases to come at the beginning of the sentence. This is so common that such sentences don’t really have the emphasis we’d expect from focus (so we don’t translate these subjects as focused). Second, and more importantly, when you have a number phrase subject that includes a bound pronoun, the verb must still have the corresponding bound pronoun subject. Here’s the pattern:

| number | -bound pronoun | verb | -bound pronoun | rest of sentence |

| Tyop | -ën | cho | -ën. | |

| Gaz | -rëb | bgya | -rëb. | |

| Xon | -ad | bseidy | -ad | lai. |

Tarea Xon xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. Two of them went and asked permission from the teacher.

b. Three of us were coming to feed the teachers.

c. Ten of you guys came and woke up the babies.

d. Were you coming to kill two of them (an.)?

e. We came and gave five of them to the teacher.

f. The men put three of them down behind my house.

g. Two of them will go and get married.

h. My mother went and sewed four of them.

i. The girl was going to play with six of them.

j. Ten of them will come and dance.

“The” with number phrases. What’s the difference between Two men left and The two men left? In the second, you’re talking about a particular set of two men: you could also say Both men left. Here are some Valley Zapotec sentences with “the” numbers:

|

Yropta buny bria. |

“The two men left.”, “Both men left.” |

|

Ygyontën nacën mes. |

“The three of us are teachers.” |

|

Ydapta blidguidy bgutya. |

“I saw the four mosquitos.” |

|

Ydaptarëng bgutya. |

“I killed the four of them.” |

These sentences use the following new number words:

|

yropta [yro’pta’] / ropta [ro’pta’] the two of, both of ygyonta [ygyòonnta’] / gyonta [gyòonnta’] the three of ydapta [yda’pta’] the four of |

These special words are used with following nouns or bound pronouns. As the second example above shows, if a “the” number phrase is the subject of a sentence, the verb still needs a bound pronoun subject. Before bound pronouns beginning with vowels, the a of the –ta ending drops, as in yropti “both of them (dist.)”. Before the distal plural ending –ri, this final a may become i: yroptiri / yroptari “both of them (pl. dist.)”. (Occasionally, speakers don’t use the –ta ending on these new words.)

Numbers aren’t used alone. Look at the following question and four possible answers to it:

|

—Bal blidguidy bgutyu? |

“How many mosquitos did you kill?” |

|

|

—Tapi bgutya. |

“I killed four of them.” |

|

| OR |

—Tapri bgutya. |

“I killed for of them.” |

| OR |

—Tapi. |

“Four of them.” |

| OR |

—Tapri. |

“Four of them.” |

In English, we might answer the question by saying simply Four or I killed four, but you can’t do this in Zapotec. When you use a number (either a regular number or one of the new “the” numbers) in a sentence, you must include the noun or pronoun that the number refers to in order to make a complete response. (These, and also the more complete tap blidguidy “four mosquitos”, are not complete sentences, of course.)

Something else is unusual about the answers Tapi bgutya and Tapi. Although we’re talking about “mosquitos” in the plural, the pronoun is singular. When they’ve mentioned a number, Zapotec speakers don’t think it’s necessary to use a plural “they” pronoun. In cases like this, either the singular or the plural pronoun is ok. In general, when you are referring to people, you’ll use plural pronouns, but when you are referring to animals (especially smaller ones) or to inanimate objects, it’s ok to use singular ones. Listen to speakers and see what they do!

It’s fine to use number words by themselves when you’re just counting things (saying teiby — tyop — chon — tap — gai …), of course.

Tarea Ga xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

Create new sentences in Zapotec that use the following phrases.

a. both of us

b. the three of you

c. the four priests

d. six of you

e. ten of them

f. the three bulls

g. the two of you (form.)

h. four of you

i. the two women

j. seven of us

§21.7. Reverential pronouns

There’s just one more Zapotec pronoun you need to learn! Look at the following sentences, which contain REVERENTIAL pronouns:

|

Gacne Dyoz danoën. Gacneiny danoën. |

“God will help us. He will help us.” |

|

Nden ydo xten Dad Bied San Luc. Nden ydo xteniny. |

“This is the church of Holy St. Luke. This is his church.” |

|

Cayunyri alabar Dyoz. Cayunyri alabar lainy. |

“They were praising God. They were praising him.” |

|

Angle cayuny alabar Dyoz. Cayunyriny alabar Dyoz. |

“The angels were praising God. They were praising God.” |

Reverential (rev.) pronouns are used to refer to God, the saints, and other holy individuals. The bound singular reverential pronoun is –iny [ihny], and the free singular reverential pronoun is lainy [làa’-ihny]. The plural pronouns are bound –riny [rihny] and free lariny [làa’rihny]. Like the other Valley Zapotec pronouns you have learned, reverential pronouns are gender neutral.

Because the singular bound pronoun starts with a vowel, it is normally attached to vowel final stems in a separate syllable, just as with other bound pronouns that begin with vowels. Reverential forms of the verbs you already know are given in the Verb Charts at the end of this book.

Reverential pronouns aren’t only used to refer to holy people, however. Traditional Zapotec speakers also use them to refer to the important items needed to sustain life — water, tortillas, the sun, and the moon. Here are some examples:

|

Yzhi nyis. Yzhiiny. |

“The water is going to spill. It’s going to spill.” |

|

Bdau becw guet. Bdau becw lainy. |

“The dog ate the tortilla. The dog ate it.” |

|

Rdyeny wbizh rata zhi. Rdyenyiny rata zhi. |

“The sun rises every day. It rises every day.” |

|

Mnaa lo beu. Mnaa loiny. |

“I saw the moon. I saw it.” |

These examples show that if a traditional speaker wants to refer to one of these items with a pronoun, that pronoun should be a reverential pronoun, whether the item is a subject, object, or prepositional object. Very traditional speakers may use reverential pronouns even to refer to any liquid (not just water) or to any baked goods (not just tortillas). On the other hand, more modern speakers (especially those in the United States) often use ordinary proximate or distal pronouns to refer to all these items.

Listen, and you may hear that some speakers use reverential pronouns to refer to other items as well. You’ll learn about one additional use of reverential pronouns in Lecsyony Galyabtyop, and another in S-25 (on time expressions). In addition, there is another form of the reverential pronoun that you may hear speakers use on occasion, an ending –ni [ni’]. The –ni ending is not as common as the –iny ending, so we won’t practice it here, but you’ll hear it used in some expressions.

Tarea Tsë xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby.

First create new Zapotec sentences that talk about the following items. In some sentences, the holy items should be subjects, in others objects, in others possessors, in others prepositional objects. Then change each sentence so that it uses a reverential pronoun instead of the noun, as in the example. Translate the new sentences.

Example. the angels

Answer. Mnoo lo ra angle e? “Did you see the angels?”

Mnoo loriny e? “Did you see them?”

a. God

b. the moon

c. the angel

d. the sun

e. water

f. the three tortillas

g. St. Anne

h. the tortilla

i. beer (assume you’re a very traditional speaker)

j. St. Luke

Fot Tap xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby. Houses in San Lucas, seen from the roof of the church.

Fot Tap xte Lecsyony Galyabteiby. Houses in San Lucas, seen from the roof of the church.

Abbreviations

inc. incompletive

rev. reverential

ven. venitive

Prefixes

z- [z] (inc. prefix)

ze- [ze] (inc. and. prefix)

zied- [zìe’d] (inc. ven. prefix)

zo- [zoo’] (inc. ven. prefix for verbs with a “we” subj.)

zyop- [zyoo’p] (inc. and. prefix for verbs with a “we” subj.)

Endings

-iny [ihny] / –ni [ni’] he, she, it (rev. sg. bound pronoun)

-ni [ni’] see –iny

-riny [rihny] they (rev. pl. bound pronoun)

Comparative note. As you know, there is a lot of grammatical variation among the Valley Zapotec languages in pronoun usage. All Valley Zapotec languages that we know of have reverential pronouns, but other speakers may use them differently from the way they are described in this lesson. If you know speakers of other varieties of Valley Zapotec, you will learn other pronoun systems.

A type of VERB that means "comes and ...".

A form of certain motion VERBS that expresses incomplete motion and may have a number of different English translations, depending on the CONTEXT in which it is used; abbreviated as "inc.". Out of a particular context, the incompletive usually expresses a past PROGRESSIVE meaning.

A PRONOUN used to refer to God, the saints, and other holy individuals, as well as important items needed to sustain life — water, tortillas, the sun, and the moon; abbreviated as "rev.".