20. Lecsyony Galy: Runya zeiny xpart xtada “I am working in place of my father”

This lesson explains more about using native prepositions. Section §20.1 introduces more native prepositions. Sections §20.2 and §20.3 tell how to use native prepositions with people and animals as objects. Section §20.4 presents words for putting things in locations, and section §20.5 special location words with lo. Sections §20.6 and §20.7 are more about expressing location and questioning objects of native prepositions. Section §20.8 tells how to use modifying phrases with native prepositions.

Ra Dizh

cam [ca’mm] bed (modern style)

dyen [dye’nn] store

don [do’onn] so (indicates a conclusion the speaker has drawn)

du [dùùu’] rope

fruat [frua’t] fruit

gagyeita [gagye’ita’] / gagyei [gagye’i] around

gayata [gayàa’ta’] / gaya [gayààa’] along (a river, for example)

lad [làad] between (non-living things)

lai [lài’] 1. in the middle of, in the midst of; 2. between (living things)

lo bcu [loh bcùùu’] altar (in a church)

lo gueizh [loh guee’ihzh] pueblo, town, village § e-poss. lazh [la’ahzh:]

lo gyia [loh gyìi’ah] market

lo pyeiny [loh pyeeiny] altar (in a home)

Los Angl [Lohs A’nngl] Los Angeles

losna [losnnaàa’] in the hand of, in the hands of (prep.)

luan [lùàa’n] sleeping platform (traditional style of bed)

na [nnaàa’] 1. branch (of a tree) (e-poss.); 2. on the branch of (prep.)

nez [ne’ehz] 1. road, way; 2. (used before a locational phrase, sometimes indicating “roughly”)

ni na [nih nàa] in (a town or city)

puan [pu’ann] at the peak of, on the (very) top of (prep.)

rguixga [rgui’xga’ah] lays (something) down (in a location)

rsan losna [rsàa’an losnnaàa’] leaves (property) to (someone) > rsan, losna

ryan [ryàa’an]stays in, stays at (a place)

ryengw [rye’enngw] gringo (Anglo, white person from the United States or possibly Europe)

rzeiby [rzèèi’by] hangs (something) (in a location)

rzu [rzuh] stands, stands up (something) (in a location)

rzub [rzùu’b] places (something) (in a location); sets (something) down (in a location)

rzubga [rzubga’ah] / [rzùu’bga’ah] / [rzùubga’ah] sets (something) (in a location)

rzugwa [rzugwa’ah] stands, stands up (something) (in a location)

rzundi [rzundii] stands erect (in a location) § irr. sundi; neut. zundi

rzundi [rzundii] stands (something) erect (in a location)

Santa Mony [Sánntah Moony] Santa Monica

Stados Unied [Stadohs Uniied] the United States

Tijwan [Tijwa’nn] Tijuana

totad [to’taad] assistant mayordomo (diputado)

unibersida [unibersidaa] university; college

West Los Angl [We’st Lohs A’nngl] West Los Angeles

xpart [x:pa’rt] in place of, on behalf of, instead of

Xiëru Zalo Ra Dizh

Rzundi “stands erect (in a location)” is another standing verb which is used similarly to rzu and rzugwa, which you learned in Lecsyony Tseinyabchon.

§20.1. More native prepositions

Although most native prepositions are not borrowed, this is not always true. Here’s a sentence containing a new native preposition, puan:

|

Puan gyag zubga many. |

“The bird is sitting at the top of the tree.” |

Puan [pu’ann] “on the peak of, at the top of” is a word that is borrowed from Spanish, but it is considered a native preposition. Like other native prepositions but unlike Spanish ones, puan is used with bound pronoun objects rather than free ones, as the second example shows. Puan is usually used to tell about locations at the top of something with a relatively pointed top, such as a tree or mountain.

A few additional native prepositions are not related to body parts. Two examples are lai [lài’] “in the middle of, in the midst of; between (living things)” and lad [làad] “between (non-living things)”.

|

Lai ra buny zugwaën. |

“We are standing in the middle of the people.” |

|

Lad ra yu bzhuny mniny. |

“The boy ran between the houses.” |

|

Lai Bed cuan Chyecw zu Lia Len. |

“Elena is standing between Pedro and Chico.” |

Two other new native prepositions, gagyeita [gagye’ita’] / gagyei [gagye’i] “around” and gayata [gayàa’ta’] / gaya [gayààa’] “along (a river, for example)”, each have two forms, with and without –ta. Speakers use these both with and without the –ta, but the form with –ta seems to be more common, so that’s probably the best one to learn.

|

Gagyeita zhyet bzhuny ra becw. |

“The dogs ran around the cat.” |

|

Gayata gueu bzaën. |

“We walked along the river.” |

Like all other native prepositions, these native prepositions take bound pronoun objects:

|

Puani zubga many. |

“The bird is sitting at the top of it.” |

|

Laiyën zugwa ra buny. |

“The people are standing in the middle of us (in our midst).” |

|

Ladri bza mniny. |

“The boy walked between them.” |

|

Gagyeitëng bzhuny ra becw. |

“The dogs ran around him.” |

Puan, lai, and lad work like possessed nouns when bound pronoun endings are added. However, the a of the –ta ending on gagyeita and gayata usually drops when you add a bound pronoun, as in gagyeitëng.

A final new native preposition is xpart [x:pa’rt] “in place of, on behalf of, instead of”. You saw an example of this in Gal Rgwe Dizh Gai, when Megan asked Jwanydyau,

|

Don totad nacu xpart xtadu? |

“So you are an assistant mayordomo in place of your father?” |

Like puan, xpart is based on a Spanish borrowing, but it includes the possessive prefix x– and is considered a native preposition because it takes bound pronoun objects, as in

|

Runya zeiny xpartëng. |

“I’m working in his place.” |

Xpart is only used with human objects.

Part Teiby. How many parts of the man’s and woman’s bodies in Fot Teiby (on the next page) can you label with their Zapotec names?

Part Tyop. Work with a classmate to make sure that you know all the body part words and native prepositions from Lecsyony Tsëda and Tseinyabchon. Make up a sentence for each word, and see if your classmate can understand it.

Part Chon. Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. We built houses along the river.

b. Do you see the deer in the middle of the trees?

c. Those cats are chasing the chicken around the chair.

d. Can you work instead of me?

e. The birds are on the very top of the tree.

f. The ribbon is around it.

g. Leon dried the dishes on his sister’s behalf.

h. My cat is on the very top of it.

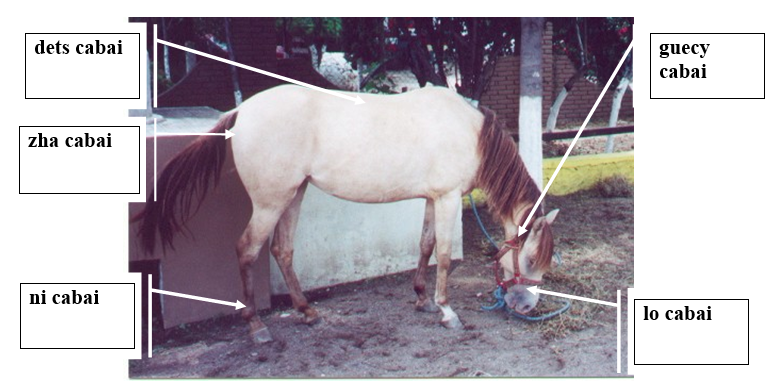

Fot Teiby xte Lecsyony Galy. Mna cuan nguiu.

§20.2. Using Native Prepositions with People as Prepositional Objects

To begin this section, you should review the words for the parts of the body, especially those that are also used as native prepositions, in Lecsyony Tsëda and Lecsyony Tseinyabchon. Do you know the two meanings of gueicy, lo, lany, ni, ru, dets, and zha (or zhan)? What about cwe, which is a preposition, but is used to name a body part only by certain speakers? Some other words for body parts are usually not used as prepositions but are worth reviewing as well, including na, dyag, zhacw, and teix. Completing Part Teiby of Tarea Teiby will help you review these words.

Zapotec speakers use some native prepositions differently than you might expect when the object of the preposition is a person or an animal. When you talk about something being located on or near a person’s body, you don’t use native prepositions which look like body part terms the same way you do to specify locations relative to physical objects (as in Lecsyony Tseinyabchon).

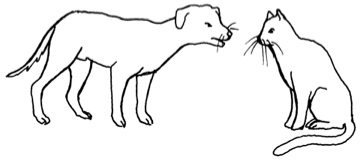

For example, look at Fot Tyop below. Cuan becw? Where is the dog standing? The dog is on the boy’s head. So the best way to describe this scene is to say Becw zu guecy mniny.

Fot Tyop xte Lecsyony Galy. Becw zu guecy mniny.

You might think that you could use lo, the normal word for “on”, in this sentence. But since lo comes from the word meaning “face”, it isn’t appropriate to use here (since the dog is not on the boy’s face!). Instead, we use guecy, which can have the meaning “on the head of” when it’s used to locate an item with respect to a person’s body.

A good way to understand how this works is to imagine a line from the item you’re telling the location of (the subject of the locational sentence) to the person or animal you’re using as a REFERENCE (the item you are using to help specify the location of the subject; that is, the prepositional object). The part of the reference’s body that this line touches is the preposition to use. Thus, in Fot Tyop, the line from the dog to the boy goes to the boy’s head, so guecy is the right preposition.

Now, look at Fot Chon, and think about how you might describe the location of the man relative to the woman (with the woman as a reference).

Fot Chon xte Lecsyony Galy. Tyop buny Dizhsa.

In English, we could say The man is sitting beside the woman, so you might think it would be best to use cwe here. But remember that imaginary line! A line from the man to the woman won’t go toward her side, but rather toward her front or, as we’d think of it in Zapotec, her face. So what you should say here is Nguiu zub lo mna. As you know, one of the meanings of lo is “in front of”, and that is the right preposition here, even if it might not be your first choice in English. In Zapotec, cwe is used to say that one thing is “beside” another only if the first one is at the side of the second. (This works the same way even for speakers who don’t use cwe as a body part word.)

Tarea Tyop xte Lecsyony Galy.

Look at the pictures below and answer the questions that follow them, using the people in the pictures as references to help specify the locations.

Fot Tap xte Lecsyony Galy

a. Cuan gues?

Fot Gai xte Lecsyony Galy

b. Cuan nguiu?

c. Cuan mna?

Using Fot Teiby (in Tarea Teiby), answer these questions:

d. Cuan mna?

e. Cuan nguiu?

Another preposition related to a body part. Losna [losnnaàa’] means “in the hand of” (or, more explicitly, “on the palm of the hand of”) or “in the hands of”. Usually, this preposition (which contains na “hand” and works like na with bound pronouns) refers to location right on the palm of someone’s hand (as in Fot Xop).

Losna can also be used to refer to inheritance, with the verb rsan losna “leaves (property) to (someone)”, as in

|

Lo nya re bsan xtadmama losnaa. |

“My grandfather left this field to me.”, “My grandfather left this land in my hands.” |

Na as a preposition. Na “hand” can also be used to mean “on the branch of” a tree, as in

|

Many zub na gyag. |

“The bird is sitting on the branch of the tree.” |

Fot Xop xte Lecsyony Galy. Fruat beb losna mna.

§20.3. Using Native Prepositions with Animals as Prepositional Objects

Animal prepositional objects also work differently from inanimate prepositional objects. Fot Xop is a picture of a horse with some important parts labeled.

Fot Gaz xte Lecsyony Galy. Cabai.

Make sure you know all these body parts. Most animal body parts are used very similarly to human body parts for expressing location. There’s a big difference, however, in the use of dets “back” and zha (or, for some speakers, zhan) “buttocks, rear end”, for animals rather than people, as you’ll see.

Fot Xon xte Lecsyony Galy. Mniny cuan ra guan.

Compare Fot Xon (just above) and Fot Gai in Tarea Tyop. Although the angles from which the photographs are taken are different, the relationship of the man to the woman in Fot Gai and that of the boy to the bull in Fot Xon are very similar: in both cases, the subject is standing behind the prepositional object. However, we can’t talk about them the same way in Zapotec. Here are some little dialogues:

Fot Tap:

— Cuan nguiu?

— Nguiu zu dets mna.

Fot Gaz:

— Cuan mniny?

— Mniny zu zha guan.

Once again, the best way to understand this difference is to use the imaginary line technique. The line from the boy (the subject) to the bull (the reference or prepositional object) goes to the bull’s buttocks (zha), not to the bull’s back (dets)! You can’t use dets to talk about the relationship of the boy and the bull in Fot Gaz. (What would it mean to say Mniny zu dets guan?)

You shouldn’t use zha to talk about the relationship of the man and the woman in Fot Tap. When something is behind (or “in back of”) a human, it’s best to use dets. Dets usually expresses “behind” (or “in back of”) a human standing or sitting erect, while zha usually expresses “behind” (or “at the buttocks of”) a four-legged animal. Of course we don’t say “at the buttocks of” in English. What’s important to realize is that Zapotec expresses “behind” and many other prepositional ideas quite differently from English (or Spanish), especially with human or animal prepositional objects.

Next, consider the relationship of the toy woman and deer in Fot Xon. In English, we might say The woman is behind the deer, but you can’t use either dets or zha in Zapotec. Use the imaginary line technique and draw a line from the woman to the deer. The line goes to the deer’s side, so the best answer to the question Cuan mna? is Mna zu cwe bzeiny. Once again, English prepositions and Zapotec prepositions work differently!

Fot Ga xte Lecsyony Galy. Mna cuan bzeiny.

Listen carefully as you hear Zapotec speakers use prepositions with humans and animals as references and you will learn lots more about their use. The imaginary line technique will normally help you figure out what to say.

Tarea Chon xte Lecsyony Galy.

Answer the questions about the pictures below in Zapotec. If an item is given in parentheses, use it as a reference, as in the example. Pay attention to the invisible lines! Finally, translate your answers into English.

Fot Tsë xte Lecsyony Galy.

Example. Cuan bdo? (zhyet)

Answer. Bdo zu zha zhyet. “The baby is standing behind the cat.”

a. Cuan mes? (zhyet)

b. Cuan gyizhily? (zhyet)

c. Cuan mniny? (zhyet)

d. Cuan zhyet? (bdo)

e. Cuan zhyet? (gyizhily)

f. Cuan zhyet? (mes)

g. Cuan becw? (zhyet)

h. Cuan zhyet? (becw)

Fot Tsëbteby xte Lecsyony Galy. Teiby buny Dizhsa cuan tap ryengw. Roger, Brook, Roberto (Bet), Panfila (Lia Pam), and Allen at a guelaguetza in Los Angeles

i. Tu zu cwe Bet?

j. Tu zu cwe Roger?

k. Tu zu lai Lia Brook cuan Lia Pam?

§20.4. Putting things in locations

Many of the locational verbs that you learned in Lecsyony Tseinyabchon are related to verbs that refer to putting things (or people or animals) in locations. Here are the new verbs:

|

rzeiby [rzèèi’by] hangs (something) (in a location) rzub [rzùu’b] places (something) (in a location); sets (something) down (in a location) rzubga [rzubga’ah] sets (something) (in a location) rzugwa [rzugwa’ah] stands, stands up (something) (in a location) rzu [rzuh] stands, stands up (something) (in a location) rzundi [rzundii] stands (something) erect (in a location) |

These words are used in sentences that have four parts: a verb, a subject, an object, and a location phrase. Here are some examples of how these verbs are used:

|

Bzeiby du lo gyag! |

“Hang the rope on the tree!” |

|

Rzub Lia Petr gues guecni rata zhi. |

“Petra places the pot on her head every day.” |

|

Yzubgaën ra liebr lany caj. |

“We will set the books in the box.” |

|

Bzub mna bdo lo gyizhily. |

“The woman set the child on the chair.” |

|

Yzugwayu ra tas cwe gues. |

“Stand the glasses beside the pot (form.)!” |

|

Cazuëng bar lany yu. |

“He is standing the stick in the ground.” |

As you can see, each of these words refers to putting something in a location in a particular position or orientation. Each one could also be translated with “puts” (and often, in English, this will sound better), but in Zapotec it’s important to use a verb that specifies the exact position of the object. Here’s the pattern:

| verb | subject | object | location phrase | rest of sentence |

|

Rzub |

Lia Petr |

gues |

guecni |

rata zhi. |

|

Yzubga |

-ën |

ra liebr |

lany caj. |

|

|

Bzub |

mna |

bdo |

lo gyizhily. |

|

|

Yzugwa |

-yu |

ra tas |

cwe gues. |

|

|

Cazu |

-ëng |

bar |

lany yu. |

|

|

Bzeiby |

du |

lo gyag! |

Of course, imperatives like the last example don’t have subjects (though you know the subject is “you”!), and it’s possible to focus the subject, object, or location phrase to change this basic pattern.

The habitual stems of most of the verbs listed above look just like the habitual stems of some of the locational verbs that you learned in Lecsyony Tseinyabchon. But these “puts” verbs are different from the locational verbs in two ways. First, these verbs do not have corresponding neutral forms. Second, the irrealis stems of these new “puts” verbs are different from the irrealis stems of the locational verbs. The irrealis stems of the “puts” verbs use the regular irrealis prefix y– rather than starting with s:

|

seiby “will hang (by itself, by himself, by herself)” |

(locational verb) |

|

yzeiby “will hang (something)” |

(“puts” verb) |

|

|

|

|

sub “will sit” |

(locational verb) |

|

yzub “will set (something)”, “will place (something)” |

(“puts” verb) |

|

|

|

|

subga “will sit” |

(locational verb) |

|

yzubga “will set (something)” |

(“puts” verb) |

|

|

|

|

sugwa “will stand (by itself, by himself, by herself)” |

(locational verb) |

|

yzugwa “will stand (something)” |

(“puts” verb) |

|

su “will stand (by itself, by himself, by herself)” |

(locational verb) |

|

yzu “will stand (something)” |

(“puts” verb) |

Both types of verbs are used with locational phrases. In addition, the new “puts” verbs are all used with objects, while the locational verbs don’t have objects.

Finally, here’s another “puts” verb that is not related to a locational verb:

|

rguixga [rgui’xga’ah] lays (something) down (in a location) |

Unlike the other “puts” verbs, this one has a normal irrealis (yguixga). But it’s used in the same “puts” pattern as the other new verbs.

Locational and “puts” verbs don’t always have andative forms that speakers are comfortable using. You can ask your teacher what he or she thinks about these.

Tarea Tap xte Lecsyony Galy.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa. Pay attention to whether the verbs should be locational verbs or “puts” verbs.

a. The doctor will sit in the church.

b. Juan will hang Elena’s picture next to your picture.

c. Will you set the baby on the chair?

d. Where will my picture hang?

e. Ignacio says he will stand behind me.

f. I will place the blal on the table.

g. Stand (pl.) the poles in the ground.

h. Would you be so good as to sit in the car?

i. Gloria laid the dog on the (modern) bed.

j. The money is in the box.

k. The cat lay down on the (traditional) bed.

l. Please stand next to Señora Petra (form.).

§20.5. Special location words with lo

Some nouns that refer to locations are almost always used with lo. Here are some examples (some of which you already know!):

|

lo bcu [loh bcùùu’] altar (in a church) lo gueizh [loh guee’ihzh] pueblo, town, village § e-poss. lazh [la’ahzh:] lo gyia [loh gyìi’ah] market lo nya [loh nyààa’] field § e-poss. lo zhia [loh zhihah] lo pyeiny [loh pyeeiny] altar (in a home) lo zhia [loh zhihah] field (e-poss. of lo nya) |

Normally, these words are used with the lo in all contexts, and speakers think of them as including lo (they might even choose to write lo as part of the words, rather than separately, as above). Here are some examples:

|

Gwerëng lo gyia. |

“They went to the market.” |

|

Bleëng fot lo nya. |

“He took a picture of the field.” |

|

Choën lo gueizh. |

“We’ll go to the pueblo.” |

|

Bzugwa Bied Lia Zhuan gues lo pyeiny. |

“Señora Juana put the pot on the altar.” |

As you can see, these new words are used with lo when they are objects of verb phrases like rbe fot, when they name directions taken with verbs like ria, and when they are actually in location phrases (as in the last example). (You might think that there would be two lo‘s in this sentence, the preposition and the beginning of the word for “altar”. But you only need one.)

Listen to the way speakers of Valley Zapotec use the words in this section. Sometimes speakers will omit lo with them. One such case might be when the words are plural. There are two ways to say the next sentence:

|

Bleëng fot ra nya., Bleëng fot ra lo nya. |

“He took pictures of the fields.” |

In this case, when lo nya refers to more than one field, and it’s a normal object, many speakers feel it’s ok to omit lo following the plural marker ra.

Fot Tsëbtyop xte Lecsyony Galy. An altar in a home in San Lucas.

Tarea Gai xte Lecsyony Galy.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa.

a. Put the flowers on the altar. (in a church)

b. A picture of my father is on the altar. (in my home)

c. When are they going to the pueblo?

d. The cows are in the field.

e. Soledad likes to take pictures of her father’s fields.

f. We are standing in front of that altar. (in a church)

g. The church is near the market.

h. Has your friend seen your pueblo?

i. Why is your bull in my field?

j. Did you see him at the market?

§20.6. More about expressing location

Expressing locations without prepositions. To say that an event takes place in a town or city, you might expect to use a word meaning “in”, but lany is never used in such cases in Valley Zapotec. Most commonly, speakers use no preposition at all with large locations like these:

|

Santa Mony nu Lia Len. |

“Elena lives in Santa Monica.” |

|

Tyop buny cagwi lo ra budy San Luc. |

“Two people are looking at chickens in San Lucas.” |

|

Bxela muly par ra saa Ndua. |

“I sent money for my relatives in Oaxaca.” |

|

Rtorëng ra gues Monte Albán. |

“They sell pots at Monte Alban.” |

|

Rnalazu blal ni nu San Diegw e? |

“Do you remember the blal that was in San Diego?” |

The same thing happens when you’re talking about going in the direction of a large location or arriving at a large location. With a smaller location, lany or another preposition is correct, as in

|

Byoën lany teiby edifisy. |

“We went into a building.” |

However, with the name of a town or another large location, speakers usually give the location without a preposition:

|

Chi bzenyu Los Angl, a danoën nuën San Luc! |

“When you arrived in Los Angeles, we were in San Lucas!” |

|

Lany autobuas bzenyën Tijwan cuan laëb. |

“I arrived in Tijuana with him on the bus.” |

|

Bzicy myegr naa Meijy. |

“The border patrol sent me back to Mexico.” |

|

Bed cuan naa byoën San Diegw lany autobuas. |

“Pedro and I went to San Diego on the bus.” |

|

Byan xtad doctor Bac. |

“The doctor’s father stayed in Tlacolula.” |

If you listen to Zapotec conversations you’ll notice two additional things. First, sometimes it’s hard to know whether a location counts as “large”. In the examples below, “school”, “restaurant”, and “the Comedor Mary” are used without an “in” or “at” preposition (even though lany might also be appropriate at times, as in the “into a building” sentence above):

|

A rapa teiby amiegw scwel ni la Lia Araceli. |

“I already have a friend at school whose name is Araceli.” |

|

Comedor Mary uas nizh nax ricy. |

“At the Comedor Mary, the chocolate is very delicious there.” |

|

A guc tsë iaz cayuny Chiecw zeiny xte meser rrestauran ni la Yagul. |

“For ten years Chico has been working as a waiter in a restaurant called Yagul.” |

Listen, and see if you can discover when the Zapotec speakers you know feel that a location is “large”! The decision may involve whether the speaker is thinking about an actual building, or not.

(Houses are special in Zapotec, however. You’ll learn more about expressing location of houses and relative to houses in Lecsyony Galyabteiby. For now, don’t try to do this!)

Ni na for “in”. A final point to notice is that sometimes Zapotec speakers use ni na [nih nàa] before large location names. Here are some examples:

|

A guc tsë iaz cayuny Chiecw zeiny xte meser rrestauran ni la Yagul ni na West Los Angl. |

“For ten years Chico has been working as a waiter in the restaurant called Yagul in West Los Angeles.” |

|

Choën ni na Bac. |

“We’re going to Tlacolula.” |

|

Unibersida ni na San Diegw bsedya Dizhsa. |

“I studied Zapotec in college in San Diego.” |

(The last example contains universida with no preposition and ni na before San Diegw!) In the Ra Dizh for this lesson and Blal xte Tiu Pamyël, ni na is translated as “in”, but you can’t use ni na everywhere you can use lany. It may seem as though it’s most common to hear ni na before borrowed names, but since ni na can be used with Bac (as in the second example above), that’s not a regular rule. Once more, the best thing to do is to listen to how speakers use this phrase.

Tarea Xop xte Lecsyony Galy.

Part Teiby. Make up Zapotec sentences that talk about events that take place in the following locations, or about motion toward these places. Then translate your new sentences into English.

a. lo gueizh

b. Califoryën

c. dyen

d. lo gyia

e. Meijy

f. lo nya

g. restauran

h. San Dyegw

i. ydo

j. Bac

k. Ndua

l. San Luc

Part Tyop. Work with another student. Take turns reading your sentences aloud to one another. The student listening should try to write down what he or she hears, then translate the sentence into English and check to see if it’s right!

Telling the location of “large locations”. In Lecsyony Tseinyabtap you learned that the locational verb na is generally not used in expressing locations – normally you use a positional verb. There’s one exception to this rule, though. When the item you want to locate – the subject of your locational sentence – is a “large location”, such as a town or one of the buildings and institutions we’ve discussed here, the usual verb to use is na. (Perhaps the reason for this is that large locations don’t stand or sit or lie!) Here are some examples:

|

Bac na Ndua. |

“Tlacolula is in Oaxaca.” |

|

Scwel na cwe ydo. |

“The school is next to the church.” |

Tarea Gaz xte Lecsyony Galy.

Part Teiby. Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Ingles.

a. Lo gueizh na Ndua.

b. Los Angl na Califoryën.

c. Dyen na dets restauran.

d. Lo gyia na cwe ydo.

e. Ndua na Meijy.

f. Califoryën na Stados Unied.

g. Restauran na cwe scwel.

h. San Luc na Ndua.

Part Tyop. Make up a question based on each of the above statements. For half of the questions, you should ask the question with a different location phrase, as in the first example. For the others, you should make the question negative (see Lecsyony Gaz if you need a review on negative questions!).

Example (a1). Lo gueizh na Califoryën e? (different location phrase)

Example (a2) Queity na lo gueizh Ndua e? (negative question)

Part Chon. Work with a partner and take turns asking each other your new questions. Respond to the questions with a or quiety plus a full sentence, as in the example:

Example (a1) Lo gueizh na Califoryën e? Queity, lo gueizh na Ndua.

Example (a2) Queity na lo gueizh Ndua e? A, lo gueizh na Ndua.

Nez. The word nez [ne’ehz] is often used in locational sentences. This word means “path”, but in locational sentences it often seems to have a meaning like “roughly”. So you might hear

|

Scwel na nez cwe ydo. |

“The school is (roughly) next to the church.” |

from a speaker who wasn’t sure this was the best characterization (if the two buildings were not lined up, for example). Another example is

|

Gyag zu nez cwe scwel. |

“The tree stands (roughly) next to the school.” |

Here, the speaker might be indicating that because the tree and the school were of such different sizes it was awkward to think of them as really “next to” each other.

Sometimes, however, you may hear nez before a location phrase where “roughly” does not make sense as a translation. Although you may find it tricky to use nez, you should listen to how speakers use this word, and you’ll get better at figuring out how to use it yourself.

§20.7. More about questioning objects of native prepositions

Another question pattern. Here are some questions you learned about in Lecsyony Tseinyabchon:

|

Tu dets zubga Lia Len? |

“Who is Elena sitting behind?” |

|

Tu cwe zugwoo na? |

“Who are you standing next to?” |

|

Tu lo bcwatslo Chiecw? |

“Who did Chico hide from?” |

These follow the question word – preposition – verb – subject – rest of sentence pattern.

As you learned, these “who” questions can use both native and Spanish prepositions. With native prepositions, however, there’s another pattern, as in these questions:

|

Tu zubga Lia Len detsni? |

“Who is Elena sitting behind?” |

|

Tu zugwoo cweni na? |

“Who are you standing next to?” |

|

Tu bcwatslo Chiecw loni? |

“Who did Chico hide from?” |

In these questions, the question word comes at the beginning (once again), but the preposition comes after the subject, followed by –ni [nìi’], the same ending that is used in possessive sentences (Lecsyony Tsëda).

Here is the pattern for these questions. Remember that this pattern is used only with native prepositions:

| question word | verb | subject | preposition | -ni | rest of sentence |

|

Tu |

zubga |

Lia Len |

dets |

-ni? |

|

|

Tu |

zugwo |

-o |

cwe |

-ni |

na? |

|

Tu |

bcwatslo |

Chiecw |

lo |

-ni? |

Tarea Xon xte Lecsyony Galy.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Ingles. Then, if possible, use another question pattern to ask the same thing.

a. Tu lo zurëng?

b. Tu zub becw cweni?

c. Tu lo bcwa Lia Len email?

d. Tu dets zugwa Jwany?

e. Tu cwe zundi gyag?

f. Tu mna Lia Da loni?

g. Tu blia permisy loni?

h. Tu lo gwe Rony mach?

i. Tu quinyën muly loni?

j. Tu lo bgwe dizh xnanu?

“What” questions. The same alternative pattern is used to ask “what” questions like the following:

|

Xi mnayu loni na? |

“What did you (form.) see?” |

|

Xi bcwetslo Mazh loni? |

“What did Tomas hide from?” |

In Valley Zapotec, it’s generally not good to begin a question with Xi lo, so this pattern is the right one to use.

“What” questions with cali. When you are questioning a “what” object of a location preposition in Valley Zapotec, however, you use the word cali (not xi) in sentences like the following:

|

Cali lany yzubri liebr? |

“What are they going to put the book in?” |

|

Cali lo beb gues? |

“What is the pot on?” |

|

Cali lo bzub xnanu gues? |

“What did your mother put the pot on?” |

|

Cali dets natga becw? |

“What is the dog sleeping behind?” |

The pattern here is just the same – you start the question with the question word, followed by the preposition, the verb, the subject, and the rest of the sentence. What’s unusual is that you use cali “where”, although we would expect to use “what” in English.

Tarea Ga xte Lecsyony Galy.

Bcwa ni ca ni guet cuan Dizhsa. Don’t forget to use cali when you are questioning a “what” location object.

a. What is the doctor looking at?

b. Who is Elena and Ignacio standing in front of?

c. Who are you writing that letter to?

d. What did he eat the soup with?

e. Who is Pedro sitting next to?

f. What is the dog lying on?

g. What did Gloria see?

h. What is the cat running around?

i. Where are the cups?

j. What did you put the blal next to?

§20.8. Modifying phrases with native prepositions

You learned about modifying phrases like the following in Lecsyony Tseiny (15):

|

zhyap ni wbany |

“the girl who woke up” |

|

ra becw ni bdeidya Bed |

“the dogs that I gave Pedro” |

|

ra becw ni mnizh Bed naa |

“the dogs that Pedro gave me” |

|

mna ni cuzh danuan zhi |

“the woman who will call us tomorrow” |

|

mna ni cuzhën zhi |

“the woman we will call tomorrow” |

|

mniny ni btaz Mazh |

“the boy who hit Tomas”, “the boy who Tomas hit” |

As you know, these include a modified noun phrase followed by ni — verb — rest of sentence. The same pattern is used whether the modified noun phrase is the subject or the object of the verb following ni.

A different pattern is used, however, when the modified noun phrase is the object of a native preposition within the modifying phrase. Here are some examples:.

|

gyizhily ni natga becw detsni |

“the chair that the dog is lying in back of” |

|

ra zhyap ni bcwatslon loni |

“the girls that we hid from” |

|

doctor ni zugwoo cweni |

“the doctor that you are standing next to” |

|

buny ni bgue xtada loni |

“the man that my father cussed out” |

|

museu ni mnaa loni |

“the museum that I saw” |

These phrases follow the pattern below:

| noun phrase | ni | verb | subject | preposition | -ni |

|

gyizhily |

ni |

natga |

becw |

dets |

-ni |

|

ra zhyap |

ni |

bcwatslo |

-n |

lo |

-ni |

|

doctor |

ni |

zugwo |

-o |

cwe |

-ni |

|

buny |

ni |

bgue |

xtada |

lo |

-ni |

|

museu |

ni |

mna |

-a |

lo |

-ni |

In these modifying phrases, the preposition always comes at the end, followed by the –ni [nìi’] ending you learned about in Lecsyony Tseiny (15) (the same –ni used in the question pattern described in section §20.7). These modifying phrases begin and end with ni – the modifying ni [nih] and the ending –ni [nìi’] – but the two ni‘s are pronounced differently.

For now, don’t try to use modifying phrases with Spanish prepositions.

Tarea Tsë xte Lecsyony Galy.

Part Teiby. Make up Zapotec sentences that contain modifying phrases for objects of the following native prepositions. Then translate your sentences into English.

a. lo

b. cwe

c. dets

d. guecy

e. lany

f. ni

g. zha

h. lad

i. lai

j. gagyeita

Part Tyop. Read one of your English sentences aloud to a partner and have him or her translate it into Zapotec. Compare that translation with your original Zapotec sentence. Are they identical? There may be more than one way to express the English sentences in Zapotec!

The item you are using to help specify the location of the SUBJECT in a locational SENTENCE. The reference item is the same as the PREPOSITIONAL OBJECT. See also CROSS REFERENCE.